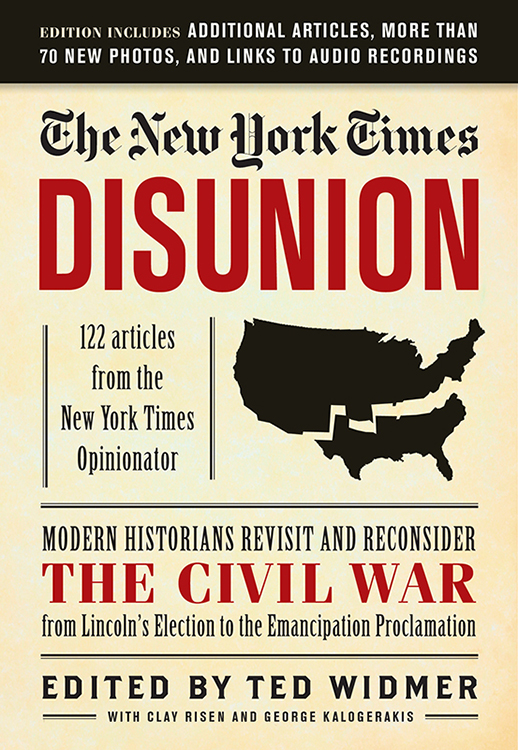

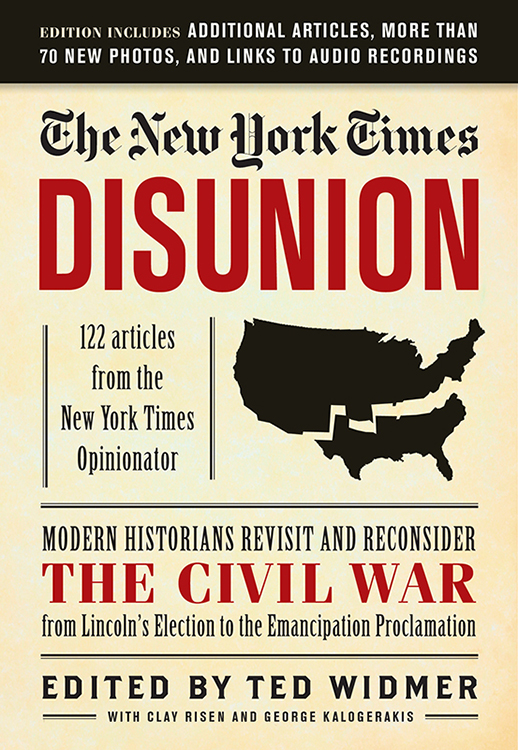

DISUNION

122 articles from The New York Times Opinionator

MODERN HISTORIANS REVIST AND RECONSIDER THE CIVIL WAR FROM LINCOLNS ELECTION TO THE EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION

EDITED BY TED WIDMER

WITH CLAY RISEN AND GEORGE KALOGERAKIS

Copyright 2013 The New York Times

All rights reserved. No part of this book, either text or illustration, may be used or reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the publisher.

Published by

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, Inc.

151 West 19th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by

Workman Publishing Company

225 Varick Street

New York, NY 10014

All images courtesy of The Library of Congress except the following:

Chicago Historical Society: p.

Daniel Borris: p.

New York Public Library: p.

The Museum of the Confederacy Richmond, Virginia Photography by Katherine Wetzel: p.

National Archive: p.

U.S. Games Systems: p.

Cover Design by Liz Driesbach

ISBN: 978-1-57912-928-6

eISBN: 978-1-60376-329-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

SECESSION

Chapter 2

THE WAR BEGINS

Chapter 3

BULL RUN

Chapter 4

1862

Chapter 5

THE WAR EXPANDS

Chapter 6

TOWARD EMANCIPATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Disunion began with Jamie Malanowski, who brought the kernel of the idea for the series to The New York Times Op-Ed staff in early 2010. For that, and for the many articles he later wrote for the series, some of which appear in this volume, we cannot thank him enough. Our gratitude goes as well to David Shipley, the Op-Ed editor who gave us the green light to proceed, and to his successor, Trish Hall, for continuing to back us. Behind and above all of this has been Andy Rosenthal, the Editorial Page editor and not-so-secret Civil War buff; without his support, none of this would have happened.

Though it is the writers names that appear on the articles, and our names on the cover of the book, much of the hard work in producing the Disunion series was performed by our Web teamSnigdha Koirala, Whitney Dangerfield and Kari Haskellour copy editorsJohn Guida, Kristie McClain and Roberta Zeffand our indefatigable accounts payable experts, Inell Willis and Natalie Shutler.

Finally, our thanks to Alex Ward, who helped take this book from a vague idea to a concrete plan, and the folks at Black Dog and LeventhalJ.P. Leventhal, Lisa Tenaglia and Stephanie Sorensenfor taking that plan and turning it into the beautiful tome you now hold in your hands.

INTRODUCTION

The Question of Disunion

BY TED WIDMER

But what can I say of that prompt and splendid wrestling with secession slavery, the archenemy personified, the instant he unmistakably showed his face? The volcanic upheaval of the nation, after that firing on the flag at Charleston, proved for certain something which had been previously in great doubt, and at once substantially settled the question of disunion.

Walt Whitman, Specimen Days

It is not easy to find a new way to write about a subject as well-reconnoitered as the Civil War. But 2013 seems a particularly appropriate year to take stock of our national epic. Historic anniversaries can pile up on themselves, and it requires concentration to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Gettysburg and the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington at the same time. Yet they are part of the same broad story, a rhyme that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. appreciated, as he used Lincolns temple to preach to the nation about the unfinished business of the Civil War. That business remains unfinished. For despite the peace that came, finally, at Appomattox, the Civil War remains a ghostly presence in American life. It will never vanish, as long as its principal monument, the United States of America, survives. Of course, the armies laid down their arms, and the soldiers came home to build new lives. Some tried desperately to forget the war. Then, inevitably, the prodigious act of remembrance began. Politicians waived their bloody shirts, generals wrote their memoirs, and, ever-dutiful, the veterans themselves reunited, on both sides, well into the 20th century. They decorated graves, they listened to speeches, sometimes they re-assembled on those original battlefields.

A century ago, in 1913, what was probably the most extraordinary Civil War reenactment of all took place at Gettysburg, played out by the former soldiers themselves, 53,407 of whom showed up, roughly a third of the number who had originally fought there. They were the same people, in the same place, but the Civil War had changed considerably since they last met there. A new Southern president, Woodrow Wilson, called it a forgotten quarrel, when it was nothing of the sort. But reawakening the bitterness of the conflict was nowhere near the agenda in 1913, and the majority of speakers that day preferred to remember how, rather than why, they had fought.

Each generation reenacts the Civil War in its own way. Even after the demise of the warriors (the last known veteran, Albert Woolson, died in 1956), it has never lost its power to fascinate. Todays re-enactors are so numerous that one wonders if their swampy battlefields are, in fact, spawning grounds. The Union lives on, in all of the ways that its adherents hoped, and more than a few that they could not have anticipated. Nor is the Lost Cause lostits acolytes populate State Houses and Southern rock songs, and even in Northern shrines like Gettysburg, Confederate memorabilia vastly outsells the less romantic souvenirs of the side that actually prevailed. On election night in November 2012, the map of red and blue states bore an uncomfortable similarity to a map of November 1862, an anniversary moment that no one had quite intended.

More than merely relevant, the Civil War remains essential. Each year, millions of students encounter it in the middle of year-long surveys of American history, halfway between the Revolution and the Atomic Age, when it interrupts our mostly happy national narrative with an explosive bang, just before the end of the fall semester. But its centrality stems from more than its timing. For the Civil War determined an enormous amount of the history that ensued, from the rise of mechanized conflict, so tragically a part of the 20th century, to the spread of multi-racial democracies, a happier chapter in recent history. It also permanently redefined the relationship between American citizens and their government. Ralph Waldo Emerson got it right when he said, We are undergoing a huge Revolution. What Lincoln called a new birth of freedom often felt like a straitjacket to those who opposed it, and their legacy is still felt, in the many forms of opposition to the federal writ that we witness on a daily basis. But the important fact with Lincoln is not simply that he wrote well; it is that he won. His fuller vision for the United States triumphed, with ramifications for nearly every walk of American life.

Superlatives come quickly in any discussion of the war. It was our most lethal conflict, by far, and its list of casualties continues to rise, as our means of counting improves. The Battle of Gettysburg killed more Americans than the recent fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. Historian and Harvard president Drew Gilpin Faust has reminded us that our dead in the Civil War exceeded those of the Korean War, the two world wars, the Spanish American War, the Mexican War, the War of 1812 and the American Revolution combined. Yet out of those terrible statistics, our greatest president emerged. Abraham Lincoln has never strayed far from the popular imagination, and in the wake of the 2012 film Lincoln, his position as our most beloved president is secure for some time to come. Writing instructors like to say keep your hero in trouble, and Lincoln was true to that injunction, frustrating generals, disappointing Senators, changing his stance on emancipation, appearing crude and indecisive to many, and nearly falling short in his bid for reelection. The worldwide adulation that he now commands never seemed possible, let alone likely, during much of his presidency. As he said, the Almighty has his own purposes.

Next page