Table of Contents

Praise for Amish Grace

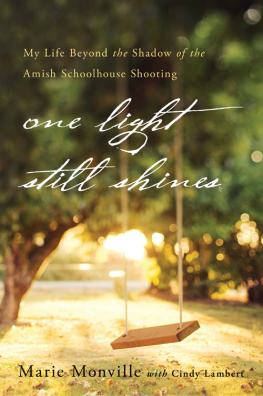

Amish Grace: How Forgiveness Transcended Tragedy is one of those rare books that inspires deep personal reflection while recounting a moment in history, telling a sociological story, and exploring theological issues. In the fall of 2006, following the murders of Amish school children by a deranged gunman, how did the Amish manage to forgive the murderer and extend grace to his family so quickly and authentically? Making it clear that the answer involves no quick fix but an integrated, disciplined pattern of lifea pattern altogether upstream to the flow of American culturethe authors invite us to ask not just how to forgive but how we should live. In our era of mass violence and the derangement from which it comes, no question could be more timely.

Parker J. Palmer, author of A Hidden Wholeness, Let Your Life Speak, and The Courage to Teach

Amish Grace tells a story of forgiveness informed by deep faith, rooted in a rich history, and practiced in real life. In an American society that often resorts to revenge, it is a powerful example of the better way taught by Jesus.

Jim Wallis, author of Gods Politics; president, Sojourners/Call to Renewal

An inside look at a series of events that showed the world what Christ-like forgiveness is all about... A story of the love of God lived out in the face of tragedy.

Tony Campolo, Eastern University

Amish Grace dissects the deep-rooted pattern of Amish forgiveness and grace that, after the Nickel Mines tragedy, caused the world to gasp.

Philip Yancey, author of Whats So Amazing About Grace?

Covers the subject in a superb way. It gave me a private tutorial in Amish culture and religion... on their unique view of life, death, and forgiveness.

Fred Luskin, author of Forgive for Good; director, Stanford Forgiveness Projects

A remarkable book about the good but imperfect Amish, who individually and collectively consistently try to live Jesus example of lovefor one another and for the enemy. Dr. Carol Rittner, R.S.M., Distinguished Professor of Holocaust & Genocide Studies, The Richard

Stockton College of New Jersey

A casebook on forgiveness valuable for ALL Christians.... drills beneath the theory to their practice and even deeper to the instructions of Jesus.

Dr. Julia Upton, R.S.M., Provost, St. Johns University

This is a very uplifting and enlightening book. It opens the door and allows us to peek at the hearts of Christian Amish believers who forgave horrid murders from the heart. And that forgiveness became a light on a hill that points to Jesus.

Everett L. Worthington Jr., professor of psychology, Virginia Commonwealth University

All author royalties from Amish Grace will be donated to the Mennonite Central Committee to benefit their ministries to children suffering because of poverty, war, and natural disaster.

For more information on the worldwide relief and service ministries of MCC, visit www.mcc.org.

PREFACE

Amish. School. Shooting. Never did we imagine that these three words would appear together. But the unimaginable turned real on October 2, 2006, when Charles Carl Roberts IV carried his guns and his rage into an Amish schoolhouse near Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania. Five schoolgirls died that day, and five others were seriously wounded. Turning a tranquil schoolhouse into a house of horror, Roberts shattered a reassuring American myththat the Old Order Amish remain isolated from the problems of the larger world.

The Amish rely less on that myth than do those who watch them from afar. In fact, their history reminds them that even the most determined efforts to remain separate from the world and its iniquities are not foolproof. The Nickel Mines Amish certainly didnt anticipate the horror of October 2. They were, however, uncommonly prepared to respond to it with graciousness, forbearance, and love. Indeed, the biggest surprise at Nickel Mines was not the intrusion of evil but the Amish response. The biggest surprise was Amish grace.

This book explains the Amish reaction to the Nickel Mines shooting, especially their forgiveness of the killer and their expressions of grace to his family. Given our longtime study of Amish life, we werent entirely surprised by the Amish response. At the same time, their actions raised a host of questions in our minds: What exactly did the Amish do in the aftermath of the tragedy? What did it mean to them to extend forgiveness? And what was the cultural soil that nourished this sort of response in a world where vengeance, not forgiveness, is so often the order of the day?

As we explore these questions, we introduce some aspects of Amish culture to show the connection between Amish life and Amish grace. This tie is important for two reasons. First, it clarifies that their extension of grace was neither calculated nor random. Rather, it emerged from who they were long before that awful October day. Second, embedding the Amish reaction in the context of their history and practice enables us to suggest more easily what lessons may apply to those of us outside Amish circles.

In the Appendix we provide details about some of the distinctive features of this community, but a few words of introduction here will help set the stage for our story. The Amish descend from the Anabaptists, a radical Christian movement that arose in Europe in 1525, shortly after Martin Luther launched the Protestant Reformation. Opponents of the young radicals called them Anabaptists, a derogatory nickname meaning rebaptizers, because they baptized one another as adults even though they had been baptized as infants in the state church. These radical reformers sought to create Christian communities marked by love for each other and love for their enemies, an ethic they based on the life and teaching of Jesus. Nearly two centuries later, in the 1690s, the Amish emerged as a distinct Anabaptist group in Switzerland and in the Alsatian region of present-day France.

The Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, are one of many Amish subgroups in North America. Most Amish groups are also known as Old Orders because they place a premium on maintaining old religious and social customs. Mennonites, who are religious cousins to the Amish, also trace their roots to the sixteenth-century Anabaptists. Many, but not all, of the Mennonite groups in the twenty-first century are more assimilated into mainstream culture and use more technology than the Amish.

Even though the occasion for this book is one we would like to erase from Lancaster County history, we believe it opens a window onto Amish faith. Buggies, beards, and bonnets are the distinctive markers of Amish life for most Americans. Although such images provide insights into Amish culture and the values they hold dear, Amish people are likely to say that they are simply trying to be obedient to Jesus Christ, who commanded his followers to do many peculiar things, such as love, bless, and forgive their enemies. This is not a picture of Amish life that can easily be reproduced on a postcard from Amish Country; in fact, it can be painted only in the grit and grime of daily life. Although it would be small comfort to the families who lost daughters that day, the picture of Amish life is much clearer now than it was before October 2006.