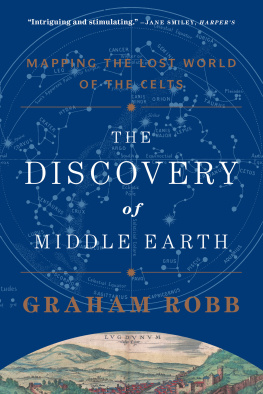

Graham Robb - The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe

Here you can read online Graham Robb - The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Pan Macmillan UK, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe

- Author:

- Publisher:Pan Macmillan UK

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For my sister Alison

The idea that became this book arrived one evening like an unwanted visitor. It clearly expected to stay for a long time, and I knew that its presence in my home would be extremely compromising. Treasure maps and secret paths belong to childhood. An adult scholar who sees an undiscovered ancient world reveal itself, complete with charts, instruction manual and guidebook, is bound to question the functioning of his mental equipment.

I was living at the time in a thatched cottage on a hill to the west of Oxford, in the land of Matthew Arnolds Scholar Gypsy. It was the setting of a childs fantasy world, the kind of place where historical secrets seem to offer themselves up like apples from a prolific, untended tree. In the garden, along with the remains of Victorian picnics and the luminous, degraded waste of the twentieth century, there were burnt flints, pieces of smelted metal and crudely fired roof-tile. Under the tangle of a spindle tree, I found a small Iron Age brooch with the corroded remains of its fastening pin and a pattern of three concentric circles. The farmer who lived next door showed me cardboard boxes full of quern stones used for grinding, Samian ware and Roman coins unearthed by his plough.

Though no book mentions it, this quiet place had once been a busy junction. Along one side of the garden, a bridleway was the end of an ancient straet that followed the limestone escarpment above the Thames and led to the Berkshire Downs and the Iron Age hill figure known as the Uffington White Horse. On the other side, an unpaved road climbed from a crossing of the Thames called Bablock Hythe, where there is now neither a bridge nor a ford. For many centuries, long before there was a place called Oxford, cattle and sheep had been driven up from the river to the point where the two roads met and broadened into a green with a spring and a pond. The contours of this ancestor of Cumnor village, which lies a twelve-minute walk from the later, medieval centre near the church, were masked by the more recent alignments of garden hedges and parking bays, but it was still possible to make out the form of the earlier village from an upstairs window. These patterns of settlement are too old to appear in documents. An abrupt bank of earth, and the remnant of a circular arrangement that gives the modern road a dangerous curve, are the probable vestiges of an Iron Age hill fort that overlooked the prehistoric settlement on the floodplain of the Thames at Farmoor.

In these conditions, it would not have been surprising if some chronic state of historical hallucination had taken hold. The irresistible visitor in the upstairs room took the form of a diagonal line on a map of western Europe, printed out on two large sheets of paper. I had been planning a cycling expedition along the Via Heraklea, the fabled route of Hercules from the ends of the earth the Sacred Promontory at the south-western tip of the Iberian Peninsula across the Pyrenees and the plains of Provence towards the white curtain of the Alps (fig. 1). The heros journey, with a herd of stolen cattle, is the legendary trace of one of the oldest routes in the Western world. For much of its course, it exists only as an abstraction, an ideal trajectory joining various sites that were associated with Hercules. Where it skirts the Mediterranean in southern France, on certain stretches it turns into a track, sometimes following the trails of transhumant animals, sometimes materialized as the Roman Via Domitia and the modern A9 autoroute. These practical, secular routes run up the eastern coast of Spain, turn north-east in France, and eventually wander off towards Italy. But in its original, mythic incarnation, the Via Heraklea marches in a straight line like the son of a god for whom a mountain was a paltry obstacle.

Two things struck me about this transcontinental diagonal. First, if the surviving sections are projected in both directions, the Heraklean Way follows the same east-north-easterly bearing for a thousand miles, and arrives, precisely, at the Alpine pass of Montgenvre, which the Celtsis the pass that Hercules is supposed to have created by smashing his way through the rock. It was as though, when he set off from the Sacred Promontory, he had been carrying some ancient positioning device which told him that he would cross the Alps at that exact point.

The second glimmer of something remarkable was the familiar appearance of the trajectory on the printout. Many ancient cultures including the Celts, the Etruscans and, occasionally, the Romans angled their temples, tombs and streets so that they either faced or stood in a geometrical relationship to the rising sun of the solstice. This is one of the two times of the year (around 21 June and 21 December) when the sun rises and sets in almost exactly the same place several days in a row. I consulted the online oracle of astronomical data: two thousand years ago, at a Mediterranean latitude, the trajectory of the Via Heraklea was the angle of the rising sun at the summer solstice or, if the observer were facing the other way, of the setting sun at the winter solstice.

This cosmic coincidence has remained entirely undetected. Perhaps its grandeur renders it effectively invisible. Even the least sceptical historian would doubt its existence. Yet it led to so many other verifiable discoveries that it seemed at times to have a mind of its own, a mechanism from another world, accidentally reactivated. The journeys it entailed took several years, but it became apparent within the first few months that the solstice path had been deliberately created. Druids and Druidesses the priests or scientists of the Celts standing anywhere on that ancient path, knew that when they looked along it to the west, they were looking towards the ends of the earth, beyond which there was nothing but the monster-haunted ocean and the land of the dead. In the other direction, they were facing the Alps and the Matrona Pass through which the sun returned to the world of the living.

Gradually, a third coincidence added itself to the picture. A few years before, while researching The Discovery of France, I had read about an enigmatic name Mediolanum which the ancient Celts had given to about sixty locations between Britain and the Black Sea. It meant something like sanctuary or sacred enclosure of the centre or middle. The word Mediolanum is thought to have been related to a notion that is also found in other mythologies: the idea that our world is a Middle Earth whose sacred sites correspond to places in the upper and lower worlds. In Norse and Germanic mythology, the word is Midgard, from which J. R. R. Tolkien derived the name of the fictional universe of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.

In 1974, a professor of literature called Yves Vad suggested that the Celts had organized these middle places according to a network, and that they had been arranged so that each one was equidistant from two others. The idea was taken up in 1994 by the Professor of Geography at the Sorbonne, Xavier de Planhol, who concluded that the network might briefly have served some practical or religious purpose but that it had been abandoned at an early stage. A random scattering of dots would produce similar results, and there were other problems with the idea, which will be mentioned later in this book. The name was intriguing all the same, especially since, after retracing the etymologies of all the Gaulish place names along the route, I found, on or near the line of the Heraklean Way, six places that had once been called Mediolanum.

From then on, coincidences cropped up with surprising frequency. A complex, beautiful pattern of lines emerged, based on solar alignments and elementary Euclidean geometry. I began to see, as though in some miraculously preserved document, the ancient birth of modern Europe. The places called Mediolanum had belonged to an early and comparatively chaotic stage of this mapping of a continent. Out of that fertile confusion of local systems, a vast network had evolved. The geography of the Western world had been organized into a grid of solstice lines, based on the original Via Heraklea, with precisely measured parallels and meridians determining the locations of temples, towns and battles. At an even later stage, in Gaul, and, more spectacularly, in the British Isles, some long-distance roads had been constructed as literal incarnations of the solstice lines. Knowledge of that grid had been lost in the bustle and belligerence of the Roman empire, and it often seemed as though that wonder of the ancient world had never existed at all.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe»

Look at similar books to The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Ancient Paths: Discovering the Lost Map of Celtic Europe and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.