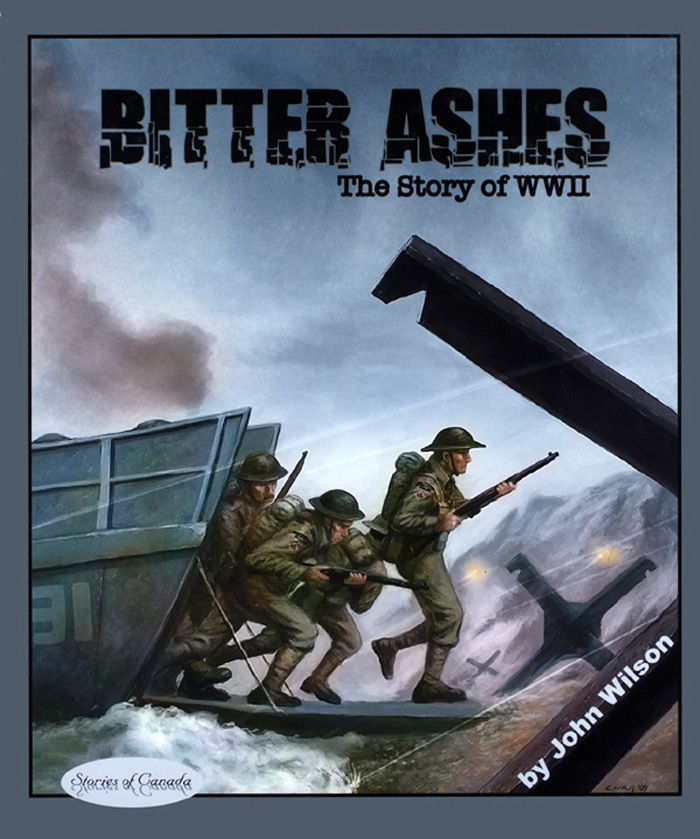

Bitter Ashes

The Story of WW II

by

John Wilson

Series editor: Allister Thompson

Napoleon Publishing

Text copyright 2009 John Wilson

Cover art by Christopher Chuckry

All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form

or by any means, digital, mechanical, photocopying or

otherwise, without the prior written consent of the publisher.

Napoleon Publishing

an imprint of Napoleon & Company

www.napoleonandcompany.com

Toronto Ontario Canada

Napoleon & Company acknowledges

the support of the Canada Council for the Arts

for our publishing program. We acknowledge the support of the

Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry

Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities.

Manufactured by Friesens Corporation in Altona, Canada

December 2009

13 12 11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Wilson, John (John Alexander), 1951

Bitter ashes : the story of WW II / John Wilson.

(Stories of Canada)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-894917-90-2

1. World War, 1939-1945--Juvenile literature. 2. World War, 1939-1945--Canada--Juvenile literature. 3. Canada--History-1939-1945--Juvenile literature. 4. World War, 1939-1945--Canada--Pictorial works--Juvenile Literature.

I. Title. II. Series: Stories of Canada (Toronto, Ont.)

D743.7.W54 2009 j940.5371

C2009-904778-0

For the children who died in the war

Children are not the people of tomorrow, but people today. They are entitled to be taken seriously. They have a right to be treated by adults with tenderness and respect, as equals. They should be allowed to grow into whoever they were meant to bethe unknown person inside each of them is the hope for the future.

-Janusz Korczak

(Korczak was in charge of an orphanage in the Warsaw ghetto. Refusing a chance to hide, he chose to accompany his children to the Treblinka death camp.)

Europe after the Treaty of Versailles in 1919

Contents

Guernica

The bombersangular triple-engined Junker 52s and sleek gull-winged Heinkel 111sswept over the hills from the north. For two-and-a-half hours on the afternoon of April 26, 1937, two dozen planes dropped forty tons of bombs on the undefended town of Guernica in Northern Spain.

Panicked refugees fled through the chaos of collapsing buildings. Shards of hot, jagged metal and fragments of walls and furniture flew everywhere. The air was filled with screams and the crackle of fires taking hold amidst the rubble.

The planners, pilots and bomb-aimers that day were mostly German, although they were fighting in the Spanish Civil War. They were there to help the Spanish army, which had revolted against the legal government in July, 1936, and they were there to practice for a much bigger war.

The attack shocked the world and inspired Pablo Picasso to paint one of arts great masterpieces, but it was a small scale tragedy compared with what would happen later to Barcelona, London, Berlin, Dresden, Tokyo and Hiroshima.

Guernica was a beginning. It was also a clear signal that wars were no longer just fought between armies on battlefields. In the coming war, civilian men, women and children would be front-line soldiers.

The Spanish Civil War was a national conflict with roots far back in Spanish history, but it was also a testing ground for new military technologies, tactics and political ideologies.

Thousands of individuals saw Spain as the beginning of something bigger and volunteered to help as soldiers, nurses and doctors. Among them were almost 1,600 Canadians who defied their own government to take a stand for what they believed in. Half of them never came home and, even today, none of them is commemorated on official war memorials in Canada or recognized in Remembrance Day services.

Pablo Picassos Guernica is reproduced as a wall mural in the modern town.

The Lost Peace

Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently.

-Rosa Luxemburg

On the night of January 15, 1919, Rosa Luxemburg, a leader of the new German Communist Party, was led from a police station in Berlin, beaten, shot and her body dumped in the Landwehr Canal.

At the end of WW I, Germanys army was defeated, its navy in revolt and its people starving. Civil war, like the one that was raging in Russia, seemed a certainty. But the German revolution failed. What was left of the army crushed it by killing the leaders such as Rosa Luxemburg, and a democratic government was established. Unfortunately, much of the bitterness of 1919 simmered beneath the surface and occasionally erupted in violence. Through it all, the average person struggled to survive as German money became worthless and communist workers and police battled each other in the streets.

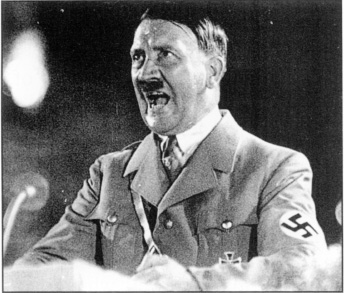

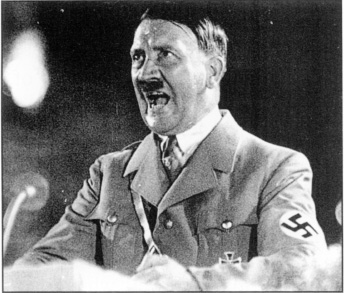

Adolf Hitler was famous for his impassioned, angry speeches. He wears the Nazi swastika symbol on his arm.

On July 29, 1921, an ex-corporal with a gift for speech-making became the leader of a small party composed largely of men who had fought against Luxemburg and the German Revolution. They called themselves the National Socialist German Workers Party and promised to bring law and order to Germany and make it a powerful country once more.

The National Socialist, or Nazi Party, was organized along military lines; its members wore brown uniforms and fought with, threatened and intimidated anyone who disagreed with them. By 1932 they were powerful enough to become the largest party in the German parliament. On January 30, 1933, their leader, Adolf Hitler, became German Chancellor. The following year, he declared himself Fhrer, or Leader, of Germany. On that day, the freedom to think differently in Germany disappeared, and Nazi ideology, under the direction of Hitler and his propaganda expert, Joseph Goebbels, became the law.

Italy had not been on the losing side in WW I, but it had suffered and, having only been a unified country since 1870, was as divided by internal tensions as Germany.

Like Hitler, Benito Mussolini was a veteran of WW I. After the war, Mussolini formed the National Fascist Party, which promised stability and a return to the glories of ancient Rome. In 1922 he led his party on a march on Rome and seized power. Shortly afterward, he declared himself supreme ruler, or II Duce.