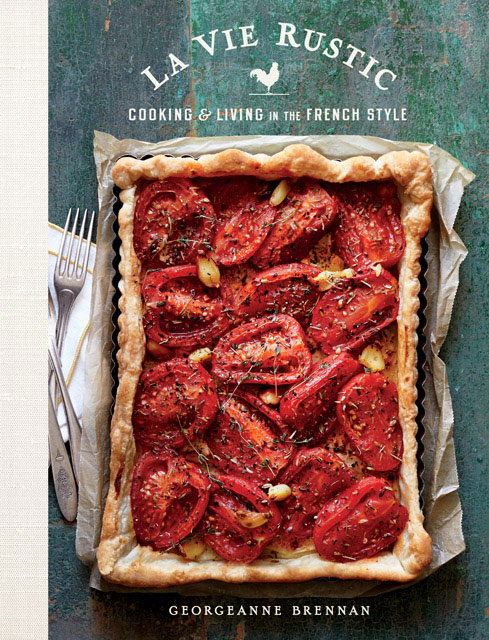

LA VIE RUSTIC

COOKING & LIVING IN THE FRENCH STYLE

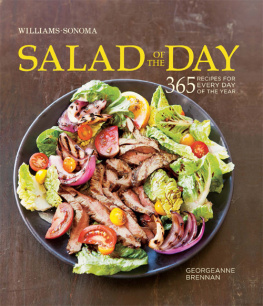

GEORGEANNE BRENNAN

photography by SARA REMINGTON

to Ethel & Oliver

INTRODUCTION

O NCE UPON A TIME, I HAD THE PRIVILEGE OF LIVING AND WORKING IN RURAL PROVENCE, WHERE GROWING AND RAISING ONES OWN FOOD WAS A WAY OF LIFE. TO VARYING DEGREES, EVERYONE had a basse-cour , or barnyard, that supplied eggs, the occasional chicken and rooster for the pot, guinea hens, rabbits, and sometimes ducks or goats as well. Everyone fatted a cochon , or pig, to make the essential charcuterie, from salt-cured hams to pts for provisioning the home pantry.

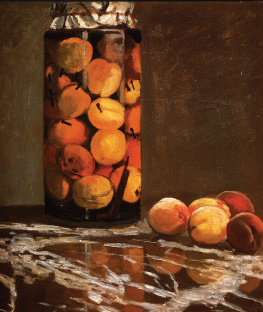

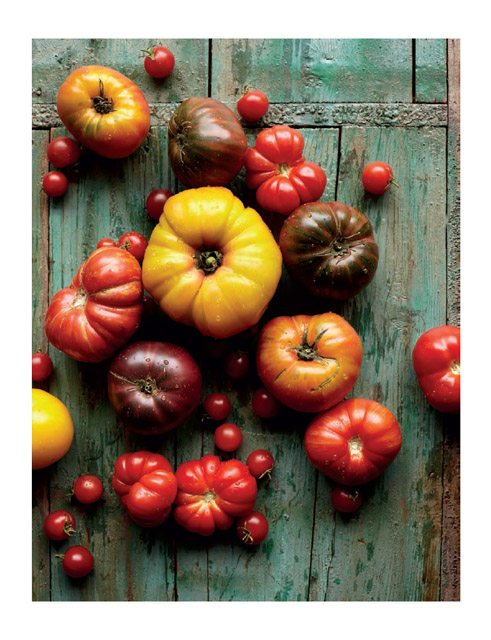

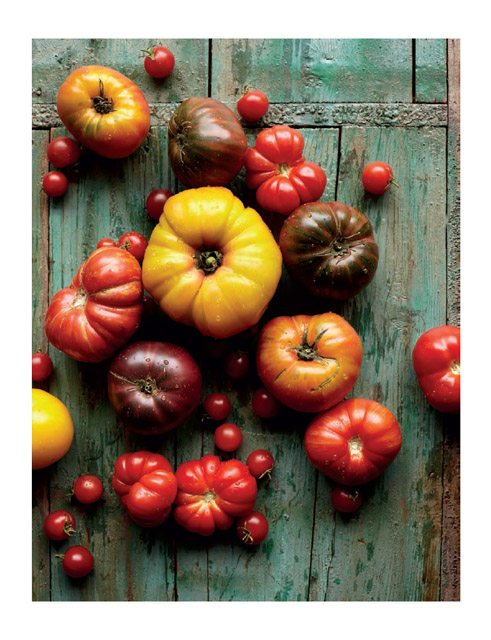

A potager , the essential kitchen garden, planted and harvested throughout the year, supplied a family with vegetables, and a verger , or orchard, was the source of fruits, nuts, and olives. Flowers were planted here and there because beauty should always be a part of life. Fruits and vegetables were harvested for the daily table. Some were preserved as well, with sugar or honey or in wine or vinegar, to use later in the year. For the most part, people took their wine grapes to the local wine-making cooperative, but kept a few bushels to make their own wine, too. Some households still baked bread with homegrown and home-milled grain; others fed their animals with hay, legumes, and grasses produced on their own land. The forest supplemented the bounty of the garden and orchard with mushrooms, truffles, wild asparagus, and dozens of tender wild greens. Thanks to the traditions of local hunting and fishing, wild boar, pheasant, and small birds were also part of the diet, as were trout and other fish from the rivers. Before supermarkets became common, a fishmonger from the coast had a regular route through the backcountry of our region, stopping at outlying farms and hamlets. Sometimes people, especially those with friends on the coast, would make a sortie to the Mediterranean Sea and bring back sea urchins, mussels, sardines, or large fish to roast whole. The seasons dominated both the rhythm of activity and the food on the table.

Over the years, I learned how to cultivate a potager , sniff out the best spots for wild mushrooms, dress a lamb, make my own wine, and propagate fruit trees from cuttings. My neighbors taught me how to cure fresh pork in salt, make French-style pancetta ( roulade or ventrche) , and cook wild birds over an open hearth.

EARLY YEARS IN PROVENCE

On a typical day in Provence, I might have used a traditional hand sickle to cut alfalfa for my neighbor's rabbits, cranked a wheel to draw enough well water to wash my familys laundry, including baby diapers, and helped prune wine grapes. Since we were raising goats for milk and to make cheese and pigs to sell as feeder pigs to be purchased young and fattened by others, a big part of my day was spent milking the goats, feeding the baby pigs, making cheese, and, of course, cooking.

My kitchen in those early years had just a two-burner gas cooktop and an ovenless, wood-burning stove that was primarily used for heat, though I sometimes used the small flat top to simmer a soup or stew. I didnt have an oven, but I became very adept and creative with my limited equipment. And since we picked and foraged much of our food ourselves, there was plenty of prep to be done: I had to wash the dirt off the radishes and lettuces, quadruple-wash the spinach and strawberries, and studiously rid the wild mushrooms of any clinging pine needles or oak leaves and of insidious creatures that may have burrowed inside. Sometimes I felt like I just didnt have the energy to do it all.

The cheese might refuse to curdle, a piglet would escape from its pen, and the sheep-dog would follow the scent of a wild boar (or something), leaving the goats unguarded and scattered. Or perhaps I would just burn the vegetable stew. More than forty years later, I still have a scar on my knee from slipping on the icy ground in winter while trying to catch a goat. In the end, though, the cheese would succeed, the piglet would be captured, the dog would behave, and my next stew would be perfect.

Oddly enough, these days were among the happiest of my life, if also the most difficult. Even on bad days, providing sustenance for my family felt rewarding. The pleasure of rubbing wild thyme into a simmering pot of carrots, onions, sausage, and potatoespeasant foodwas thrilling to me. I learned the rhythm of nature and how it related to my daily life.

After two years and the birth of a second child, our son, we left Provence and moved back to California, where my husband and I became high school teachers. We kept our modest home in Provence and returned every summer, finding again, if for only a few months, that simple life. Without the responsibility of the animals and making a living from them, we were able to enjoy the life of summer visitors, but we were still considered part of the community. Neighbors became friends, and they shared their tables, invited us to weddings and holiday feasts, and told us stories of the two world wars that devastated their communities.

A divorce interrupted the thread of that early French life, but it has nevertheless continued with new friends and family that include a second husband of thirty years, two stepsons, and grandchildren, including a French son-in-law and half-French grandsons.

PROVENCE TODAY

When it comes to that part of Provence today, the traveling fishmonger is long gone, but the open markets continue. Village supermarkets have become more common, offering an astounding array of food, from fresh rabbit to organic cheeses. My neighbors still have big gardens and orchards, and I continue to learn something new about a sustainable life whenever I visit. I admit, however, that I am grateful for the hot and cold running water and my washing machine. I dont have room for a dishwasher or a clothes dryer, but if I did, I would install them. I now have a four-burner gas stove and an electric oven outfitted with a rotisserie. Even though the oven is twenty-five years old, it serves me well.

Along the way Ive learned such wide- ranging things as the traditional thirteen desserts of a Provenal , and how some olive mills still use heavy stone wheels to crush the fruit to oil.

Little did I know it at the time, but my first years in France gave me the foundation for my lifes work as an entrepreneur and food writer and changed me forever. The more I learned, the more I began to realize not only how delicious these foods were, but how this relationship between land and table is more than just sustenanceit is the warp and woof of French life, no matter how humble or grand. The tapestry has become more fragile and frayed in urban areas, true, but in the small villages and rural regions that form the landscape of so much of France, the matrix of barnyard, orchard, garden, and the wilds of land and water is not an artifact of a bygone era or a show put on for tourists. It remains the basis of daily life, if not in practice, at least in spirit.

People from the cities still head out to the country on the weekends, to visit family and friends, to have a long lunch, and to bring home whatever is locally grown or produced. The sea draws them with early-morning fish markets and sea urchin collecting. In fall, cars line the roadsides helter-skelter, temporarily abandoned by their owners whove gone in search of mushrooms.