But roll-call works a change. Name after name

Of comrades gone recaptures bit by bit

The battle for minds which thus can pause on it

With infinite compassion and no shame.

Thus do they focus sense diffused of grief

On the particular dead, and thus derive

From pity and envy mixed a childs relief

That they themselves incredibly survive.

Leonard Barnes: Youth at Arms

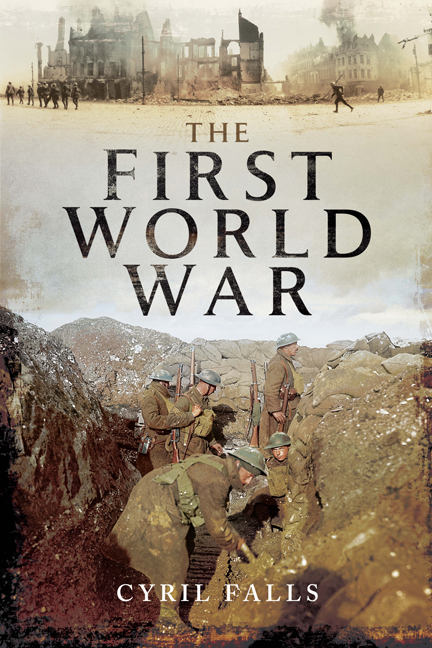

First published in Great Britain in 1960 by Longmans, Green and Co Ltd

Reprinted in this format in 2014 by

P EN & S WORD M ILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley, South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright The Estate of Cyril Falls, 1960, 2014

ISBN 978 1 47382 549 9

eISBN 9781473840997

The right of Cyril Falls to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The Publishers have made every effort to trace the author, his estate and his agent without success and they would be interested to hear from anyone who is able to provide them with this information.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

By CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Aviation, Atlas,

Family History, Fiction, Maritime, Military, Discovery, Politics, History,

Archaeology, Select, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Military Classics, Wharncliffe Transport, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press,

Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

To friends and companions, those growing old

and those to whom long life was denied

Contents

Maps

European and Near Eastern Theatres 19141918

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

All the photographs are reproduced by kind permission of the Imperial War Museum with the exception of numbers 9 and 10, courteously provided by the Militrwissenschaftliche Abteilung of the Austrian Ministry of Defence.

Preface

W HEN I had made good progress on this history I confided to a few friends what I was doing. They differed in age and interests, but all asked in virtually the same words: Whats your thesis? I was taken aback. I had not started with a thesis consciously in mind. I was, as I always had been, intensely interested in the subject. Having devoted to its study some twenty years of my life, not counting my modest participation in it, I could not doubt that I knew more about it than most. I hoped that a fair number of survivors would welcome a condensed account in what I trusted would be readable form, and that younger people would echo Southeys young Peterkin with:

Now tell us all about the war,

And what they fought each other for.

Before long I felt gratitude to those who had asked the question. They had helped me to clear my own mind. I began to realize that there had always been a thesis at the back of it. I wanted to show what the war had meant to my generation, so large a part of whichand so much of the best at thatlost their lives in it. I wanted to commemorate the spirit in which these men served and fought. The modern intellectual is inclined to look with impatience upon the ardour with which they went to war. To him it is obsolete. If so, I must be obsolete too. Looking back, the intensityand I dare add the purityof that spirit still moves me deeply. I speak particularly of the combatants, including leaders and staffs. In the circumstances of that war a large proportion of men in uniform might almost as well have been company directors, clerks, grocers assistants, or street cleaners at home, for the most part useful, but martial only in appearance and not always even that.

I find in the soldiers other virtues besides courage and self-sacrifice. Though their ardour became blunted, their comradeship never died. Then, though barbarity enters into all wars, they were in general remarkably free from this wickedness which soils the name of patriot. They were called to the colours as volunteers or conscripts on a scale greater than had ever been known; yet, though this was a war of nations in which the scum was swept along beside the finest elements and the far larger average, it was not where Britain was concerned a savage or cruel war. Its most abominable episodes, such as the Armenian massacres perpetrated by the Turks, do not match the cold cruelty of the Second World War.

Next I wanted to do all I could to demolish a myth as preposterous as it is widely believed. For the first time in the known history of war, we are told, the military art stood still in the greatest war up to date. Theoretically and historically this appears impossible. I believe reality reflects theory and history. The only grain of truth in the myth derives from the very fact that this was the greatest war: commanders were often baffled by its size and the masses engaged in it. Most of the belligerents, however, threw up leaders notable for skill and character, though Russia found none of the highest apart from Brusilov and Yudenich, and it is hard to rank the Italians Cadorna and Diaz as more than capable organizers. France, Germany, and Britain produced many. Joffre, Foch, Ptain, Franchet dEsprey, and Mangin; Falkenhayn, Ludendorff, Otto von Below, Gallwitz, and Hutier; Haig, Rawlinson, Plumer, Maude, and Allenbyall these were great figures. Near them stood more junior leaders of merit, several of whom would have risen in stature with bigger responsibilities. Take one on whom fortune unexpectedly smiled. Lord Cavan, when a corps commander on the Western Front, was known only as a sound general with the steadfast qualities often seen in British Guardsmen; as army commander in Italy under the Italian Commander-in-Chief, he revealed himself to be also an imaginative soldier and endowed with political flair and tact, masterly in dealings with allies. The American Pershing and Liggett, the Austrian Conrad von Htzendorf and Krauss, the Serbian Putnik and Mii, were outstanding figures. Of all, Haig and Pershing would have been the most difficult to replace in their roles.

I doubt whether naval leadership matched the best among the soldiers, except in the case of Hipper. To me he is the most attractive figure among the admirals, and his handling of his battle cruisers at Jutland bears the stamp of genius. Jellicoe, Beatty, Wemyss, Scheer, and von Reuter all possessed professional skill and were personalities in their different ways. The young air service was training leaders rather than producing them within the span of the war, and the figures who really stand out are Trenchard and John Salmond.

I have striven to find space for impressions on generalship, especially that of Haig, and given more to it than I would have but for the myopia of the English-speaking races where it was concerned. The Germans have not been equally myopic.

Another feature of my thesis has been my long-held belief that the role of the Austro-Hungarian Army has been underrated by Britons and Americans, largely through prejudiced German testimony. This view has been confirmed by recent reading.