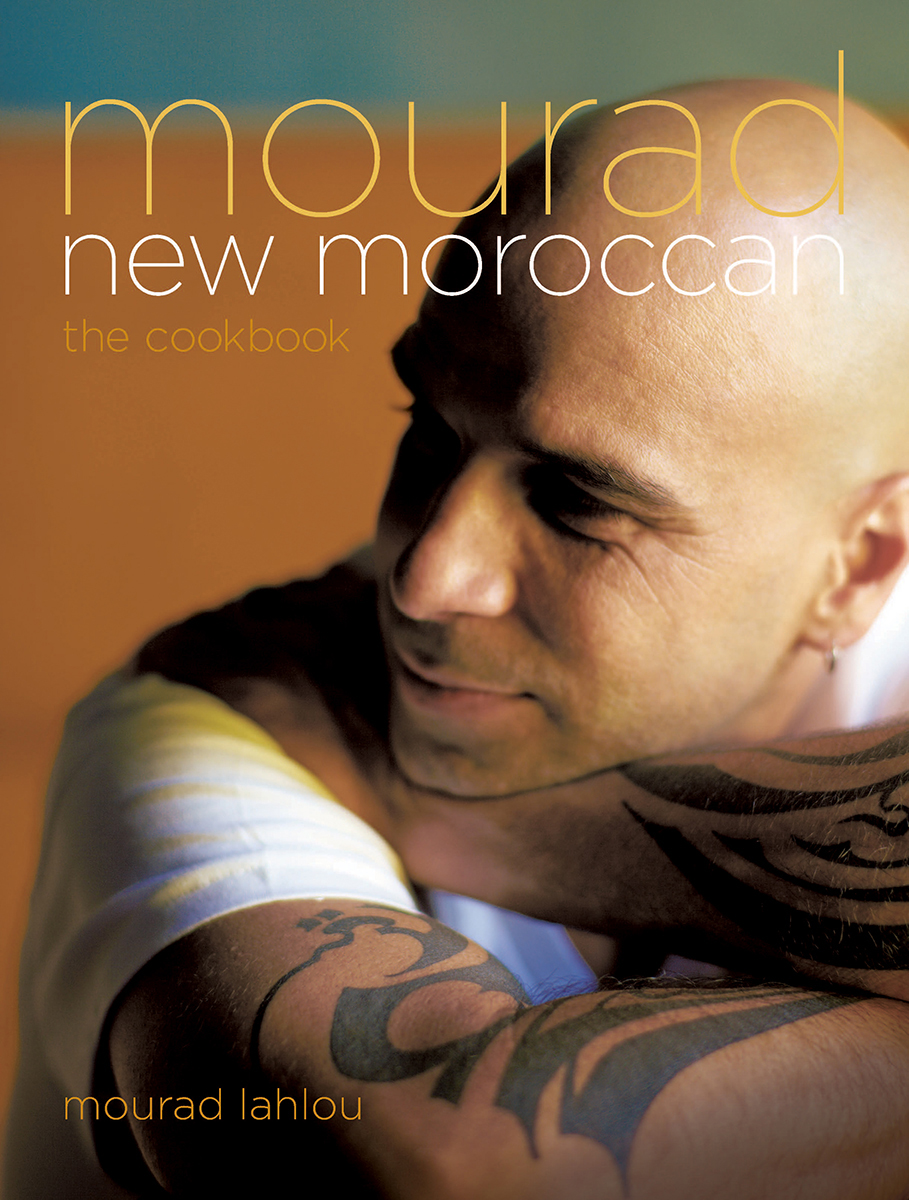

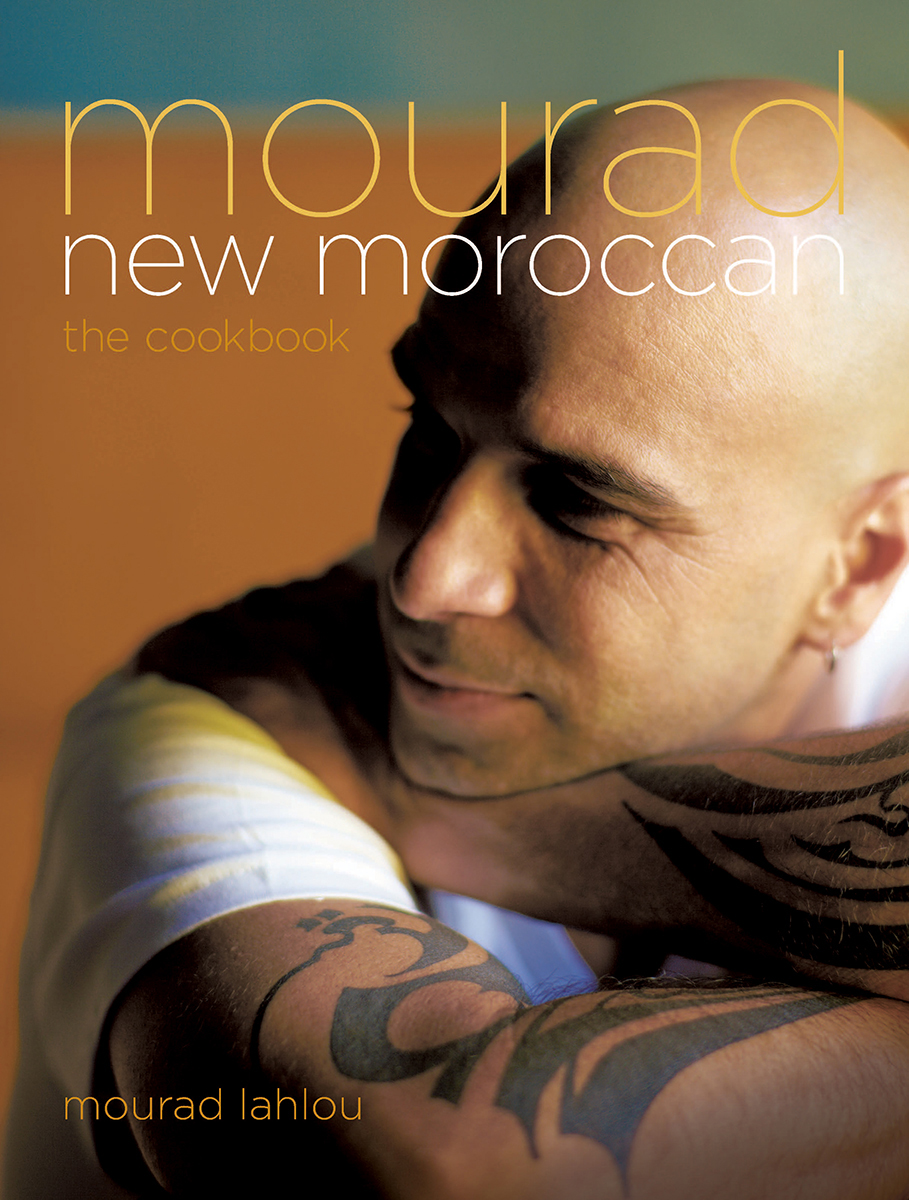

mourad

new moroccan

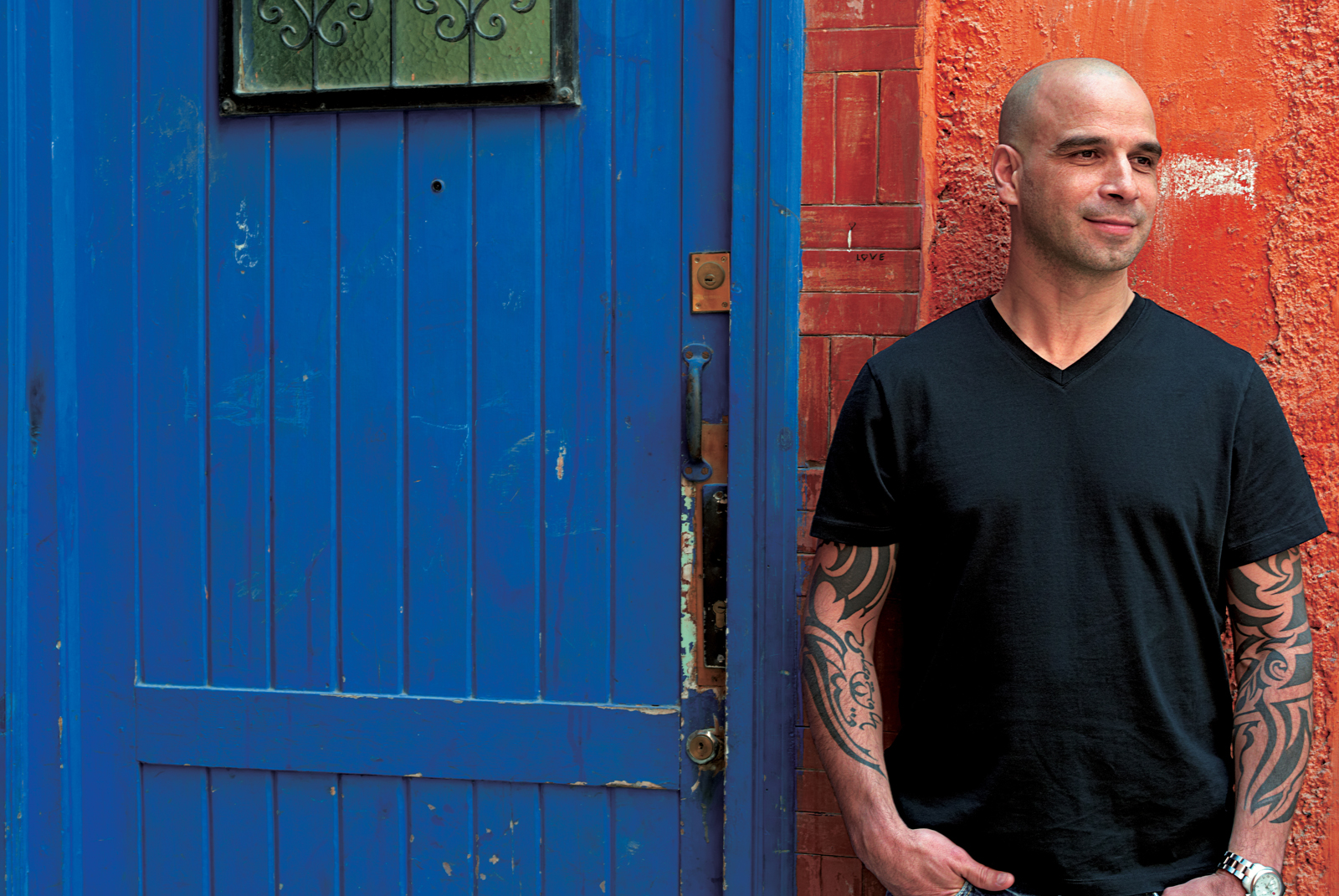

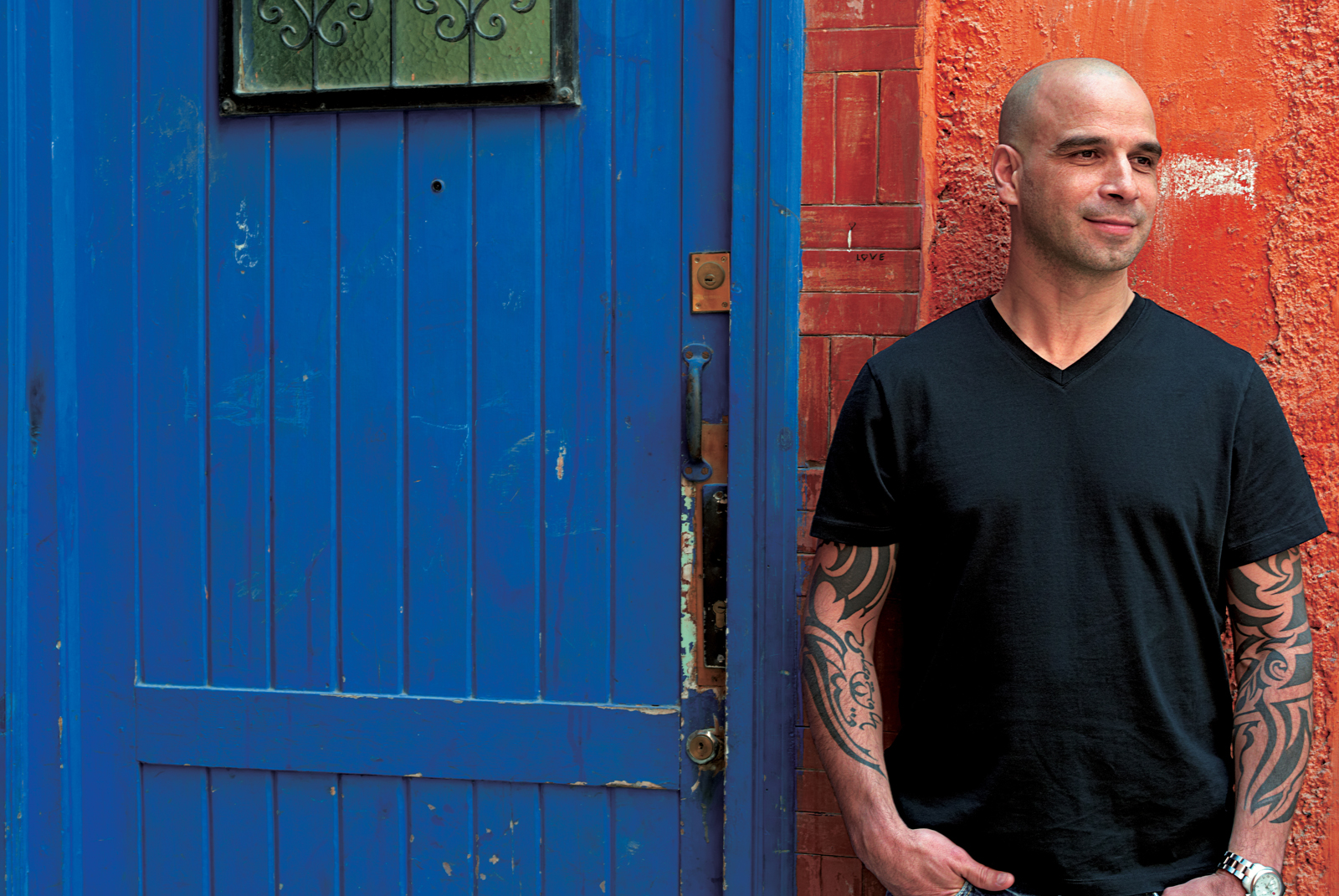

mourad lahlou

With Susie Heller, Steve Siegelman, and Amy Vogler

Photographs by Deborah Jones

To my grandpa, Hajj Ben Seddiq,

still and always, my loving guide, my voice, my values, the barometer of my soul, and the true author of my story

Contents

cooking from memory

Some people set out to learn to cook. They pursue it. They look for teachers. They go to cooking school. They practice and study. I became a cook in a way that could scarcely have been more different from all of that, in a place so far from where I ended up that it feels like a beautiful, brightly colored dream. I learned to cook from memory. Let me tell you how.

I was born in Casablanca. Thats where my dad was from, and my mom had moved there from her native Marrakesh to marry him. But that marriage didnt last, and when my parents split up just a few months after I came along, my mom took my brother and me back to her family homea twenty-room maze of a building on a crooked street in the ancient medina of Marrakesh. From that moment on, my dad vanished from our lives forever, but something else took his place.

In Morocco, family is everything. The idea of a kid growing up with only one parent isnt just a sad matter to cluck your tongue at. Its thought of as a tragedy, and when it happens, people tend to overcompensate. I lost a dad, but when we moved into that beehive of a house, I gained a dozen parentsmy uncles, aunts, great-grandmother, grandmother, and grandfatherwho showered me with attention, love, and praise. And food.

Like most traditional Moroccan houses, ours had two floors, with no windows on the ground floor for privacy. We were neither rich nor poor, but, rather, perfectly comfortable in the sprawling complex that had been in our family for generations and always had a place for whoever needed it. It was built around a light-filled courtyard overlooked by colonnaded balconies, with a large lemon tree in the middle. Upstairs, the bedrooms were grouped somewhat randomly into apartments. Downstairs were three big rooms that opened onto the courtyard: a salon for receiving guests, a family room with a gigantic round table where we ate every meal, and, largest of all, the kitchen.

The kitchen was the spiritual center of the place, but it was all business. Its walls were whitewashed and for the most part unadorned, with a few simple decorations breaking up the expanse: a century-old tagine, now too precious and fragile to use; some rustic spoons hanging from nails; and a photo of a long-gone great-grandmother. A propane stove, a refrigerator, a sink, and a terra-cotta charcoal brazier took up one wall. There were no counters or cupboards, only a couple of shelves to hold pots, pans, spices, and staples.

The real action took place in the middle of the room, at a low round table flanked by a few mismatched chairs. No one ever sat down to eat there. It was the prep table, where the women of the house would sit for hours, working and talking.

From the time I can remember, every day began in exactly the same way. My mom, grandma, some of the aunts, my nanny, and a couple of other women who helped out around the house would get up early and head for the kitchen. Each had her own specialty, and theyd fall sleepily into their morning routine, preparing breakfast, doing laundry, and getting ready for the day ahead without much conversation.

One of them would make the bread for the day, proofing the dough, punching it down, forming it into eight big round loaves, and setting them to proof again on a long board for someone in the family to drop off at the bakery on the way to work or school.

As we stumbled downstairs one by one, wed head to the family room for breakfast. There would be coffee (really more like warm milk with a little coffee in it), bread and olive oil, some kind of porridge, maybe a little leftover hariraMoroccos much-loved lentil and tomato soupor fried eggs with strips of the aged beef called khlea, or perhaps some of my moms famous beghrir pancakes.

And then, when we were all assembled, the ritual would begin. It was like a play that had been running at the same theater for years. A play about a family, with familiar characters and dialoguethe kind of play you could watch over and over, a melodrama with wringing of hands, laughter, and a comfortably predictable story line that always turned out right. It was called Whats for Lunch?

In Morocco, as in much of the world, the midday meal is the main event of the day. Stores, businesses, and schools close at noon, and by 12:30, the entire country is sitting down to a national family meal. Like everywhere else, its a tradition thats eroding, but in the early 70s, it was still an absolute rule.

I would sit on a small chair near the table and watch the characters in our little daily production run through their lines and their choreographyvoices rising with emotion, hands slapping the table, arms folding resolutely over chests.

Grandpa: Sidi Ibrahim has very fine okra now.

Grandma: Okra! We had it yesterday. And the day before. And the day before that. And also last Tuesday. Im tired of it. I never liked it to begin with. Okra.

Grandpa: Ah. How is it you never mentioned this before? Me, when its in season, I could eat it every day. And anyway, next week it will be gone. No more okra. [Clapping his hands silently] We could have it with [dramatic pause] lamb.

One of the aunts (the one with the big job in the fancy office): Please. No lamb. Something lighter that wont make us all fat and sleepy! I cant eat like that every day.

Grandma: You want bland? Thats fine. Eat bland.

An Uncle (the one who has something to do with running the countrys railroads): Chicken, then? The one braised with saffron and crushed tomatoes and okra? Chicken is lighter.

My mom: Not if its that chicken, it isnt. No, well make rice with eggplant.

A plump old aunt:You scrawny girls with your light food! How are you going to get a man with no meat on your bones?

Another uncle (the schoolteacher): Rice is a bore.

Grandma: All right. Rice then. But no eggplant. And definitely no okra!

The grown-ups would argue like this for almost an hour. The kids never said a word, but not for lack of interestat least on my part. My eyes would dart from person to person as I took it all in, learning what it meant to have real, heartfelt convictions about food and life. I could have sat there and listened all day.

At nine oclock, Act 1 of our little breakfast-room drama came to an abrupt conclusion as Grandpa pushed his chair back loudly, grabbed a large straw shopping bag from the back of the door, took my hand, and led me through the courtyard and out onto the street.

Next page