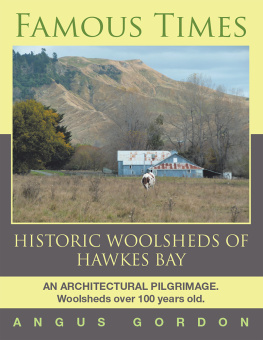

Copyright 2017 by Angus Gordon. 745367

Library of Congress Control Number:2016920118

ISBN: Softcover 978-1-4990-9916-4

Hardcover 978-1-4990-9917-1

EBook 978-1-4990-9915-7

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

Rev. date: 01/19/2017

Xlibris

0800-443-678

www.xlibris.co.nz

I wish to acknowledge and thank the following:

All the woolshed owners who let me photograph their sheds and gave me information on the history of those sheds;

Miriam MacGregor, whose book Early Stations of Hawkes Bay, has been invaluable to me for the early history of a lot of the stations;

Michael and Carola Hudson of Gwavas, and Tom and Joanna Lowry of Okawa, who let me photograph their historic old photos of the shearing gangs;

And I wish to apologise in advance if I have missed out any woolsheds that might have qualified as over 100 years old. I have had to eliminate may fine woolsheds as they didnt fit that category, but I might also have inadvertently just not known about some.

Contents

The idea for this book came to me purely by accident. In 2007 I was approached by a reporter from HB Today who wanted to write an article on myself and my book In the Shadow of the Cape, which I had written in 2004. I said I was reluctant to do another story as I had already had wide publicity over the slip that devastated the hill behind our house in July 2006. The reporter was very persistent, as they can be, and so I said Id only agree if we found a new angle to the story. I was standing outside our own woolshed at the time, talking to Ian Richardson, my partner in a new business doing farm shows for tourists that we had started in the old shed in 2006. I know, I said to the reporter. Im wanting to do a book on the historic sheds of Hawkes Bay, so we can use that as the storyline. This was actually the first time I knew anything about such a scheme, but he agreed, and so I was committed.

I have since travelled thousands of kilometres. I did 1500 kms in my Holden Ute in just three days in the first week of May 2010, driving up every road off Highway 50 to the bottom of the Ruahine Ranges, driving in to Putere and then around the Cricklewood Road, travelling to Weber and then back up the coast, doing what I love best, noseying around a part of the world which goes mostly un-noticed these days, but which, as far as I am concerned, is one of the most beautiful places in the world, with a benevolent climate as an added bonus.

The Hawkes Bay pastoral farming industry was once synonymous with wealth. There was no insult worse that a radical student at Victoria University could throw at you in the 60s than that you were nothing but a wealthy Hawkes Bay Farmers son. I, who had pretensions to being a slight radical myself, by wanting to be a writer and a poet, was loth to admit to my fellow marchers as we processed through the streets of Wellington on yet another protest march, that I had endured a very privileged upbringing in the heart of the enemy territory. Now, and Hawkes Bay is famous for its wine, food, weather, and fruit, leaving the pastoral industry in the dismal position of being rather sidelined, considered a sort of sunset industry, with the lifestyle factor sometimes being the only justification for farmers to cling onto their grossly over-valued properties with minimal cash flow.

I was brought up during the Korean Wool Boom years. In fact I was born in the very year, 1950, when the Korean War began. The next twenty years were ones of great prosperity for farmers. Even farmers on marginal dry land on 500 acres (the standard ballot block size for returned soldiers after the 2 nd World War) could make a good living out of the big three: wool, lamb meat and beef. Most of those 500 acre farms have now either been bought and added onto bigger properties or broken up into lifestyle blocks if they are within the 20 minute range of Hastings, Havelock North or Napier.

That is not to say that all is gloom and doom. A drive down the coast properties, starting from Clifton, and covering the other three intact stations that were part of Clifton; Cape Kidnappers, Haupouri and Taurapa, ducking in at Waimarama and Cabbage Tree Flat, poking into Te Apiti, driving past Waipari (ex Mangakuri shed) Rangitapu, Whenouahou, Te Manuiri, and stopping at Blackhead before travelling on down the coast to the monster Porangahau woolshed, then arriving at one of the jewels of the coast, Tautane, 9000 acres of prime breeding country, passing the lovely Burnview complex before climbing the windswept coastal hills of Akitio and finishing at the graceful shed at Moanaroa, will reveal a wealth of continuing history in the making.

When I was doing the final coast run as I called it, down to Akitio, I took my son Tom, the sixth generation of our family to have lived at Clifton, and an English friend of his, Tony, with me. We stopped at the Herbertville camping ground for the night and ended up having a delicious meal in the Herbertville pub. It was full of rowdy young shepherds from around the area, mainly Tautane, a property that my mothers family, the Herricks, have been involved in for over 100 years. After dinner I went to bed across the way, but Tom and Tony stayed on. They eventually struggled to bed in the wee hours. Tom looked the worst for wear in the morning, with scratches all over his arms and legs and when I asked him what had happened he related to me how he had got involved in an old custom for new shepherds at Tautane. They, and he, had clambered up onto the Steel beam that ran across the room, and had then had to fit themselves through the triangular support bars that reinforced the beam. Needless to say one couldnt be carrying any surplus fat, which is why Tony explained how he was unable to participate.

I set a criteria for this book that the sheds must be over 100 years old, which luckily included the first decade of the 1900s, because it was during this time that many of the huge early estates were being broken up by the Seddon Government and new properties being established, with of course new woolsheds. A classic example of this is the stunning Olrig shed, built in 1907. Others include the Haupouri shed, built by my grandfather at Ocean Beach for his brother Edward in 1906, when that part of Clifton was cut off. After that time the sheds seem to lose their individuality and are mainly built of corrugated iron. Before that and every shed was different from the next, some even being architecturally designed, the main similarities being that they were mainly always made with weatherboard timber on the outside walls, with tongue in groove Matai or Rimu floorboards. Some of the very early sheds, like Gwavas and the Mission shed had wooden shingles on the roofs. These have now been covered over with corrugated iron. The majority of the early big sheds, most of which are still in immaculate order, were built to last, but have all been well looked after as well over the years. The Clifton shed was completely repiled with concrete piles by my father in the 1960s, because of the awkward levels created by the 1931 earthquake.

Some of the very early sheds, like Poporangi, Okawa, Mangatoro are unfortunately beyond repair, but still retain a charm of design, that make them very attractive buildings to look at. One of the oldest, and biggest, the fabulous Maraekakaho shed, so well built that it is still in very good repair, despite not being used to the extent that it was originally intended, is a prime example of all that was elegant, individual and well built in those original old sheds. Part of the reason for the immense size of the early sheds was that they were originally built for blade shearers. For example Clifton was originally a twenty stand blade shearing shed, reduced to a twelve stand shed when machines were introduced in 1904, and then further reduced to a 6 stand shed when one of the six stand shafts was transferred to Haupouri. There could be as many as 40 people involved with shearing in those days, including the shepherds. I have a picture outside the Clifton Woolshed taken in 1893, of about that number. We were fortunate for such a number when the original homestead was burned down in 1898 during shearing time. There was not enough water to save the house but all the antique Indian furniture inside the building was saved though by all the shearers and shepherds and is still in the present day homestead thanks to them.

Next page