The Angels Share is an imprint of

Neil Wilson Publishing Ltd

www.nwp.co.uk

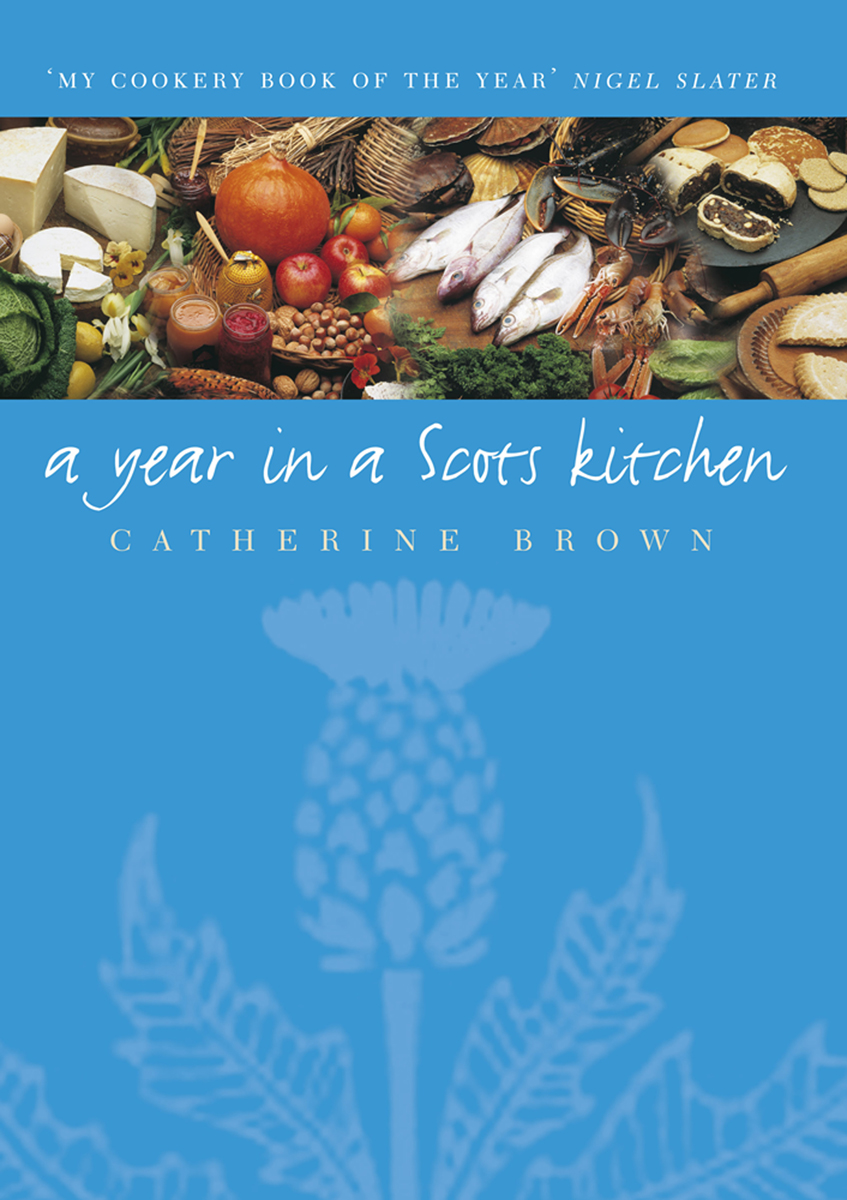

Catherine Brown 2011

First published in 1996. Reprinted in 1998, 2000, 2002, 2009.

The author asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Print edition ISBN: 978-1-897784-79-2

Ebook edition ISBN: 978-1-906476-84-7

Contents

DECEMBER

Oatcakes baked in the oven

AUGUST

Pickled lamb-mutton broth

With thanks

The editor had an idea for a new column, could we meet for lunch? The Penguin Caf perched above Glasgows Princes Square, as I remember, was the venue and I arrived feeling pleasantly expectant at the prospect of a new challenge. So what was the subject? Scottish food. Knowing how much I had already written on the subject, he thought there was an angle in exploring the past and the present, side by side.An old-established traditional method beside a modern, updated style. I could do a potted history of the tradition, some investigative interviews with the artisans and craftspeople in the food world, and we would call the column Great Scottish Food.

Without this push, in the early 1990s, back into a subject which I had decided held no more mileage for me, the seed for this book would not have been planted. To the late, great, Arnold Kemp, editor of The Herald from 198094, my sincere thanks. To The Heralds chief assistant editor, Anne Simpson, who fed, watered and nursed it with immense skill and enthusiasm during the first year of its life, also my sincere thanks.

Besides the weekly-column idea, there was also the suggestion that if I managed 1,000 words a week on Scottish food for 52 weeks, at the end of the year there would be enough material for a book. And so there was. But by this time the seed had grown into a tree with too many shooting branches. To produce fruit it had to be pruned and shaped into the right form. From 1992-95 a number of different pruned and reshaped versions hit a considerable number of publishing editors desks in the UK, every one accompanied by Fiona Taylors illustrations from the Great Scottish Food series, and every one rejected. Then, just as it seemed as though its death was imminent, one helpful London publisher (Anne Dolamore at Grub Street) suggested I send it to Neil Wilson Publishing (previously of Lochar). He might be interested. To Neil Wilson my sincere thanks for having the courage to take on this book.

While Arnold, Anne and Neil are the key people who made this book possible, a great many others have fed, watered, pruned and shaped it throughout its growing life.

Iseabail Macleod, Editorial Director of the Scottish National Dictionary Association, has edited it with great skill, enthusiasm and encouragement. Robert Stewart has acted as my agent in Scotland providing more enthusiasm, encouragement and advice. Neil Wilson Publishing has skillfully and sensitively cared for the practical making of the book. A great many artisans and craftspeople throughout the food industry the guardians of our culinary treasures have given it much of its colour and character. Many academics with specialist knowledge, as well as food industry experts have freely provided me with valuable information. Esther and Ailie (my daughters) have been my toughest critics.

To you all, my sincere thanks. The harvest is yours. Enjoy it.

Measures

M-day (30 October, 1995) was the first phase of metrication, when pre-packaged food and drink (except for pints of beer and cider in pubs, and pints of milk in glass bottles) changed.

Loose, over-the-counter sales, have a reprieve, but only until 1 January, 2000, when selling lbs and pints in any form becomes illegal.

The march of metrication, of course, is about standardization in Europe. Whether youve joined the Imperial Measurements Preservation Society, or not, metric units are not aliens from outer space. Theyre simple, easy measures, and they are already all around us in existing food and drink. Children in school have been taught metric measures since 1974.The easiest way to learn is from the packaging youre already buying. If you get wise to the proportional differences, you become a free-thinker with a dual choice.

For a rough guide to buying foods sold loose in metric the proportional differences are:

| Imperial | Metric |

| lb | 100g (slightly less) |

| lb | 250g (slightly more) |

| 1lb | 500g (slightly more) |

| 2lb | 1 kilo (a little more) |

| 1 pint | 500ml (slightly less) |

Dual thinking on a proportional basis in recipes works more or less the same way :

| Imperial | Metric |

| 1oz | 25g (slightly less) |

| 4oz | 125g (slightly more) |

| 8oz | 250g (slightly more) |

| 1lb | 500g (slightly more) |

| 4fl | oz 125ml (slightly more) |

| 5fl oz ( pint) | 150ml (almost the same) |

| 8fl oz | 250ml (slightly more) |

| 1 US cup |

| 10fl oz ( pint) | 300ml (almost the same) |

| 20fl oz (1 pint) | 500ml (slightly less) |

| 40fl oz (2 pints) | 1 litre (a little less) |

Despite several attempts to standardize with Europe, the US has resisted metrication and continues to measure both liquids and solids in their convenient cups based on proportions of 8fl oz ( US pint) which is almost 250ml.

Sets of US cup measures are very convenient measures, and wherever possible, I have used them in the recipes. An 8fl oz cup can be used instead of the measure though they are now usually available in cookshops and some supermarkets.

A tablespoon is 15ml; a dessertspoon, 10ml and a teaspoon 5ml.

Only in baking recipes is it necessary sometimes to make more exact conversions.

The Scots Gardner:

published for the climate of Scotland

by John Reid, Gardner, 1655-1723

To Reid, whose Gardners Calendar and list of Garden Dishes, and Drinks in Season is reproduced at the end of each month, we owe a particular thanks for his work as a pioneering gardener. Many pleasure gardens attached to historic houses were influenced by his skill in garden layout a new phenomenon in the late 17th century as the need for fortified homes diminished. But besides this talent, Reids interest extended beyond the formal lawns and be-flowered borders to the kitchen garden where his vigorous enthusiasm for growing fruits, vegetables and herbs, as well as tending his hives of bees, is especially valued.

Reid left Scotland in 1683 at the age of 28 (the same year that The Scots Gardner was published) to begin a new life in New Jersey, encouraged by reports of the good climate and fertile land, but also to join a community of fellow Quakers seeking freedom from religious intolerance in Scotland. He was the first Scot to write a gardening book with Scottish conditions in mind. He was the second professional gardener to write a Gardners Calendar, the English John Evelyn, being the first. Reids gardening message may be 300 years old, but Scots must still find practical solutions to the cold, chilled, barren, rugged-naturd ground, as he describes it. The temptation may be to say it cant be done. Asparagus and artichokes in Scotland? If Reid could do it, then why not in modern times.