Contents

Guide

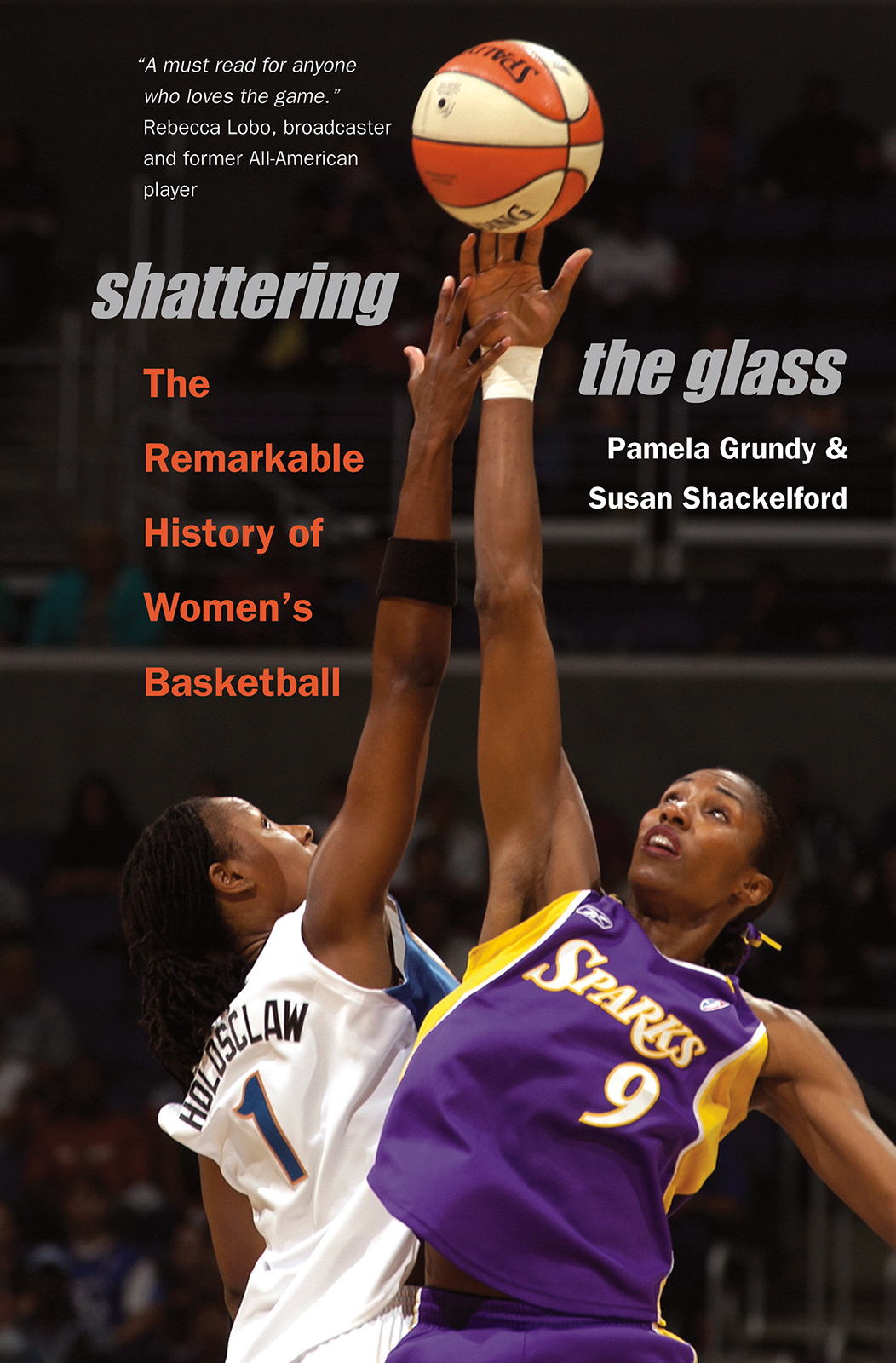

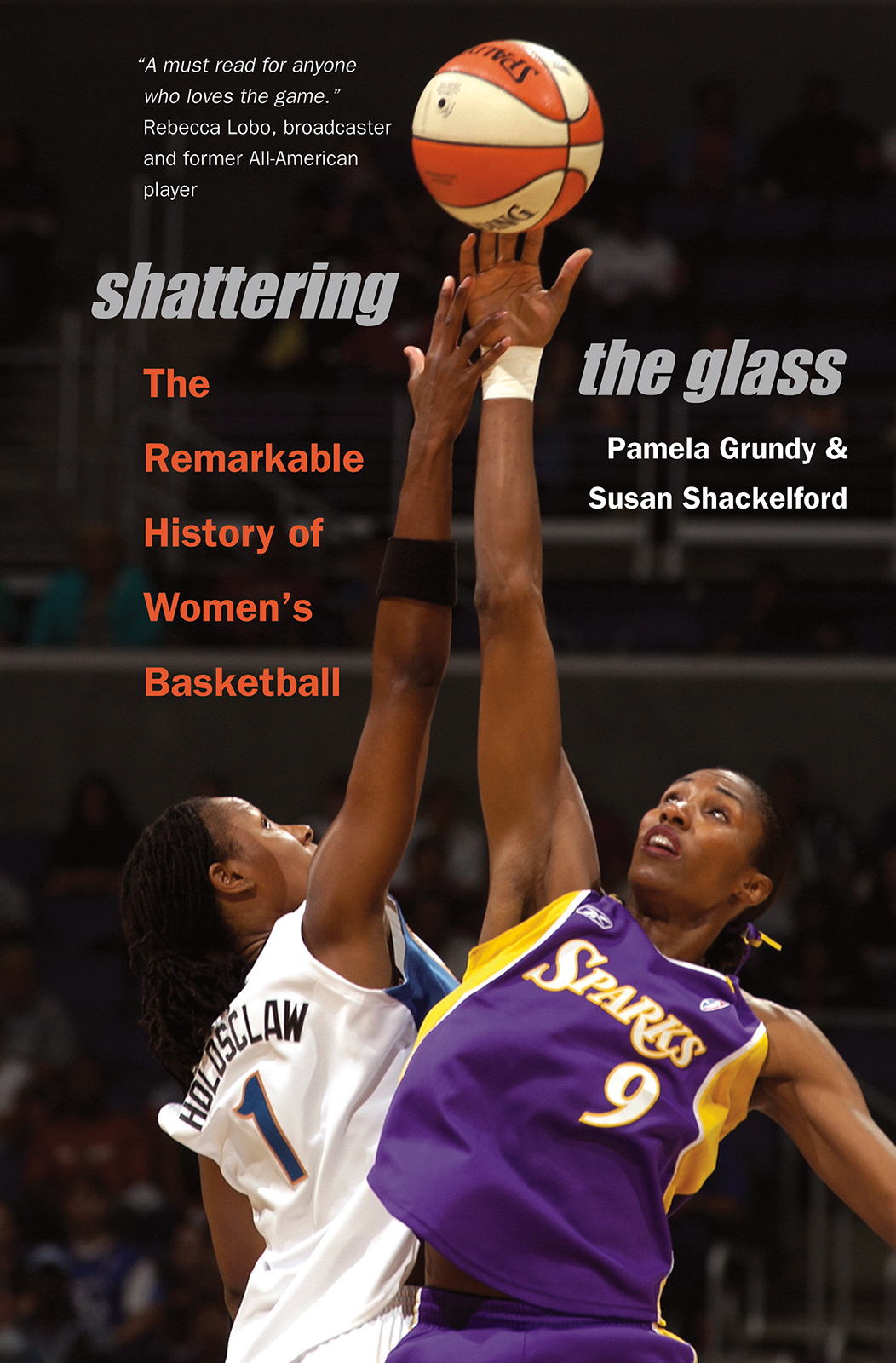

SHATTERING THE GLASS

shattering the glass

The Remarkable History of Womens Basketball

Pamela Grundy & Susan Shackelford

The University of North Carolina Press

Chapel Hill

SHATTERING THE GLASS

2005 by Pamela Grundy and Susan Shackelford

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Originally published by The New Press in 2005.

Paperback edition published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2007 by arrangement with The New Press, New York.

Book design by Kelly Too

Composition by dix!

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Grundy, Pamela.

Shattering the glass : the remarkable history of womens basketball/

Pamela Grundy and Susan Shackelford.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index.

1. Basketball for womenUnited StatesHistory. 2. Women basketball playersUnited StatesHistory. 3. College sportsUnited StatesHistory.

I. Shackelford, Susan. II. Title.

GV886.G78 2005

796.323'082DC22 2005041670

ISBN 978-0-8078-5829-5

11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1

To Pat and George Shackelford,

devoted parents who nurtured both a love of

basketball and a passion for the written word

and to Susan Cahn, who led the way

CONTENTS

NOTE ON CITATION

Any quotations not footnoted in the text come from the oral history interviews listed in the bibliography.

In the text, married women who appear primarily as players are generally referred to by their maiden names, while those who appear primarily as coaches are referred to by their married names. There are three main exceptionsMargie Hunt McDonald, Marianne Crawford Stanley and Theresa Shank Grentzwho appear as coaches and players in roughly equal measure. They are referred to by their maiden names as players and married names as coaches.

Because so many maiden names are used in the text, the oral history interviews have been alphabetized by first name for ease of reference.

Introduction

Sometime in the mid-1940s, Mary Alyce Alexanders father put a basketball hoop in the family backyard. It was a homemade affaira plywood backboard with an improvised rim, more or less ten feet high. Almost instantly, her Charlotte, North Carolina yard became a community center, packed with eager neighbors who played through the day and then, after Mrs. Alexander turned on the porch light, well into the night. Nobody ever waited on the sidelines, Mary Alyce recalled. You just played till you dropped. Sometimes it might be two on three. It might be three on four, or four on four. But everybody always played. Everybody always played. And we played and played and played and played, until we couldnt anymore. And then when they left, I would start shooting.

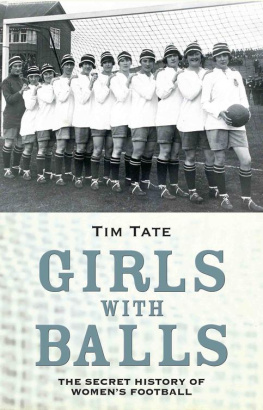

Mary Alyce Alexanders love for basketball echoes across a century of American womens history. Women first took up the game in 1892, almost as soon as it was invented. Throughout the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first, more American women have played basketball than any other sport. Players have been tall and short, fast and slow, gay and straight, from every income level and ethnic background. They have played in cow pastures and on city playgrounds; in immigrant communities and on Native American reservations; in YWCAs and on urban black streets; in schoolyards and gymnasiums without number. They have reveled in the magic of watching the ball drop cleanly through the basket, and in the heady camraderie of no-look passes and perfect plays.

But their story is also one of struggle. For most of basketballs history, competitive athletics has been considered a mans realm. The components of athletic successdiscipline, determination, strength, stamina, assertivenesshave been cast as male, not female, birthrights. As a result, female athletes have found their efforts hemmed in by cautions and restrictions designed to protect them from the strains of heated competition. Many have also faced questions about whether excelling at a masculine activity somehow jeopardized their womanhood, whether through threatening their ability to have children, rendering them unattractive to men or nudging them toward lesbianism.

In 1949, when Mary Alyce Alexander graduated from West Charlotte High School, she ran straight into those assumptions. The boys who had flocked to her backyard and joined her on clandestine forays to the local college gym could take their shot at college varsities. But few schools fielded female teams. Although she excelled in class, her basketball career was over.

Reality hit hard. I guess it would be tantamount to saying youre forced to give up a childhood dream, or youre forced to grow up suddenly, she concluded. Because I thought I would play basketball until I couldnt move anymore. But it didnt work out like that. Didnt work out that way at all.

Such restrictions have meant that even as female players have tested themselves, have dug deep for the courage and the will to rise to athletic challenges, they have also confronted the society around them. Battles for womens sports have gone hand in hand with those for womens rights. Both athletes and activists have worked to highlight womens physical and mental abilities, to win women greater roles in public life and to push views of womanhood beyond fixed definitions of distinctly feminine appearance and behavior. These efforts have taken place at local levels, where advocates of womens sports have battled for the resources required to build teams and institutions. They have also entered the arenas of national politics and mass culture, realms that have wielded growing influence over the shape of local institutions and the way that Americans view themselves.

This history is full of extraordinary individuals. While this work is far from comprehensivethere is just too much to tellthe net we cast is wide. We tell the stories of several generations of basketball pioneers Ora Washington, Hazel Walker, Harley Redin, Nera Whitewhose achievements deserve to be far better known. We also delve into the lives and actions of more familiar figuresSue Gunter, Vivian Stringer, Nancy Lieberman, Leon Barmore, Dawn Staleycharting the roles they have played not only on the court, but in building up the sport they love. Their passion for the game, the joy of sport, rings through the narrative.

But this is no simple tale of steady forward progress. In many ways, our story resembles a game itself, a collection of shifting strategies and challenges, hot shooting streaks and scoreless slumps. A game plan that once was effective falters, forcing players to regroup. Substitutions are required: an emphasis on speed gives way to a need for height and strength, a zone defense to a full-court press. An opponent who tired early on returns refreshed. It is a heated contest, requiring participants to summon all their forces and dig deep within themselves for the resolve to carry on.

Still, there are differences. The players are on their own, forced to size up the opposition on the spot, set their own goals and devise their own plans. The rules change from time to time, requiring entirely new strategies. Most important, their opponents are not individuals but a range of presumptions that limit womens ambitions and opportunities: chief among them the idea that men and women are fundamentally different, in character as well as physically, and that each sex is naturally inclined toward particular activities and destined for specific social roles. Competitors meet these preconceptions in concrete form: the athletic director who views womens sports as a waste of time and money; the mother who fumes because her daughter cares more about her jump shot than her hair; the high school classmates who whisper words like dyke and butch. But the real opposition springs from the ideas that drive such actions, the pervasive assumptions that, often unnoticed, shape our society and our lives.