Smithsonian Books

Washington

1999 by the Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

TUPPERWARE is a registered trademark of Dart Industries Inc.

Copy editor: Joanne Reams

Production editor: Deborah L. Sanders

Designer: Chris Hotvedt

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clarke, Alison J.

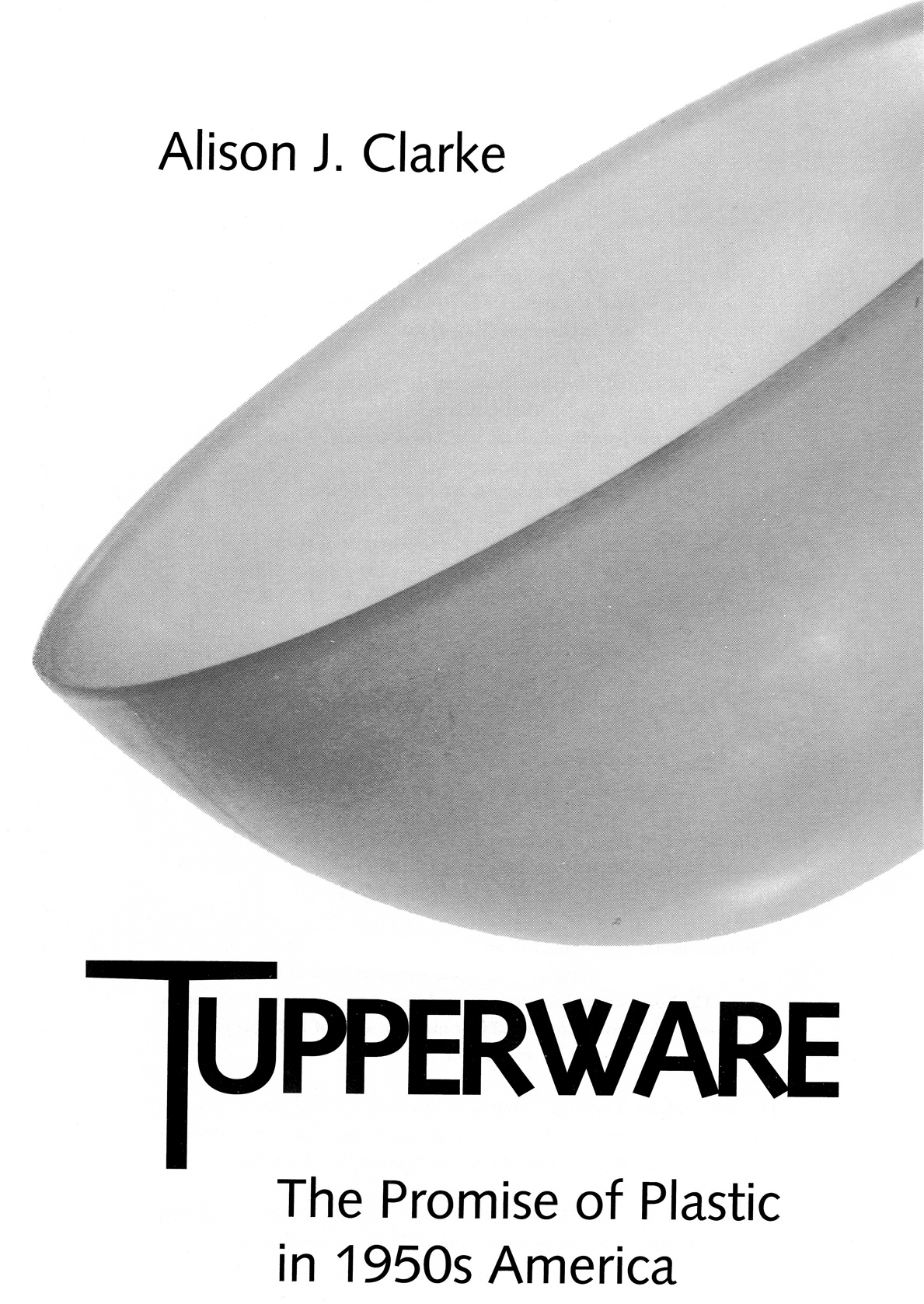

Tupperware : the promise of plastic in 1950s America / Alison J. Clarke.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-56098-827-4

1. Tupperware (Firm)History. 2. Plastic container industryUnited StatesHistory. 3. Tableware industryUnited StatesHistory. 4. Plastic tablewareUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

HD9662.C664T863 1999

338.76684970973dc21 99-16972

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data available

eISBN: 978-1-58834-436-6

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-56098-920-2

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the individual captions. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually, or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

The objects pictured on pages ii and iii of this book are details of the photograph on . Tupper, Earl S. Kitchen containers and implements. 194556. Photograph 1999 The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Tupperware: The Promise of Plastic in 1950s America is not sponsored or endorsed in any manner by Tupperware Worldwide / Dart Industries Inc.

This book may be purchased for education, business, or sales promotional use. For information please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books, P.O Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013

www.SmithsonianBooks.com

v3.1

For Constance Loadwick White, with love.

...

Contents

one

To Be a Better Social Friend

two

Tupperware

three

Poly-T: Material of the Future

four

The Hostess with the Mostest

five

Parties Are the Answer

six

Faith Made Them Champions

seven

A Wealth of Wishes and a Galaxy of Gifts

eight

TupperwareEverywhere!

...

Acknowledgments

Without the insight of Tupperware dealers, hostesses, and managers from the 1950s to the present day in the United States and United Kingdom, this book could not have been written. I thank the many people who contributed time in relaying their oral histories concerning the product and corporation. Several of the past executives from the company were enthusiastically supportive of the research and genuinely interested in the products cultural history. I am particularly grateful to Elsie Mortland, Joan Jackson, Joe Hara, and the Flaherty family.

Fellowships at the Smithsonian Institutions National Museum of American History proved invaluable in supporting archival research. There I benefited from the expertise and encouragement of numerous staff members and Smithsonian fellows, including Katherine Ott, Steve Lubar, Anne Serio, Barbara Clark Smith, Bill Yeingst, Rodris Roth, Tom Bickley, Mimi Minnick, John Fleckner, Charlie McGovern, Fath Ruffins, Reuben Jackson, Vanessa Simmons, Meg Jacobs, Shelley Nickles, John Hartigan, Scott Sandage, Pete Daniel, and Mary Dyer. I acknowledge the efficient and inspired help of my summer research intern, Jenny Chun. I also thank the library staff at the National Museum of American History, especially Stephanie and Jim, and all the staff of the Archives Center and the Division of Domestic Life.

Big thanks to Dick Hebdige, Jeffrey Meikle, James Horn, Ann Smart Martin, Dell Upton, Penny Sparke, Roger Horowitz, Gary Kulik, and colleagues at the Royal College of Art for thoughtful advice at the early stages of my research. I am particularly grateful to Professor Christopher Frayling for his initial encouragement of my Tupper Magic pursuit.

Research supported by a grant-in-aid at the Center for the History of Business, Technology, and Society at the Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware, in the summer of 1996 provided vital supplementary details regarding plastic manufacture. Similarly, for background information concerning contemporary sales companies Elizabeth M. Doherty at the Direct Selling Association, Washington, D.C., generously offered the organizations library and resources for my use.

Numerous kind colleagues and friends have offered constructive criticism of this research over the lengthy period of its completion and endured endless Tupperized ranting. I thank Matthew Hilton, Maria Blyzinsky, Clayton Harris, Michael Carroll, Jeremy Eaton, Deborah Ryan, Judy Davies, and Carolyn Corben. Without the generous hospitality and banter of Noah Steinberg and Josh Cohen my stay in D.C. would have been far less enjoyable; thanks, you two. Many thanks also to Rachel Fincken and Mr. Williamson for sharing, in different ways, the more sociable and spiritual dimensions of research and life in Washington, Brighton, and New Orleans.

Special thanks to Daniel Miller for his patience, wit, and inspiration and to my kind and insightful acquisitions editor, Mark Hirsch, for showing sustained support and enthusiasm for this project. I am most grateful for the conscientious work of Joanne Reams, Deborah L. Sanders, and the Smithsonian Institution Presss anonymous reader.

Paul Foster and the Clarke family have shared the project, in some form or another, from its initiation through to its completion, and I owe them all much more than thanks for their love and unerring support. I dedicate this book to them and to my grandmother, the redoubtable, fun-loving Constance White.

...

Introduction

A Tupperware party takes place somewhere in the world every 2.5 seconds, and an estimated 90 percent of American homes own at least one piece of Tupperware. Since the mid-1990s, around 85 percent of Tupperware sales have been generated outside the United States in countries as diverse as South Africa and Japan. Artifacts ranging from Wonder Bowls to Ice-Tup molds, fitted with the patented Tupper airtight seal, have equipped the kitchens of millions of households since their inception in 1940s America. An icon of benign suburban living, described by one commentator as being as all-American as the stars and stripes, Tupperware remains inextricably bound to the sociality of the party plan direct sales system that has been appropriated across the world.

Although competitors such as Rubbermaid use conventional retailing and advertising methods (distributing most of their plastic containers through supermarkets and hardware stores), Tupperware relies ostensibly on word-of-mouth recommendation and practical demonstration techniques of a specialized dealer. In a modern consumer culture premised on increasing standardization, self-service, and efficiency, the Tupperware party (which gathers a predominantly female group for a product demonstration in a convivial atmosphere) defies the logic of contemporary marketing strategies. The majority of

When an amateur inventor and designer named Earl Silas Tupper first invented Tupperware around 1942 (from a refined version of polyethylene that he referred to as Poly-T: Material of the Future), he envisaged the total Tupperization of the American home. House Beautiful hailed Tupperware designs as Fine Art for 39 Cents with gorgeous textures reminiscent of jade and mother-of-pearl, but American housewives remained largely unimpressed. Department store displays and newspaper advertisements promoted Tupperware as the answer to the dreams of the modern homemaker, but still sales dwindled.