Ebury Press is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This digital edition published in 2017.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

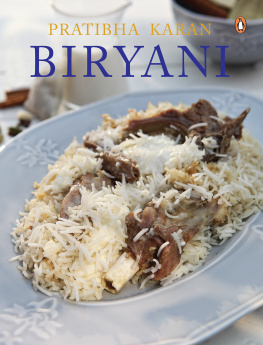

Introduction

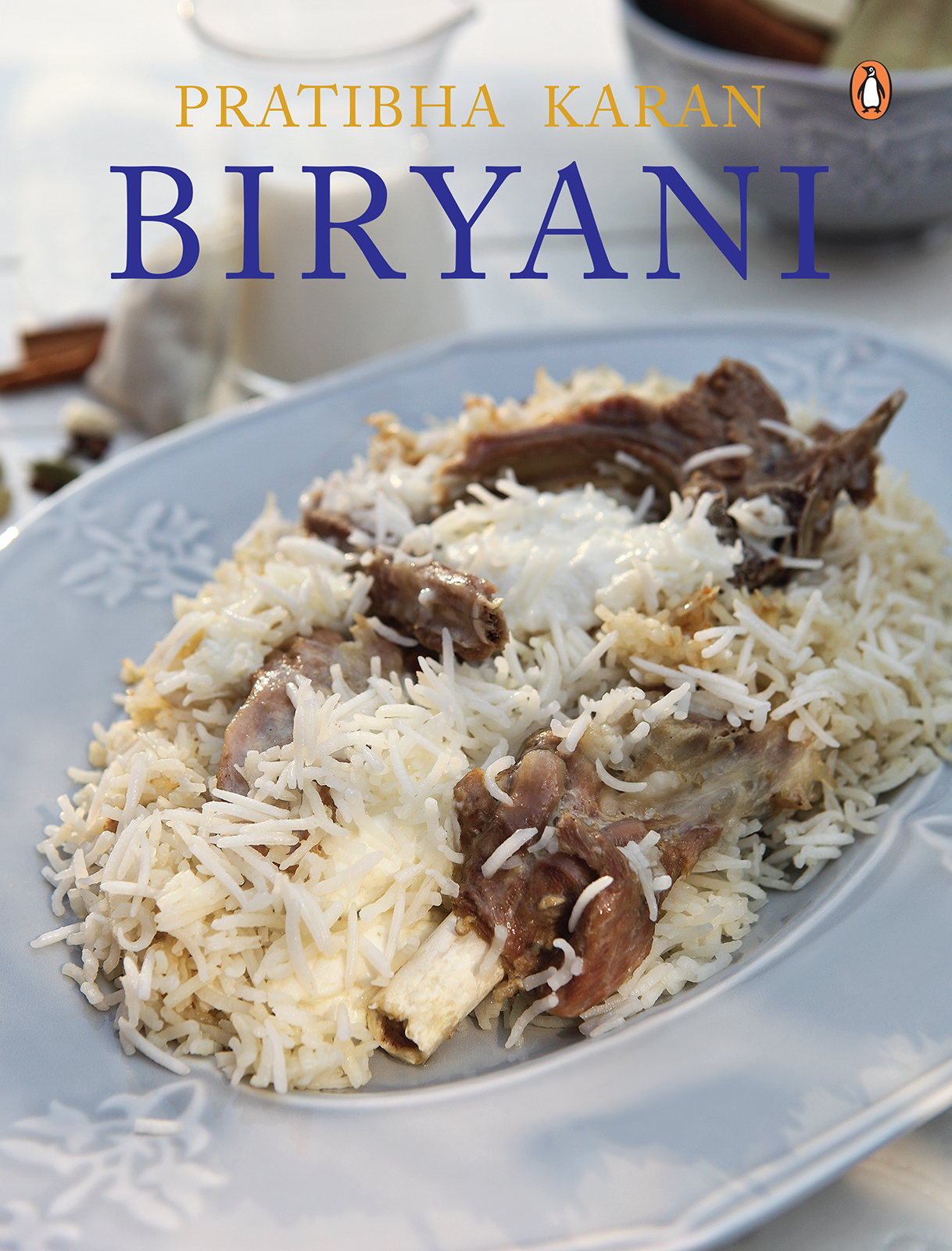

If there is such a thing as food of the gods, it is undoubtedly the biryani. No dish can match it in grandeur, taste, subtlety and refinement. The magic of biryani lies in the way rice is transformed into something ambrosialabsorbing the rich flavours of meat and spice, scented with the dizzying aromas of saffron, rose, jasmine or screwpine; the white grains taking on a gem-like mien.

The Indian subcontinent owes a deep debt to the Muslim community, for it is they who introduced the gamut of biryanis and pulaos to us. The dish has since spread through the country and taken many forms. Depending on the place, its culinary history, and the availability of spices, biryanis and pulaos can be markedly different. Some biryanis, for example, lay emphasis upon one particular ingredient or spice, which then lends its own flavour to the dish. In Bengal one finds the use of mustard seeds; the biryanis of southern Maharashtra are famed for their use of chillies.Traditionally too, biryanis would be cooked using the local variety of rice, such as the kaima of Kerala or the kala bhaat of Hyderabad which, when cooked, would permeate an entire home with its seductive aroma. Today, however, most biryanis are made with the famed long grained basmati rice.

In this book, I present before you a dazzling range of such biryanis, from across the length and breadth of the country. When I began researching for this book, one of the first surprises to greet me was the discovery that there are more biryanis in south India than the north, despite being associated with the Mughal and Awadhi culinary culture. And south does not mean just Hyderabad. Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala have a surfeit of biryanis, with many towns in these states possessing their own signature versions of biryanis. Similarly, western India, especially Mumbai, home to Muslim communities such as the Khojas and Boris, also boasts of a large variety of biryanis. Only the east, with the exception of Kolkata, seems somewhat bereft. With some effort, I was able to locate just one biryani in Assam called the Kampuri Biryani, named after Kampur, the town to which it belongs. In the interest of equitable representation, several biryanis of Delhi, Lucknow, Hyderabad, Kerala etc. had to be left out.

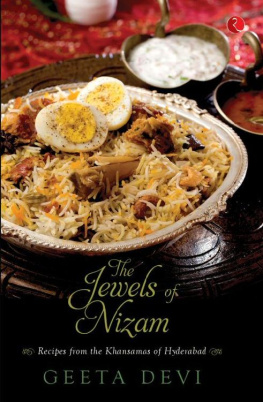

Among all the biryanis, the thoroughbreds are from Hyderabad. It is said that about forty kinds of biryanis alone are made in Hyderabad, which is not surprising on account of its location and history. The cuisine seems to have borrowed something from everywhere, and not just from all over India, but also from Persia and Arabia. Journalist Vir Sanghvi, perhaps Indias most famous food writer, was told very categorically in Lucknow that the real biryani was made only in Hyderabad and that Lucknow had only pulaos. He writes that the famous Dumpukht Biryani served in the Dumpukht restaurants in the ITC hotels drew its inspiration not so much from Awadh, but from Hyderabad.

The origin of the word pulao is well known, but the origin of the word biryani seems somewhat hazy. Pulao comes from the Turkish word pilav or pilaf, the Persian word polou and the Spanish word paella. All of them seem to have a common origin. They say that the word biryani comes from the Persian word birinj, meaning rice, which seems quite plausible. But the Dumpukht restaurants in the ITC chain of hotels claim that birinj means frying before cooking. This hardly leads us to the biryani. The hotel chain also claims Taimur the Lame brought biryani to India in the fourteenth century. One is not sure whether the claim is as apocryphal as its claim on the origins of the melting Kakori Kababthat it was invented for an Awadh king who could not chew as he had lost all his teeth.

In all probability, the pulao (if not the biryani) originated as a war meal. After a days battle, the cooks could not be expected to organize a meal in courses for the soldiers, except maybe for the generals and the kings. So they would cook rice with meat or poultry and maybe vegetables thrown in, in one huge deg or pot, thus giving the world this delicious dish.

What is pulao, and what is biryani? Talk of their differences is unending, but in actual fact, there is a very fine dividing line between the two. Both are rice dishes cooked with meat, poultry, seafood or even vegetables and both can be absolutely irresistible. Though the procedure of cooking them is quite different, there prevails an amusing mix-up among them, with some pulaos being named as biryanis and vice versa. For instance, the Hyderabadi Doodh ki Biryani is actually made the pulao way. Again, the Hyderabadi Keeme ki Khichdi is not a khichdi but a biryani. And there is one biryani, also outstanding in taste, that is not made with rice but with vermicelli.

Broadly speaking, the following are the distinguishing features of the two. The cardinal principle of a biryani is that it is made by the method of layering in a pan, with rice being the first layer and the last layer, and meat, fish, poultry or vegetables constituting the middle layer. Sometimes, there are just two layers, with rice constituting the first and meat, poultry or fish constituting the upper layer and vice versa. Sometimes rice and meat or poultry or vegetables are also arranged in four alternating layers. In the pulaos, however, there is no layering and the rice and all the other ingredients are cooked together, in a kind of potpourri.

Generally, biryanis are scented with saffron, rose, screwpine or jasmine, whereas pulaos are hardly embellished with any essence. Biryanis also use more spices than pulaos, and are wetter than pulaos. In pulaos, on the other hand, whole spices (khada masala) are used more often. Biryanis are generally made with par-boiled rice whereas pulaos are cooked in just sufficient water and, when done, the rice fully absorbs the water. A lot of pulaos are also made in chicken or mutton stock. Over the years, the pulao has also been vegetarianized in northern India obviously by and for the predominantly vegetarian population in this region. In Delhi and Lucknow, it is widely believed, that pulaos are superior to biryanis. Today, rice dishes flavoured with cumin, onions or only green peas are also called pulaos.

One thing that is common to biryanis and pulaos is that towards the end both are cooked on slow fire. This procedure is called dum. The cover of the pot is either sealed with dough or a heavy stone is placed on top of it. Alternately, hot coals are placed both under the pot and on the lid. In fact, from dum has come the word dumpukht (or dumpokht in Hyderabad), which means sealing the dish tightly, in the process trapping the aroma and flavours inside the pot.