Springer-Verlag London 2014

Jeffrey M. Weinberg and Mark Lebwohl (eds.) Advances in Psoriasis 10.1007/978-1-4471-4432-8_1

1. History of Psoriasis

Abstract

An understanding of disease overall and, skin disease in particular, has been a unique part of modern times. Previously those with psoriasis were often mislabeled, poorly regarded, and suffered as a consequence. Symptoms were often considered the disease itself; this lack of understanding made for difficulty in establishing psoriasis as a disease entity. The subsequent struggle to understand the pathogenesis of psoriasis limited the progress in its treatment. We review the path taken to enhance our understanding of this complex skin disease as well as the discovery of the varied treatments which initially were serendipitously indentified followed over the decades by ones based on scientific knowledge. The further understanding of this disease has allowed for continued progress and specificity of these modalities as well as the identification of the associated co-morbid conditions. The history of psoriasis, therefore requires an appreciation of how the understanding of this disease has progressed over time in parallel with its evolving treatment options.

Disclosures

John B. Cameron Ph.D.-none

Abby S. Van Voorhees, MD-She has served as a consultant for the following companies: Amgen, Novartis, Pfizer, Celgene, Abrie, Genentech, Warner Chilcott, Janssen, Leo. She has worked as an investigator for the following companies: Amgen, Abbott. She has been a speaker for the following companies: Amgen, Abbott, Janssen.

History of Disease

An understanding of disease overall and, skin disease in particular, has been a unique part of modern times. Previously those with psoriasis were often mislabeled, poorly regarded, and suffered as a consequence. Symptoms were often considered the disease itself, and consequent progress in treatment was limited by this lack of understanding of the disease and its cause. The history of psoriasis therefore requires an appreciation of how the understanding of disease has progressed over time and the often serendipitous findings of treatment options.

Pre-scientific societies often viewed disease as resulting from a violation of the sacred order, the malignant influence of magic or the breaking of a taboo. For example the entire thirteenth chapter of the Book of Leviticus concerns how the priests may determine if an outbreak on the skin is leprosy and the fourteenth chapter concerns which animals (lambs and birds) shall be sacrificed to purify the victim [].

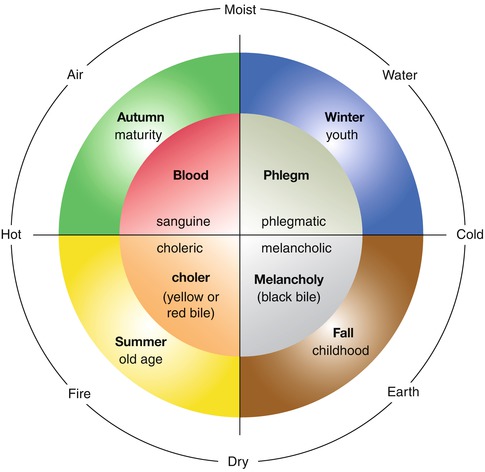

The first cultures that developed notions of rational science were China and Greece. Western medicine finds its roots in the Greek belief that disease results from natural causes, that in some way the balance or integrity of the body has been disrupted. Treatment, therefore, consisted in restoring that balance or integrity. Hippocrates may be the father of western medicine but the most influential founder was more likely Galen of Pergamon (130200 CE) To Galen the human body was a very complex organism made up not just of the four humors but also of gradations of dry and moist and hot and cool [).

Fig. 1.1

Diagram of humours, elements, qualities and seasons

Identification of Psoriasis as a Unique Disease

It is extremely difficult to tease out the history of psoriasis and its treatment in the ancient world because of confusion between psoriasis and many other diseases. Furthermore in the past the names assigned to diseases and symptoms were arbitrary and inconsistent. Identification of psoriasis in Egypt is especially difficult because of confusion between the disease and leprosy in later times []. However, since extensive examination of Egyptian mummies would indicate that leprosy was not present in Egypt before the common era, it is possible that psoriasis was mislabeled as leprosy.

We face similar problems of terminology in Greek medicine. The Corpus Hippocraticum contains precise descriptions and treatments for many recognizable diseases of the skin []. Again, it is likely that much of what was referred to as leprosy was in fact psoriasis. The appearance of true leprosy early in the common era compounded the confusion and sometimes lead to harsh treatments for those with psoriasis since lepers were often isolated and forbidden to associate with non-leprosy population.

The first indisputable reference to psoriasis comes from the fifth and sixth books of Aulus Cornelius Celsus, De Re Medica (circa 25 BCE-circa 50 CE) a Roman who compiled an extensive list of diseases and treatment for use by estate owners []. Celsus did not use the term psoriasis but rather describes it under the heading impetigo.

After the collapse of Roman culture, the practice of scientific medicine in the west disappeared and only returned as a part of the Renaissance. Geronimo Mercurialis penned a summary of what was known of skin diseases in 1572 []. Mercuralis lumped psoriasis in with other diseases as Lepra. He mentions several treatments including wolf dung rubbed in with vinegar, blood of a mountain goat as well as the rubbing of psoriasis with cantharides.

Robert Willan (17571812) set out clear and uniform nomenclature of skin diseases in 1809. However, his terminology unfortunately perpetuated some confusion in that he called psoriasis lepra vulgaris []. In 1898 Munro described the micro abscesses of psoriasis now called Munros abscesses. With the addition in the early twentieth century of Leo van Zumbusch of generalized pustular psoriasis and Waranoffs description of the pale halo now called woranoff ring, accurate diagnosis of psoriasis became commonplace.

History of the Treatment of Psoriasis

The history of the treatment of psoriasis has been largely driven by serendipitous findings until the last decade. The late 1700s and 1800s included treatments such as arsenic, chrysarobin and ammoniated mercury. Anthralin and tar came into widespread use in the first half of the twentieth century. Starting in the 1950s topical steroids were developed followed by the arrival of methotrexate, retinoids, and immunosuppressive medications in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s respectively. An enhanced understanding of the pathogenesis of psoriasis has allowed for more targeted drug development in the twenty-first century. Our therapeutic armamentarium now includes medications known as the biologics which target various aspects of the immune system allowing for its regulation.

Arsenic, Ammoniated Mercury and Chrysarobin

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries three topical agents are known to have been used in the treatment of psoriasis. While probably first developed by the ancient Greeks, arsenic solution was first utilized in dermatology in 1786 []. The use of this mercury in the topical treatment of psoriasis has been attributed to Dr. Fox in 1880. It was championed as well by Duhring. The use of both of these topical agents continued until the 1950s and 1960s when concerns about their possible toxicity risks and accidental poisonings caused their prohibition. The third topical agent that was identified was chrysarobin. A serendipitous finding, it was noted to be of benefit in the treatment of psoriasis by Balmonno Squire in 1876. His patient, who was using Goa powder to treat a presumed fungal infection, was noted to have improvement of his psoriasis. Kaposi in 1878 also published his experience with this topical approach to psoriasis.