This book would not have been possible without the advice, assistance and recipes provided so generously by Sara Joseph. I thank her deeply for her kindness of spirit.

Devi Bharathan, Ayisha Mohammed, Lissie George, Chandralekha Shenoy, Shalini Jayaprakash and Resmi Sunil contributed recipes specific to the different communities that make up the mosaic called Kerala; K. Sreedharan and K. Bharathan answered questions and cleared doubts; Aruna Ghose gave books and advice; Ammu Kannampilly and Ravi Ahmad provided research assistance; Ajay Kumar did the initial keying in; Vijander Singh Rawat transformed a muddled up typescript into a readable one; and Sherna Wadia edited it into shape.

I thank all of them.

Introduction

CASTES, CUISINES AND CONFLUENCE

A Brief Note on Malayali Culinary History

What we choose to eat or refuse to eat, and how we eat it defines us as much as our culture and language. If we are what we eat, then the Other is what he is because of what he eats or refuses to eat. Cuisine creates a community; it also keeps communities apart. Food defines, both positively and negatively. Unfortunately, barring a few exceptions and despite the path-breaking work of the late Achaya, the dialectics of food, as culture, as cause and effect of socio-economic changes, as history, has not exercised the minds of most scholars. The indifference is a pan-Indian phenomenon. The history of Malayali food remains unwritten, despite the coming of age of a whole new generation of talented historians. What follows is at best, a sketchy outline, some speculation and one conclusion.

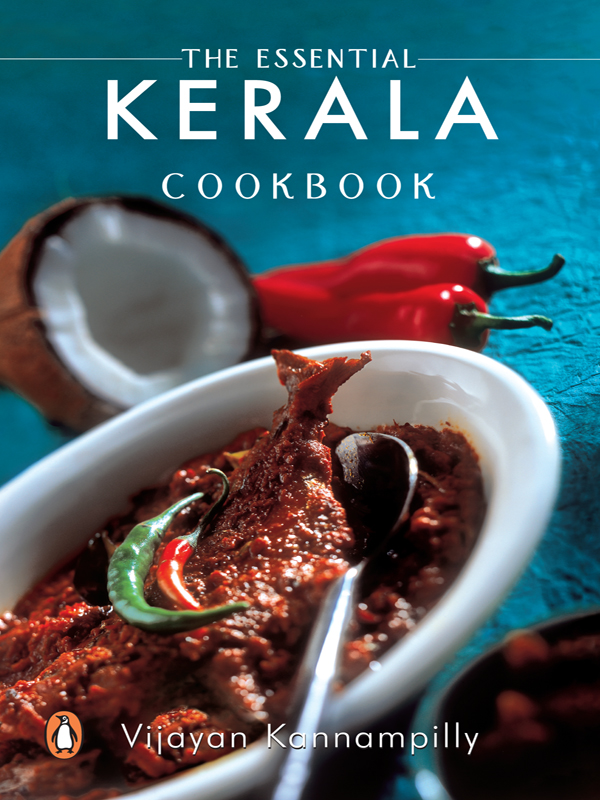

Malayali cuisine as we experience it today is a coming together of three different traditionsHindu, Christian and Muslim. Though all of them are made up of sub-denominational and regional practices and tastes, the Hindu tradition also has caste differentiations and overtones. Thus while the vegetarian cuisine of the Namputhiris and Nairs do not differ on the whole, the Namputhiris and the Ambalavasis (those who perform ritualistic roles in temples) also abjure garlic, onion and shallot. Within the Hindu culinary tradition there also exist the cuisines of two other vegetarian communities of emigrantsthe Tamil Brahmins and the Konkani Gauda Saraswats. While the former group has more or less adopted the Namputhiri-Nair cuisine, the latter has retained its cuisine with subtle incorporations of local produces and some stylistic variations.

Despite the vegetarianism of the Namputhiri-Nair cuisine and the caste hegemony exercised by them, the majority of Malayalis, at present and in the past, are non-vegetarians with a catholicity of taste that now includes beef. At this point it is important to stress that non-vegetarianism in Kerala does not imply (as in the West) that the main course or the heart of the meal is a meat or fish preparation. The typical middle-class Malayali meal today consists of parboiled rice eaten with a gravy of vegetables and pulses, with a complement of dry vegetable preparations, pappadum, pickles and a fish or meat dish. This is true for all non-vegetarians. In fact, a meal at any roadside restaurant or teashop would be just this.

The word kari in Malayalam though written as curry in English does not always mean a dish with gravy. It means a pungent, spicy meat or vegetable preparation. (One exception to the general rule is madhura kari, a Muslim sweet dish.) In Malayalam it also means a pickle. The other meaning is anger. Kari also has a literary side. When the Namputhiris used to perform the dance Sangha Kali at a feast, a set of verses called the kari slokam extolling the specialties served at the feast was a part of the performance! The word kari in fact comes from the Tamil word for black pepper, the favoured flavouring while preparing meat and fish dishes. The English transformed the word to mean a spicy dish with gravy.

In Malayali cuisine the kari has two forms ozhichhukootan kari and thottukootan kari. The first means curries like, pulinkari, pulisseri and sambar that have gravies and the second are dry. As a rule the meat or fish dish with daily meals is a thottukootan kari. In a specific cultural sense this means that most Malayalis do not have any inhibitions about eating fish or meat.

It is in the cooking of meat, poultry and fish that the Malayali makes full use of the produce of the Spice Coast. For this they have to thank the culinary genius of the Christian and Muslim communities of the state. Unlike the rest of India, Keralas caste system was notable for the absence of an identifiable Vaishya or trading caste. This, plus the mercantile skills and entrepreneurial talents of the Christians and Muslims, made them natural entrants into the spice and other trades and the forerunners of an indigenous mercantile community. In fact, at least two spices which are now associated with Malayali cuisine clove and nutmegcame through trade originally from the Spice Islands, Malacca, now called Maluku, and later more extensively through the Dutch.

Unlike North Indian vegetarian cuisine, in the preparation of vegetables the Malayalis reach, as a rule, does not extend beyond pepper, cumin and chillies. Traditionally, the use of spices, barring pepper and some of the green spices, were confined mostly to the preparation of Ayurvedic medicines.

The humble chilli too, has a foreign connection. Achaya points out the word for chilli in most Indian languages is an extension of the word for pepper. The Malayalam mulaku for chilli is derived from the Tamil word milagu for pepper, while pepper itself in the land of pepper becomes kuru-mulaku, meaning seed chilli! Before the introduction of chillies, pepper was extensively used to flavour dishes and it was the key commodity of the spice trade.