Introduction

The sun was shining brightly outside, but from the ground right up beside his window there was growing a great beanstalk, which stretched up and up as far as he could see, into the sky.

from Jack and the Beanstalk

Growing up in Latin America, from an early age, I was nourished with all kinds of delicious bean dishes. Refried beans may be the most recognized Latin American bean recipe in North America, but there are hundreds, if not thousands, of culinary formulas that feature beans in Latin America, not to mention throughout the world. Whether they were black, white, red, or speckled, beans made an appearance on my childhoods family table in Guatemala almost daily, sometimes refried but more often transformed into soups or stews, put into salads, or cooked with rice.

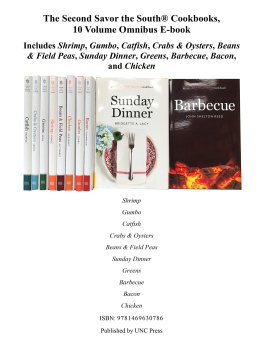

And today, as a cook and cookbook writer in my longtime home state of North Carolina, Ive discovered the Souths equal affinity for beans. I always find ways to incorporate legumes into my familys daily diet, not necessarily because theyre healthy fare (which they are, but well get to that later) but because I just love eating them. I remember places Ive visited by the food I ate, and so many fantastic bean dishes come to mind: the first time I had minestrone, chock-full of red beans, in a restaurant in Rome; my first bite of a salade Nioise featuring tender haricots verts at a beach in the French Riviera; my first bowl of Cuban black beans and rice in Miami; that bowl o red in Houston; and the cup of beans and rice I tasted in Mississippi.

While I didnt grow up on a family porch hulling peas, I have spent many hours in my North Carolina kitchen shelling them by the bushel, cooking them, and relishing their taste. Over the years, Ive fallen in love with the food of the South and learned about its deep history and cultural nuances. Here, for example, I discovered that southerners cook their green beans long and slowlymostly because certain varieties require it and cant be eaten al denteand that with delicious frequency, a few potatoes and some part of a hog will make it into the pot with them.

And then one day I discovered the fascinating realm of field peas. I had already encountered plenty of them in Latin American recipes (such as the gandles, or pigeon peas, in Puerto Rican cuisine) and had eaten my share of black-eyed peas transformed into fritters. I knew well enough that the liquid left over from cooking beans and peascalled likker or pot likker in the South and caldos in Latin Americawas something to be revered. Yet while it was sprinkled with toasted croutons in my family home, I learned the southern way of eating itwith buttermilk and cornbread. But the wide array of southern peas and their many southern-style preparations were novelties to me. That was a lip-smacking revelation indeed.

Beans and field peas are both legumes and seeds/beans that grow in pods. Beans are always dried before and cooked before theyre eaten. Field peas, on the other hand, can be dried or eaten fresh. Green beans are also legumes and pods filled with immature beans, but the pods, of course, are eaten along with the beans. If you slice a green bean in half lengthwise, youll see the immature beans inside; and if youve ever eaten a bowl of cooked half runners, youve probably enjoyed, as have I, finding the tiny, perfectly spherical white beans that escaped their edible green pods as they simmered. As you will see, all of these legumes have different uses in southern food.

Take some beans or peas, a touch of salt, a bit of fat (which in the South is often a piece of fatback, a slab of bacon, or a chunky ham hock), and a good amount of liquid (usually water), and youll end up with a delicious pot of something good. Thats all most legumes require to garner luscious flavor in the South.

Many people around the world eat a diet based on grains and legumes for economic reasons. So when in the 1990s it became popular to refer to recipes that were inexpensive and comfortingmany of which were made of beansas cucina povera or peasant food, I found it interesting that what had forever been part of a way of life for many was now considered trendy.

For generations, beans and peas have graced the tables of southerners, but indigenous peoples of the world have subsisted on diets based on legumes for even longer. Throughout history, beans have provided nutrients and protein to millions of people who couldnt get them from other sources, such as meat, simply because theyre not available to them or they cant afford them. Whether it is Brazil, Africa, or Italy, historically, beans have been the food of the poor. And they still are. That much hasnt changed. Recently, however, beans have broken through class barriers. Now, everyone eats beans. Theyre the culinary equalizer.

Here in the South, it was the same, historically speaking. The poorest people, among them enslaved African Americans, subsisted on mainly peas, beans, grains, and the rare piece of meat, usually the parts of animals that the wealthy considered inedible. However, in the South, beans and field peas quickly crossed over economic divisions. African slaves, who often were in charge of farm and plantation kitchens, greatly influenced the foodways of the South by introducing a harvest of beans and peas into the daily diets of the wealthy families who enslaved them.

George Washington is credited with importing field peas to Virginia when he brought forty bushels of seeds to sow on his own land in 1797. Another aristocrat who planted and ate peas was Americas first epicure, Thomas Jefferson. In his