Graham Robb

THE DISCOVERY OF

FRANCE

PICADOR

For Margaret

List of Illustrations

S ECTION O NE

S ECTION T WO

Itinerary

T EN YEARS AGO , I began to explore the country on which I was supposed to be an authority. For some time, it had been obvious that the France whose literature and history I taught and studied was just a fraction of the vast land I had seen on holidays, research trips and adventures. My professional knowledge of the country reflected the metropolitan view of writers like Balzac and Baudelaire, for whom the outer boulevards of Paris marked the edge of the civilized world. My accidental experience was slightly broader. I had lived in a small town in Provence and a hamlet in Brittany next door to people whose first language was not French but Provenal or Breton, and I first became superficially fluent in French, while working in a garage in a Paris suburb, thanks to an Algerian Berber from the mountains of Kabylie. Without him, the Parisian dialect of the foreman would have been completely incomprehensible.

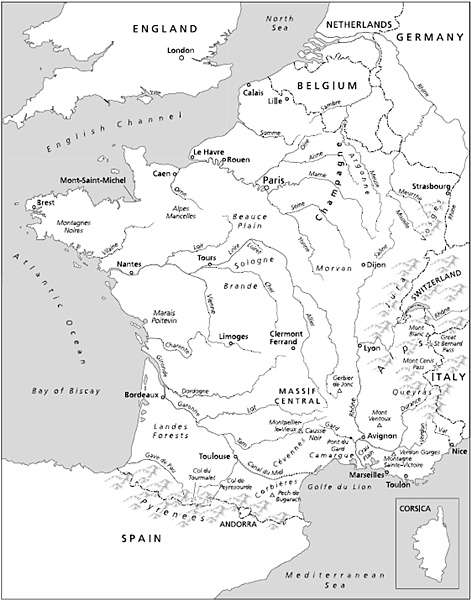

In the periods of history where I made my intellectual home, the gap between knowledge and experience was even wider. There was the familiar France of monarchy and republic, pieced together from medieval provinces, reorganized by the Revolution and Napoleon, and modernized by railways, industry and war. But there was also a France in which, just over a hundred years ago, French was a foreign language to the majority of the population. It was a country that had still not been accurately mapped in its entirety. A little further back in time, sober accounts described a land of ancient tribal divisions, prehistoric communication networks and pre-Christian beliefs. Historians and anthropologists had referred to this country, without irony, as Gaul and quoted Julius Caesar as a useful source of information on the inhabitants of the uncharted interior.

I owed my first real inklings of this other France to a rediscovery of the miraculous machine that opened up the country to millions of people at the end of the nineteenth century. Once or twice a year, I travelled through France with the dedicatee of this book at the speed of a nineteenth-century stagecoach. Cycling not only makes it possible to conduct exhaustive research into local produce, it also creates an enormous appetite for information. Certain configurations of field, road, weather and smell imprint themselves on the cycling brain with inexplicable clarity and return sometimes years later to pose their nebulous questions. A bicycle unrolls a 360-degree panorama of the land, allows the rider to register its gradual changes in gear ratios and muscle tension, and makes it hard to miss a single inch of it, from the tyre-lacerating suburbs of Paris to the Mistral-blasted plains of Provence. The itinerary of a cyclist recreates, as if by chance, much older journeys: transhumance trails, Gallo-Roman trade routes, pilgrim paths, river confluences that have disappeared in industrial wasteland, valleys and ridge roads that used to be busy with pedlars and migrants. Cycling also makes conversation easy and inevitable with children, nomads, people who are lost, local amateur historians and, of course, dogs, whose behaviour collectively characterizes the outlook of certain regions as clearly as human behaviour once did.

Each journey became a complex puzzle in four dimensions. I wanted to know what I was missing and what I would have seen a century or two before. At first, the solution seemed to be to carry a miniaturized library of modern histories, ancient guidebooks and travellers accounts, printed on thin paper in a tiny typeface. For example, a set of the reports written by the Prefects who were sent out by Napoleon after the Revolution to chart and describe the unknown provinces could be made to weigh less than a spare innertube. It soon became apparent, however, that the terra incognita extended much further than I had realized and that far more time would have to be devoted to the more physically demanding task of sedentary research.

This book is the result of fourteen thousand miles in the saddle and four years in the library. It describes the lives of the inhabitants of France wherever possible, through their own eyes and the exploration and colonization of their land by foreigners and natives, from the late seventeenth century to the early twentieth. It follows a roughly chronological route, from the end of the reign of Louis XIV to the outbreak of the First World War, with occasional detours through pre-Roman Gaul and present-day France.

Part One describes the populations of France, their languages, beliefs and daily lives, their travels and discoveries, and the other creatures with whom they shared the land. In Part Two, the land is mapped, colonized by rulers and tourists, refashioned politically and physically, and turned into a modern state. The difference between the two parts, broadly speaking, is the difference between ethnology and history: the world that was always the same and the world that was always changing. I have tried to give a sense of the orrery of disparate, concurrent spheres, to show a land in which mule trains coincided with railway trains, and where witches and explorers were still gainfully employed when Gustave Eiffel was changing the skyline of Paris. Readers who are better acquainted with the direct route of political history may wish to take their bearings from the list of events at the back of the book.

This was supposed to be the historical guidebook I wanted to read when setting out to discover France, a book in which the inhabitants were not airlifted from the land for statistical processing, in which France and the French would mean something more than Paris and a few powerful individuals, and in which the past was not a refuge from the present but a means of understanding and enjoying it. It can be read as a social and geographical history, as a collection of tales and tableaux, or as a complement to a guidebook. It offers a sample itinerary, not a definitive account. Each chapter could easily have become a separate volume, but the book is already too large to justify its inclusion in the panniers. It was an adventure to write and I hope it shows how much remains to be discovered.

PART ONE

The Undiscovered Continent

O NE SUMMER IN THE EARLY 1740s, on the last day of his life, a young man from Paris became the first modern cartographer to see the mountain called Le Gerbier de Jonc. This weird volcanic cone juts out of an empty landscape of pastures and ravines, blasted by a freezing wind called the burle. Three hundred and fifty miles south of Paris, at a point on the map diametrically opposed to the capital, it stands on the watershed that divides the Atlantic from the Mediterranean. On its western slope, at a wooden trough where animals once came to drink, the river Loire begins its six-hundred-and- forty-mile journey, flowing north then west in a wide arc through the mudflats of Touraine to the borders of Brittany and the Atlantic Ocean. Thirty miles to the east, the busy river Rhne carried passengers and cargo down to the Mediterranean ports, but it would have taken more than three days to reach it across a sparsely populated chaos of ancient lava-flows and gorges.

If the traveller had scaled the peak of phonolithic rock so called because of the xylophonic sound the stones make as they slide away under a climbers feet he would have seen a magnificent panorama: to the east, the long white curtain of the Alps, from the Mont Blanc massif to the bulk of Mont Ventoux looking down over the plains of Provence; to the north, the wooded ridges of the Forez and the mists descending from the Jura to the plains beyond Lyon; to the west, the wild Cvennes, the Cantal plateau and the whole volcanic range of the upper Auvergne. It was a geometers dream almost one-thirteenth of the land surface of France spread out like a map.

Next page