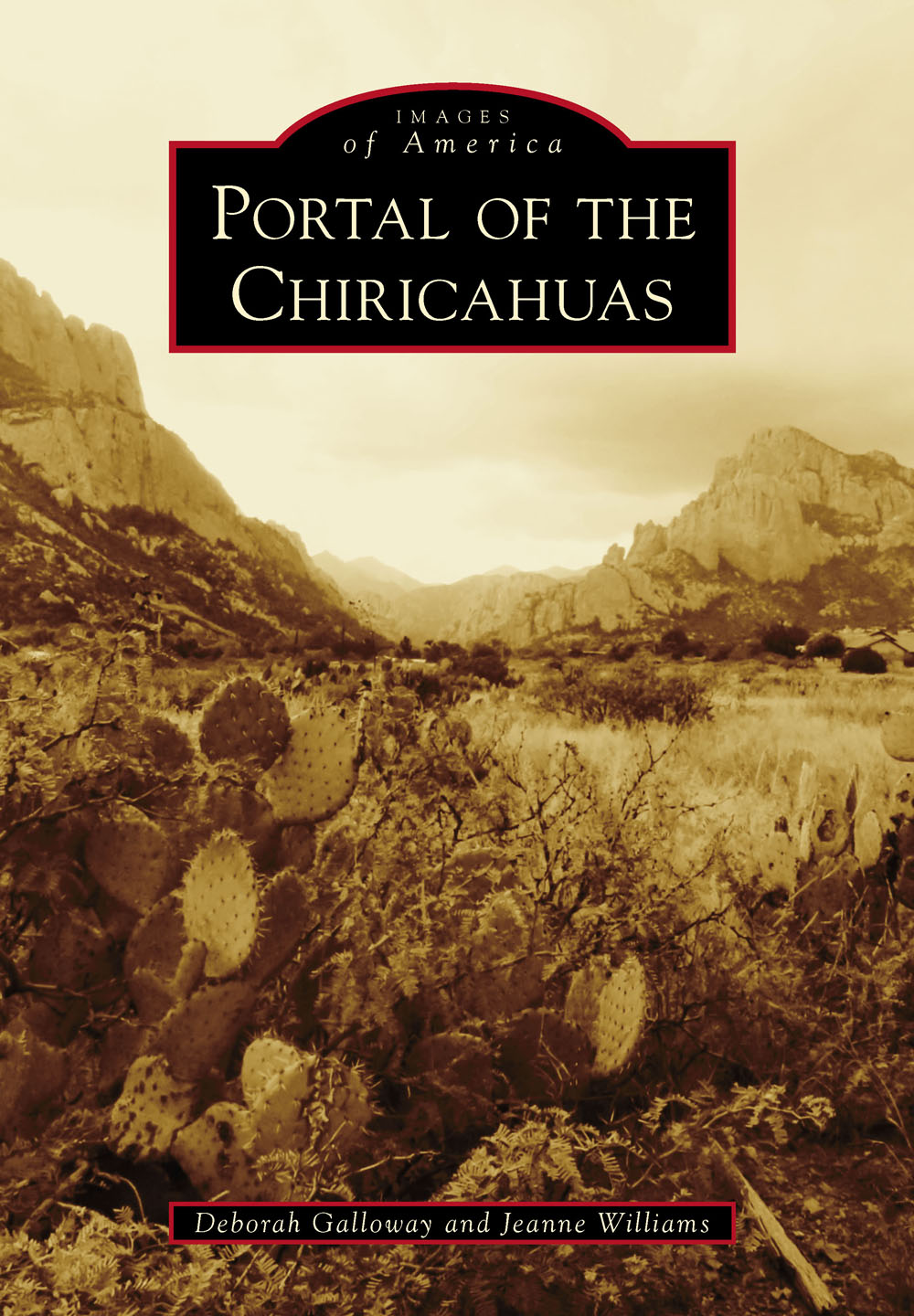

IMAGES

of America

PORTAL OF THE

CHIRICAHUAS

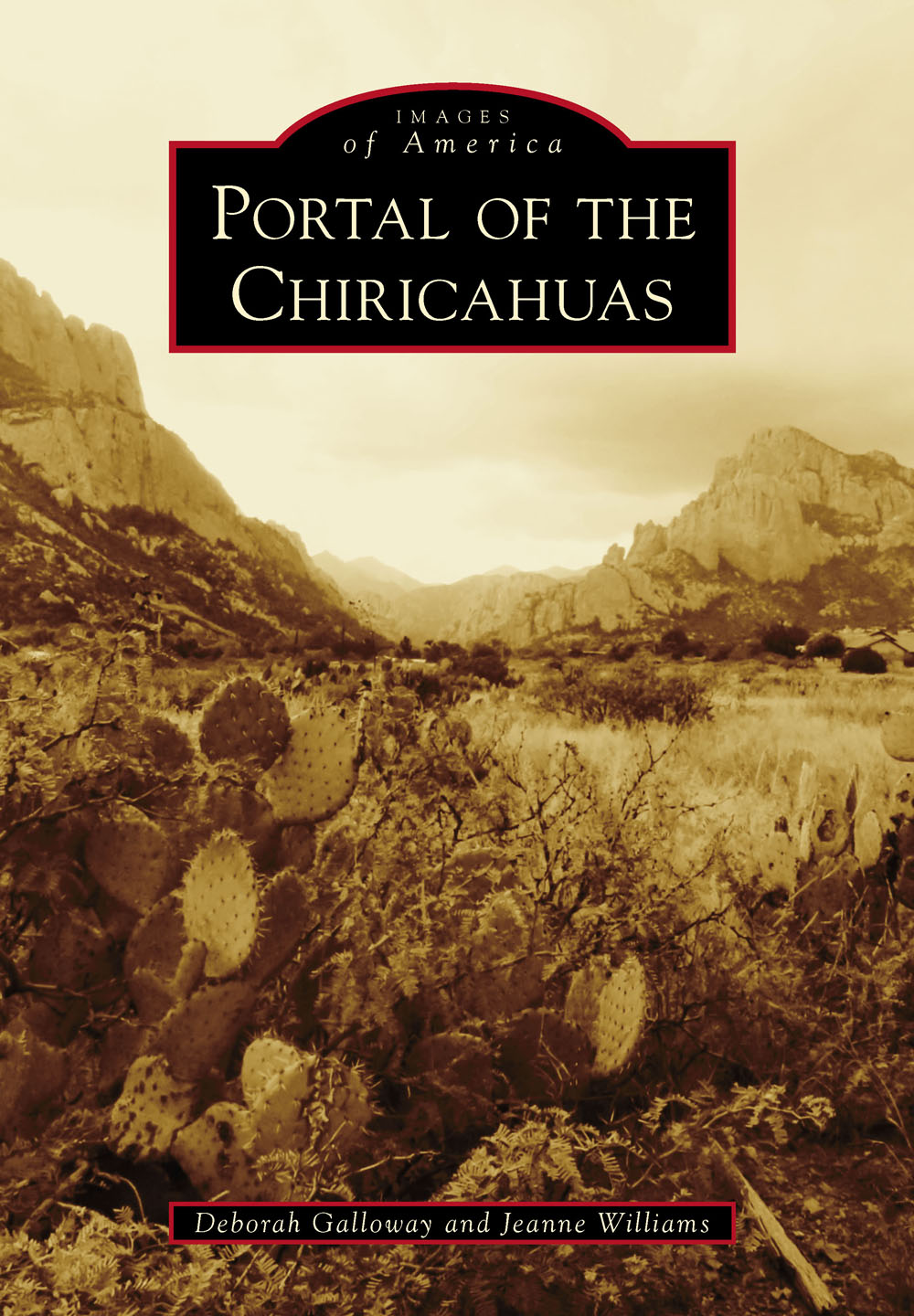

ON THE COVER: Taken by coauthor Deborah Galloway in 2014, this photograph of Cave Creek Canyon shows Cathedral Rock towering at left, facing the Pinnacles with the shaded creek winding between. In winter, white sycamore trunks and evergreens have stark beauty; while the cliffs, veiled in mists, glowing rose and gold, or crowned with thunderheads, are always sublime. (Deborah Galloway.)

IMAGES

of America

PORTAL OF THE

CHIRICAHUAS

Deborah Galloway and Jeanne Williams

Copyright 2016 by Deborah Galloway and Jeanne Williams

ISBN 978-1-4671-1514-8

Ebook ISBN 9781439658154

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016930460

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Sally Spofford, who released birds and spirits to the sky, and to Alden Hayes. He had stories for every trail and loved to share them.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I fell in love with the Chiricahuas on a 1975 backpacking trip with Bill Broyless Tucson group, but I never dreamed I would live here among friends and neighbors who have helped create this book. Deby and I hope they will feel it is their book, a legacy from earlier times.

Roy Bud Hiatt cleaned and annotated photographs saved by his uncle, Jim Frank Cox. Pamela Hulme shared the story and photographs of Willie Mae Sanders, her grandmother. Barbara Miller supplied Maryan and Blackie Stidhams photographs and her own images. Zola Stoltz loaned Maloney/Sanders albums and recounted their heritage. R.W. Morrows letters were augmented by his son, Michael Morrow, who sent photographs and answered questions about his family. Carson Morrows Bull Sheet evokes the mid-1950s. Izzy Escobar located Gomez family photographs that capture Rodeo. Mary Winklers photographs, encouragement, and information have heartened me. Myrtle Bagwell Young reminisced about the Pugsleys and gave photographs. Mel Moe, Mary Willy, Joy and Ray Mendez, and Bill Cavaliere were generous with photographs and knowledge, as was Reed Peters, who also proofread. Thanks for photographs go to Howard Topoff, Helen Snyder, Kim Gee, Shane Burchfield, Barbara Roth, Sally Richards, Frances Grill, Barry Fagan, Sherry Nelson, Phyllis Morreale de la Garza, Tim Lawson, Kim Murphy, Jonathan Patt, Zac Ribbing (Coronado National Forest), Don Wadsworth, Tom Davidson and Karen Tweedy-Holmes. Thanks also go to the National Archives and the Coronado National Forest for images.

Dr. Nancy and Dick Reddy of the Duffner History Project sent us a trove of early Paradise photographs. Bill Gillespie, Coronado National Forest archaeologist, advised and gave information. Debb Johnson helped with problems and took specific photographs. Tamara Winkler, Bonnie Catanzaro, Delane Blondeau, Joan Jensen, Vicki Beno, and Candace Beumler Pardee made pertinent comments, as did Gerry Hernbrode and Orchid Davis, who read text and cheered me on. Laura Zeuner, at all hours, tamed my computer. I especially thank Karen and Eric Hayes for photographs and access to Aldens files.

Henry Clougherty has guided us through this endeavor with unfailing patience, useful advice, and judicious urging. I have worked with many people in publishing; he is the best.

INTRODUCTION

Southeastern Arizona, where the Chiricahua Mountains, under various names, stretch for 150 miles to the Mexican border, was not part of the United States until the Gadsden Purchase was ratified in 1854. The United States paid Mexico $10 million for land below the Gila River, from the Rio Grande to the Colorado River. A railroad route through this region to California was considered the best option, but one senator joked, Now we should pay Mexico ten million to take it back. Still, some forty-niners headed for the Gold Rush noticed forested gashes in distant cliffs as would California Column volunteers marching to repel Confederate forces. Early in 1861, Cochise, a leader of the Chiricahuas, was unjustly arrested, but escaped. Some of his relatives were hanged and he retaliated. The Civil War loomed. Troops were ordered east, and the Butterfield Stage stopped running. Cochise and other Apaches raided encroaching miners and settlers even after soldiers returned. He was weary of battle, however, and in October, 1872, his friend Tom Jeffords helped negotiate a peace that gave Cochises band a reservation covering most of their traditional territory, with Jeffords as agent. Cochise died in 1874; Jeffords retired; and in 1876, the new agent ordered the Chiricahuas to San Carlos, already inhabited by incompatible bands. The Chiricahuas, used to roaming free, repeatedly escaped the reservation for Mexico, killing any whites they met. They still raided through what had been their country. Soldiers were sent to quell the raiders. In 1886, Geronimo made his final surrender. All the Chiricahuas who could be found, including scouts who had tracked them down, were shipped by train to Florida.

Apaches, though they loved their homeland, were comparative newcomers. Over 10,000 years before, big-game hunters wandered into the valleys surrounding the mountains. As the climate grew hotter and dryer, they were followed by people more dependent on wild plants and, eventually, on farming. Mogollon Culture villages thrived in the canyons by AD 1200 but these were abandoned by 1400 because of searing drought. Apaches may have reached the mountains before the gold-seeking Spaniards of 1540 passed by. Traces of a Spanish mine have been found at the mouth of Whitetail Canyon, but there were no settlements in the Chiricahuas though the tireless Jesuit missionary Padre Kino followed the San Pedro River north to where it joined the Gila. He established 24 missions and chapels between 1687 and his death in 1711, including San Xavier, still in use near Tucson. Spains small frontier garrisons could not defend settlers, mines, and ranches, nor could Mexico after winning independence in 1820. The raiding plunder was an important part of Apache economy; they left enough livestock to produce a new crop for their next visit.

Even before the Apaches were marched to San Carlos, prospectors were venturing into the mountains. In 1879, Stephen Reed built his cabin, now the research station directors home, where the North Fork of Cave Creek joins the main creek. Brannick Riggs chose land near the present Chiricahua National Monument, and the mining camp of Galeyville mushroomed in 1881. It was frequented by so-called cowboys who rustled cattle from Arizona to sell in Mexico and vice versa. Supplying beef to reservation Indians and military posts was profitable, and small ranches increased. The Southern Pacific Railroad reached San Simon in 1880, giving men like Reed a market only 35 miles away for his farm products and a shipping point for his cattle. In the mid-1880s, James Parramore and Claiborne Merchant brought in thousands of Texas cattle and organized the San Simon Cattle and Canal Company, which dominated the valley until it was dissolved around 1920.

In early November 1885, a Chiricahua named Ulzana crossed from Mexico into New Mexico and, with only 10 men, terrified the whole region, eluding troops while losing only one warrior. Gus Chenowth was on his way home December 27 with a load of salvage from deserted, short-lived Galeyville when he saw mounted Apaches ahead. He stood up and brandished his rifle. The horsemen angled away. At Turkey Creek, Ulzanas band killed two men, the last of the 38 killed on their 1,200-mile circuit. Four troops of Fort Bowie cavalry lost Ulzanas trail in a blizzard, and the warriors vanished into Mexico. Nine months later, most the Chiricahuas were on a train to Florida. Hundreds evaded capture and lived on in the Sierra Madre. A few, like Masai, escaped from the train and made their way back to the mountains. Burt Lancaster stars in the 1972 film

Next page