We thank first and foremost the bureau of land Management for their support of research on the Cretaceous of southern Utah, largely as a result of the creation of Grand StaircaseEscalante National Monument in 1996. This includes grants to partner research institutions, support of its own internal research and resource programs, and sponsorship of symposia and publications, including this volume. In particular Marietta Eaton, Carl Rountree, Jeff Jarvis, and Scott Foss need to be called out for their unfailing support.

We thank Glen Canyon Natural History Association and the Grand Staircase-Escalante Partners organizations for their continuous support of research, symposia, and publications. Many thanks are due to Chris Eaton of the former and Daisy Ballard of the latter for the huge roles they played in raising support and helping to proof the volume.

We thank the many authors who attended the 2009 symposium that led to this volume. Their hard work and follow-through with timely submission and editing of the manuscripts were truly inspiring. Along the same lines thanks must also be given to the many reviewers who took time from their busy schedules to ensure that the content is both accurate and current.

Lastly, but certainly not least, we want to recognize the editorial staff at Indiana University Press, including Bob Sloan, Jim Farlow, June Silay, and Karen Hellekson, who agreed to take on this Gordian knot and help make the editors vision for a Utah Cretaceous volume a reality.

The editors

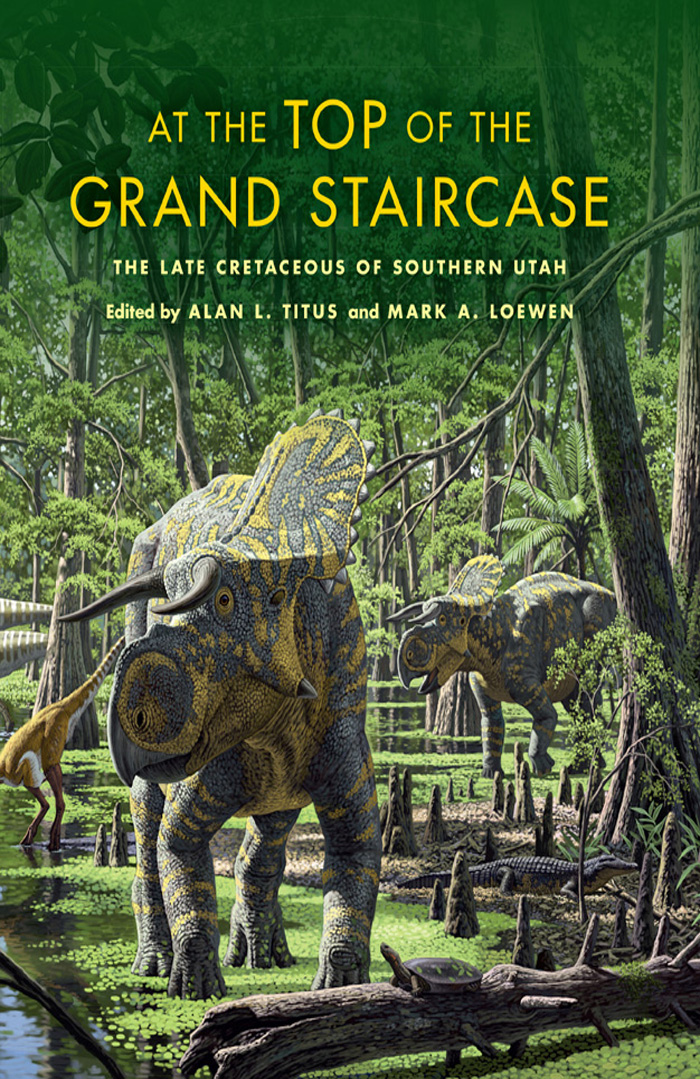

ALAN L. TITUS is Monument Paleontologist at Grand StaircaseEscalante National Monument in Utah and Adjunct Curator, Natural History Museum of Utah.

MARK A. LOEWEN is Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah and Research Associate, Natural History Museum of Utah.

This book was designed by Jamison Cockerham and set in type by Tony Brewer at Indiana University Press, and printed by Sheridan Books, Inc.

The fonts are Electra, designed by William A. Dwiggins in 1935, Frutiger, designed by Adrian Frutiger in 1975, and Futura, designed by Paul Renner in 1927. All were published by Adobe Systems Incorporated.

1

One Hundred Thirty Years of Cretaceous Research in Southern Utah

Alan L. Titus

INTRODUCTION

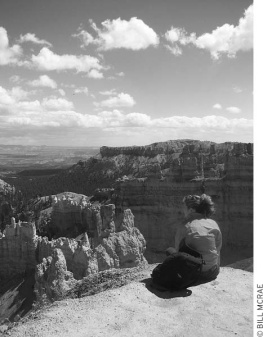

Southern Utah possesses a wild, stark, rugged landscape that leaves most people who experience it irrevocably and profoundly changed. Scenic wonders such as the Grand Canyon, Bryce Canyon (), Zion Canyon, The Wave, Buckskin Gulch, Cedar Breaks, and Capitol Reef are deservedly visited annually by millions of tourists from all over the globe who leave both awestruck and humbled. What is true for the tourist is even more so for the geologists and paleontologists who have worked in the canyon, mesa, plateau, and cliff outcrops of the Grand StaircaseKaiparowits Plateau region ever since the first reports of the Powell expedition were published (e.g., Dutton, 1880; Howell, 1875). But the bedrock geology of the Grand Staircase provides not just the raw material for geomorphological agents to shape renowned scenic wonders; it also contains the fascinating saga of the evolving North American Cordilleran biosphere: a cavalcade of changing landscapes and organisms frozen in time for researchers to poke, prod, and ponder. Even though the area was first geologically mapped over 125 years ago, many basic stratigraphic and paleontological questions still remain unanswered. For vertebrate paleontologists, the region is still a frontier waiting to yield a wealth of data on the Mesozoic biosphere.

Two of the most obvious red rock massifs so sought after by the more aesthetically inclined (the Navajo and Claron formations) are interleaved with thousands of meters of subtler gray and brown strata that comprise southern Utahs Cretaceous record (). Although not as commanding to the eye, the import of this portion of the Grand Staircase story to scientists cannot be overstated: it holds a terrestrial vertebrate fossil record that is certainly the most continuous known in the southern United States, if not the world (Eaton and Cifelli, 1997). As previous scientists probed into the regions Cretaceous geology, it became clear that this portion of the Sevier Foreland Basin was not only a fastidious record keeper of the ecosphere, but also strategically placedclose enough to the orogen to be predominantly terrestrial, but far enough east to maintain at least intermittent contact with the seaway and thus contain crucial high-resolution biostratigraphic data. These conditions persisted until approximately 72 Ma, when Laramide uplifts forced the regression of the seaway into Colorado. Six and a half million years later, the great reign of nonavian dinosaurs was over, leaving a mystery whose solving has become a collective human passion.

GEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS

Powell (1875:190), Howell (1875), and Gilbert (1875) were the first to document beds of Cretaceous Age exposed in what are now known as the Grand Staircase and Kaiparowits Plateau physiographic regions of southern Utah. These works provide only brief descriptions of Cretaceous stratigraphic units, mostly for mapping and summary purposes. It is clear from the geologic maps that accompany these works () that the late 19th-century concept of the regions Cretaceous strata was essentially the same as that today. In his exhaustive monograph, Stanton (1893) concluded from available marine invertebrate fossil evidence that the lower portion of the Cretaceous sequence (Dakota and Tropic formations) was a Colorado Formation equivalent and that the thick overlying succession was terrestrial and Laramie in age.

Twenty-five years passed before any additional serious geologic studies were undertaken in the Kaiparowits region. In 1915 Herbert E. Gregory conducted his first geological reconnaissance in the Kaiparowits, with the intent to document those areas that the Powell expeditions had overlooked or only covered in a cursory way. Gregory returned to the Kaiparowits region in 1918, 1922, 1924, 1925, and 1927 to continue mapping, measuring sections, and making fossil collections. In 1921 the eminent stratigrapher and paleontologist Raymond C. Moore also started stratigraphic and paleontological studies in the region, continuing his efforts into the summer of 1923. The resulting collaborative work between these two researchers (Gregory and Moore, 1931) led to publication of the classic work that established the regions modern nomenclatural framework for Cretaceous strata. With the exception of the lowermost terrestrial portion of the section, which Gregory and Moore (1931) referred to the Dakota (?) Sandstone, the entire Cretaceous section was divided into new formations: in ascending order, they are the Tropic, Straight Cliffs, Wahweap, and Kaiparowits. Although placement of some of the contacts between these units has changed slightly, with the exception of the Dakota Formation, which has now been partly replaced with the Cedar Mountain Formation, Gregory and Moores original names and concepts are used today essentially unchanged.