To my parents,

Hollis and Annette Holland

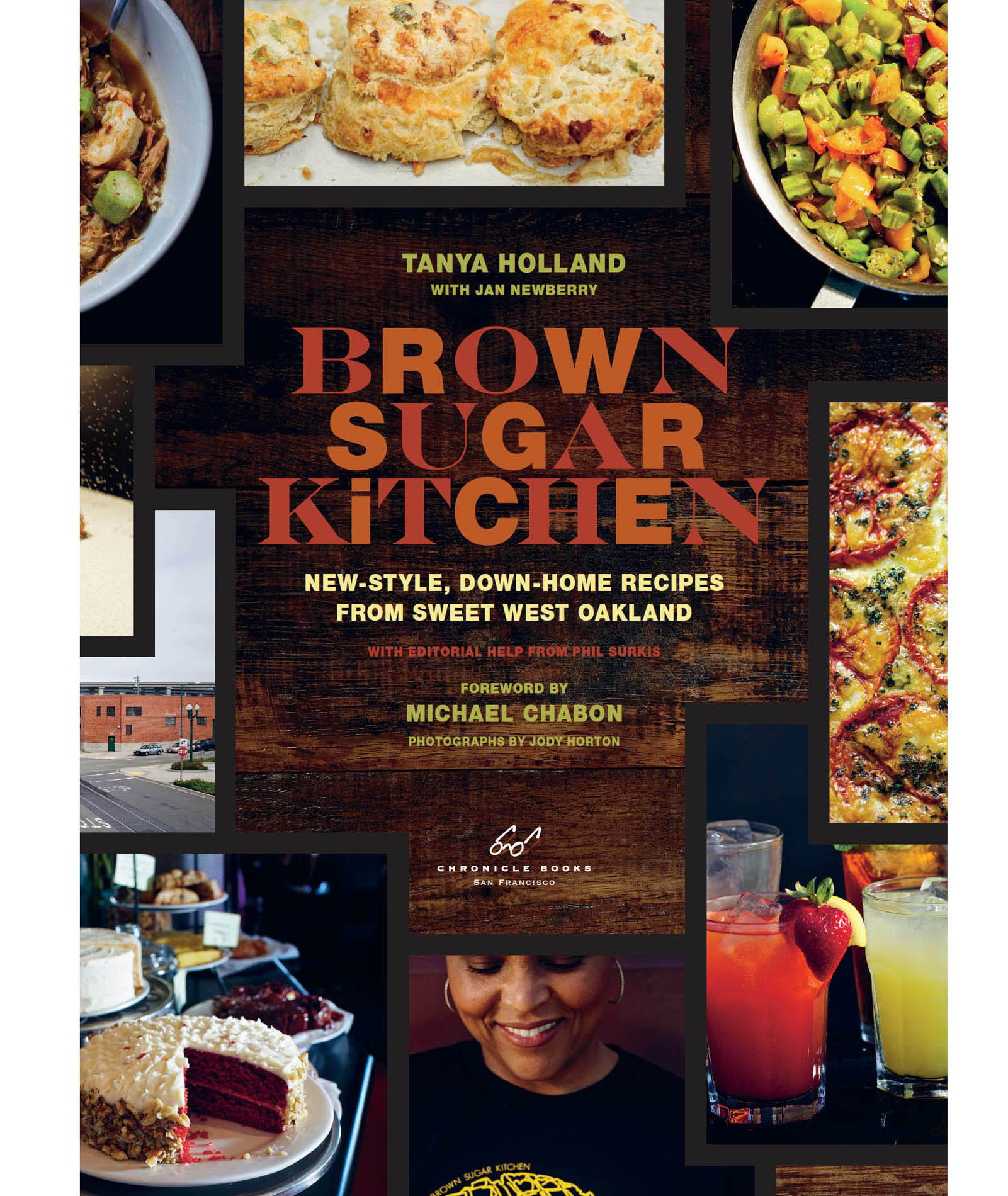

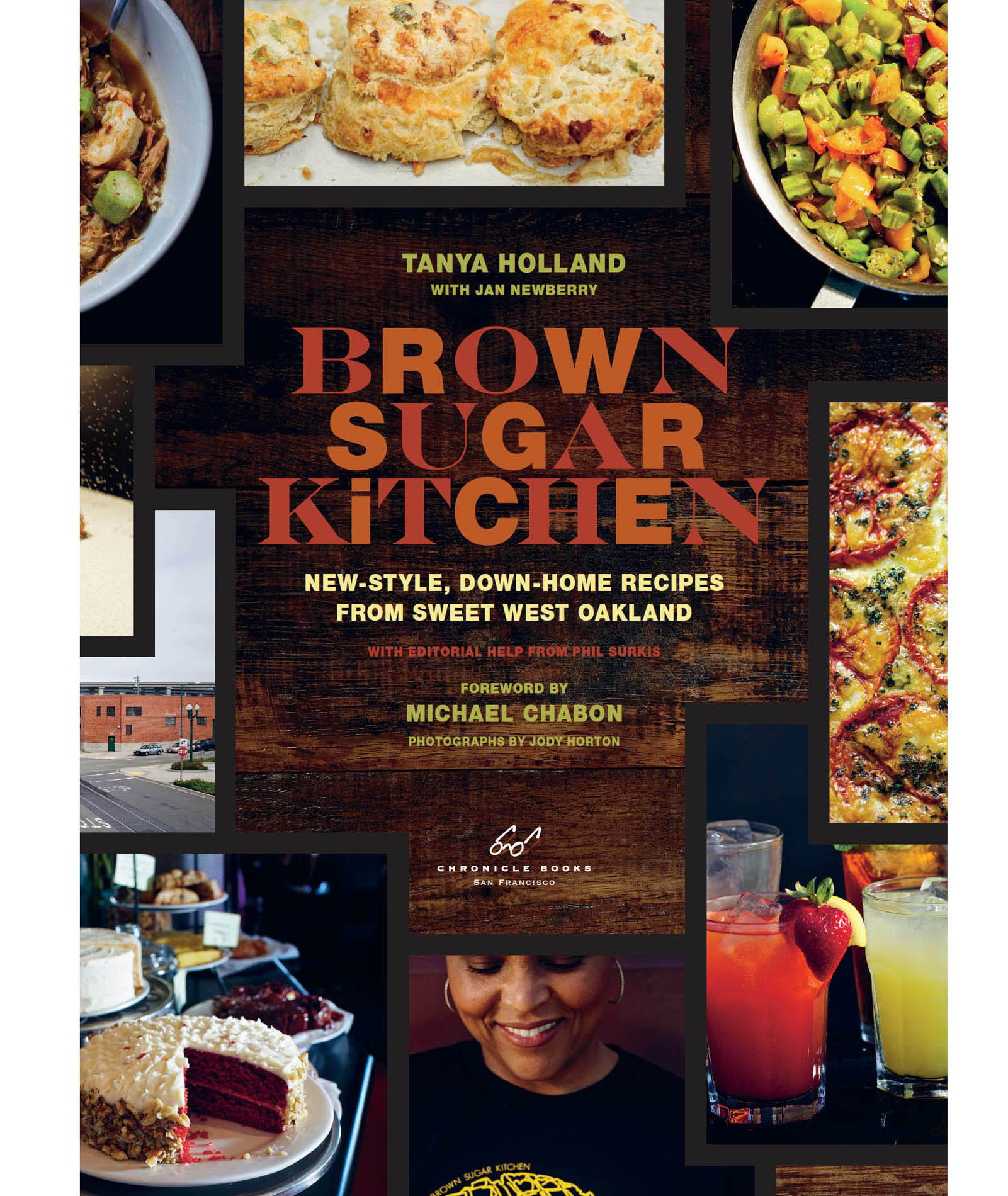

Text copyright 2014 by Tanya Holland.

Photographs copyright 2014 by Jody Horton.

Photographs on copyright 2014 by Lisa Keating.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 978-1-4521-2234-2 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-4521-3063-7 (epub, mobi)

Designed by Alice Chau

Typesetting by Howie Severson

Prop styling by Kate LeSueur. Many thanks to Heath Ceramics for the dishes on .

Food styling by Kate LeSueur and Tanya Holland

Angostura aromatic bitters is a registered trademark of Angostura Limited.

Burlesque bitters is a registered trademark of Bittermans Inc.

Buffalo Trace bourbon is a registered trademark of Buffalo Trace Distillery.

Dry Soda is a registered trademark of Dry SODA Co.

Four Roses Bourbon is a registered trademark of Four Roses Distillery LLC.

Goslings Black Seal Bermuda Rum is a registered trademark of Gosling Brothers, Ltd.

Gran Classico Bitter is a registered trademark of Tempus Fugit Spirits.

Heinz Chili Sauce is a registered trademark of H.J. Heinz Co.

Tabasco is a registered trademark of McIlhenny Company.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

FOREWORD

BY MICHAEL CHABON

Oaklandlike a swinging party, like an emergencyis happening. Oakland is always happening. From the moment of its founding, in the 1850s, by a nefarious confederation of squatters, opportunists, filibusterers, graft artists, boosters, visionary thieves and confidence men, Bump City has been happening. And yet, in all that time, Oakland has never quite happened. Or rather, Oakland never has happened. Oakland has never had its day. It has never gone soft, grown fat, rested on its laurels. It has never entirely gotten its act together, remembered to set its alarm clock, made it through to payday, waited for its cake to cool completely. There is a there there (Oakland coolly says Bite me to Gertrude Stein); but Oaklands not there yet.

Getting there, though. Oakland isalways, forevergetting there.

Oakland is like America, in that way. Oaklands like America in a lot of waysviolent and peace-loving, burdened by a calamitous racial history, factious and muddled, friendly and casual, rich in local genius and in natural beauty, poorly governed, sweet-natured, cold- eyed, out to lunch, out for blood, out for a good time. And, above all, promising. Every day, Oakland makes and breaks the American promise, a promise so central to the idea of America that we carry it around everywhere we go, in our wallets, jingling in our pockets. I mean, of course, E pluribus unum: Out of all the scattered sparks, one shining light. Its a utopian promise, and like all utopian promises, liable to breakage. But even if that promise can never truly be redeemed, it can beit must beendlessly renewed. And its the work that we put in, day after day, toward renewing the promise, not the promises fulfillment, that really matters.

Tanya Holland knows that. Every day, starting at 5:30 A.M ., she renews Oaklands promise at Brown Sugar Kitchen, a little hip-pocket utopia in the citys wild west end. Of all the many good restaurants, greasy-spoon to top-drawer, that make up a substantial share of the cultural wealth of Oakland, Tanyas Brown Sugar Kitchen most clearly, most faithfully, and most thrillingly embodies, one plate of chicken and waffles at a time, the ongoing, ever-renewed promise of the city she has come to love and, in a very real sense, to embody.

Drop by Brown Sugar Kitchen any day, for breakfast or lunch, and you will find people of all ages and stations, professing various brands of faith or doubt, tracing their ancestries to Africa and Europe, Asia and South America, to the Cherokee, Shawnee or Creek. You might very well find all those inheritances gathered around a single table, perhaps even in the genetic code of a single member of the waitstaff.

Diversity in the kitchen and dining room is hardly unusual in an Oakland restaurant, of coursethats one of the things to love about Oakland. Even in cities segregated far more determinedly than Oakland, Ive noticed that a popular soul-food restaurant will often feature the most integrated tables in townthats one of the things to love about soul food. Beans, rice and collards are a powerful force for transformation. But the crowds different at Brown Sugar Kitchen. More jumbled, the lines of race and class drawn more faintly than in Oaklands other restaurants, soul-food or otherwise. A more purposive clientele, I want to say, self-jumbled, everybody showing up with his or her own eraser to rub away at those lines a little more. One of the most beautiful things about human beings, in the midst of so much that is ugly, is the desire that takes hold of us, if only we can manage to leave our homes, our villages and our little worlds behind, for the companionship of people from Elsewhere. Make no mistake; people come to Brown Sugar Kitchen for the food. I believe that I could be hauled back from the gates of the Underworld by the prospect of a bowl of Tanyas shrimp and grits. But it was Oakland and not some other town, remember, that cradled the visions of the most high prophet Sly Stone, and to a greater extent than Ive found in other American cities, the Everyday People of Oakland are hip to the possibility that the point of the journey is neither the destination nor the journey itself but rather the coming to a crossroads, to a watering hole, to what my character Archy Stallings, in Telegraph Avenue, likes to call a caravansary. The point of the journey, to the everyday wanderer, is the feeling one gets on crossing the threshold of one of those magical places along the way, built on the borderline between here and there, where the stories and the homelands and the crooked routes of history come together in a slice of sweet potato pie.

Maybe the word Im looking for to describe the spirit that imbues the patrons and the principals of Brown Sugar Kitchen is something more like mindfulness. (An East Bay word if there ever was one.) As lovers of Oakland, Tanya and her husband, Phil Surkis, are mindful that the neighborhood where they chose to build their caravansary is the broken heart of Oakland, the place where all those industrious scoundrels who afterward lent their names to streets and civic buildings first conspired to defraud the Peralta family of their land. All the paths of ancestry and migration taken by Oaklands founding peoplesIndian, Spanish, Mexican, Anglo-, Asian-, and African-Americanare densely knotted in West Oakland, with its physical routes and roadways, its boulevards and streets. West Oakland is the great crossroads of the citys history, the stage and the scene of its starkest crimes and dramas, its most tragic comedies, from the founding land- grab to the glory of the Pullman strikes, from the apocalyptic destruction rained down by federal urban policy in the 60s to the collapse of the Great Beast of Urban Renewal, the Cypress Freeway, during the Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989. The Black Panthers, the Oakland Oaks, shipbuilders and railway workers, immigrant Jews and Portuguese, Okies and followers of the Great Migration, all came and went along Market and Cypress and West Street, as neighborhoods rose and fell, and Huey P. Newton got murdered, and the industrial demands of two world wars brought a measure of security and comfort, often for the first time, to people whose status had been marginal and precarious. Tanya and Phil were mindful, in choosing the site for their caravansary, that there could be no better place than along the Mandela Parkway, the enchanted road that grew up, gracious and wide and landscaped with greenery, in the gap that had once been the dark underbelly of the Cypress Freeway.

Next page