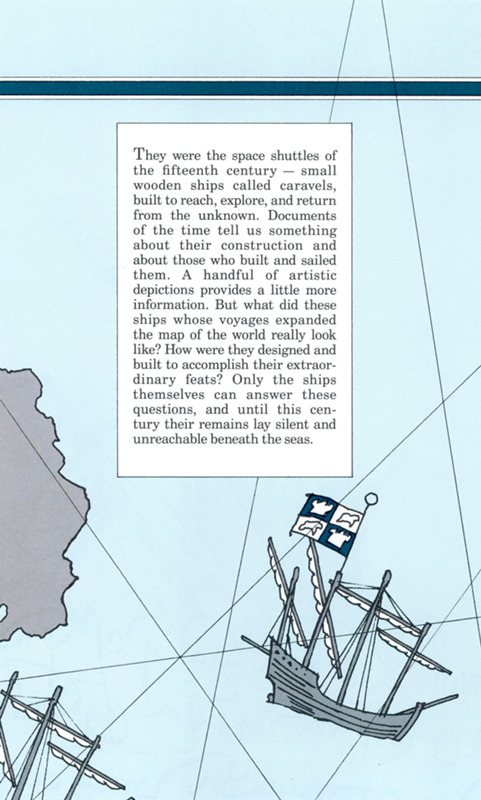

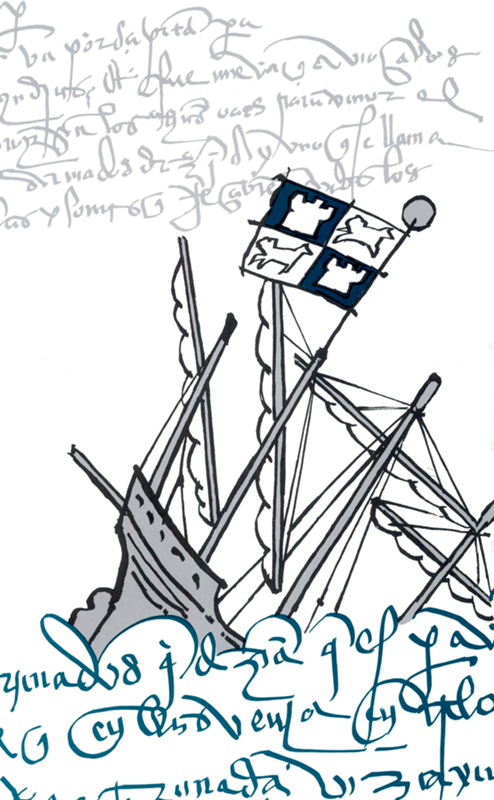

They were the space shuttles of the fifteenth centurysmall, wooden ships called caravels, built to reach, explore, and return from the unknown. Documents of the time tell us something about their construction and about those who built and sailed them. A handful of artistic depictions provides a little more information. But what did these ships whose voyages expanded the map of the world really look like? How were they designed and built to accomplish their extraordinary feats? Only the ships themselves can answer these questions, and until this century their remains lay silent and unreachable beneath the seas.

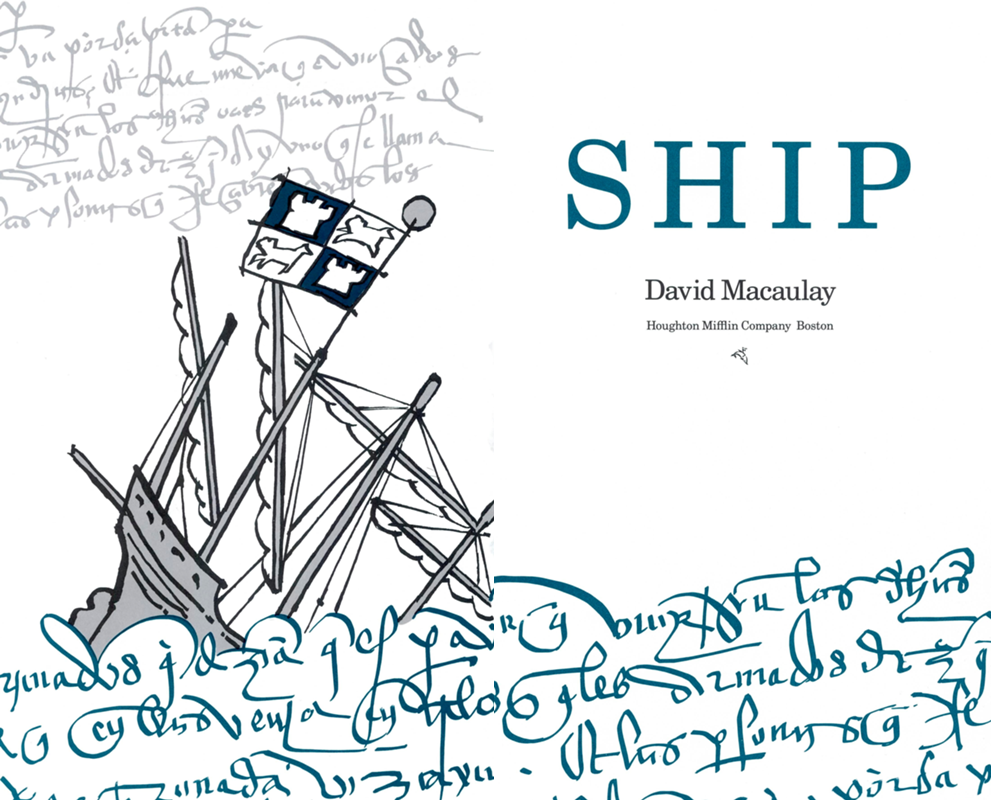

SHIP

David Macaulay

Houghton Mifflin Company Boston

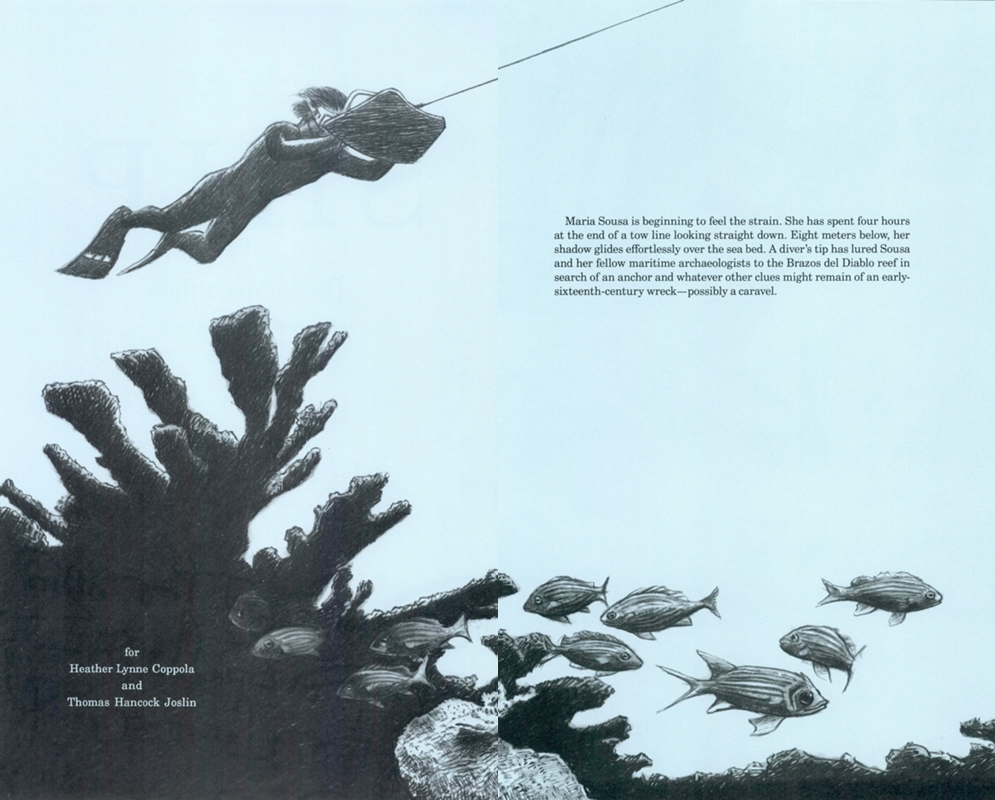

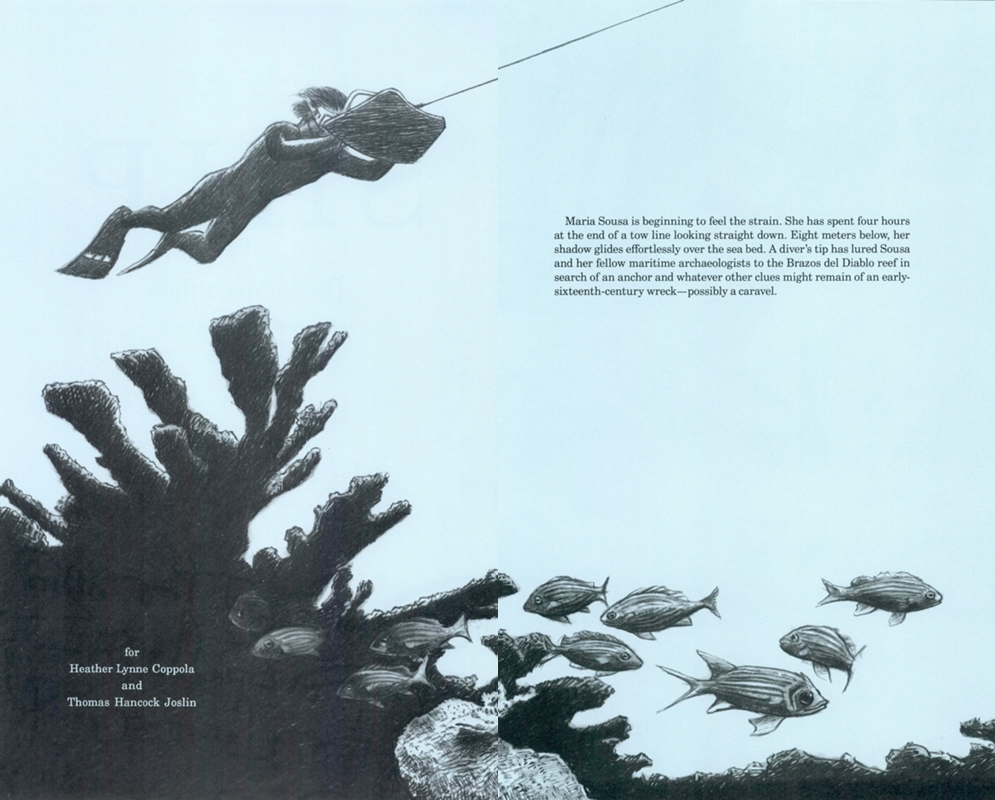

for

Heather Lynne Coppola

and

Thomas Hancock Joslin

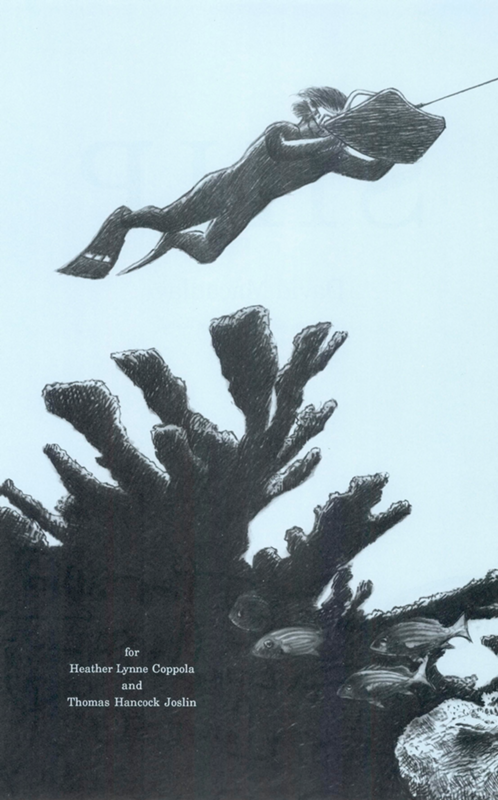

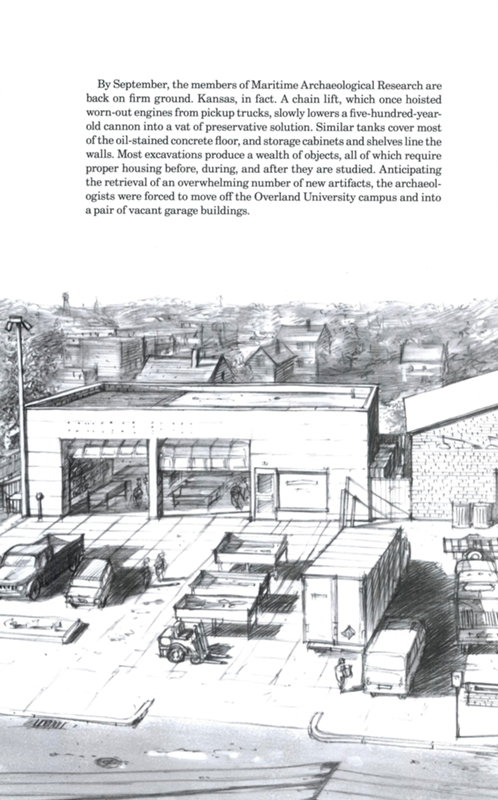

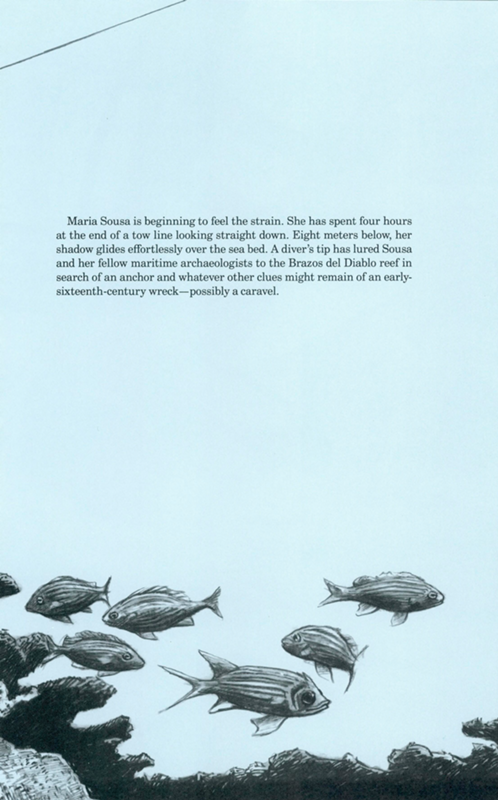

Maria Sousa is beginning to feel the strain. She has spent four hours at the end of a tow line looking straight down. Eight meters below, her shadow glides effortlessly over the sea bed. A diver's tip has lured Sousa and her fellow maritime archaeologists to the Brazos del Diablo reef in search of an anchor and whatever other clues might remain of an early-sixteenth-century wreckpossibly a caravel.

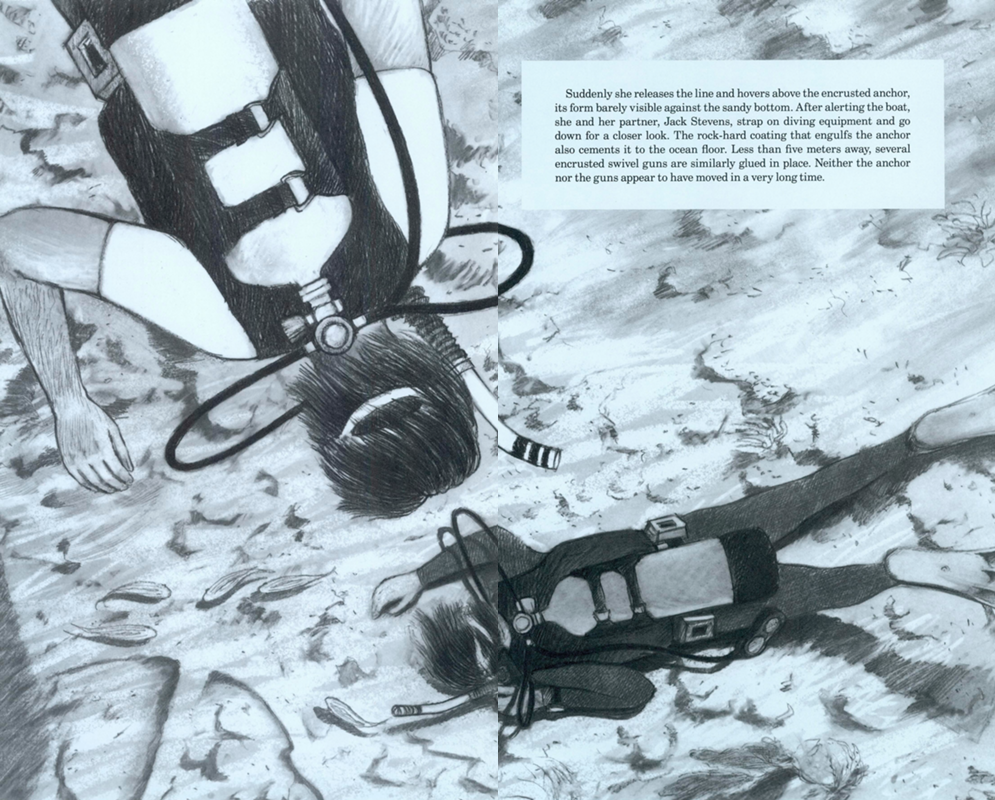

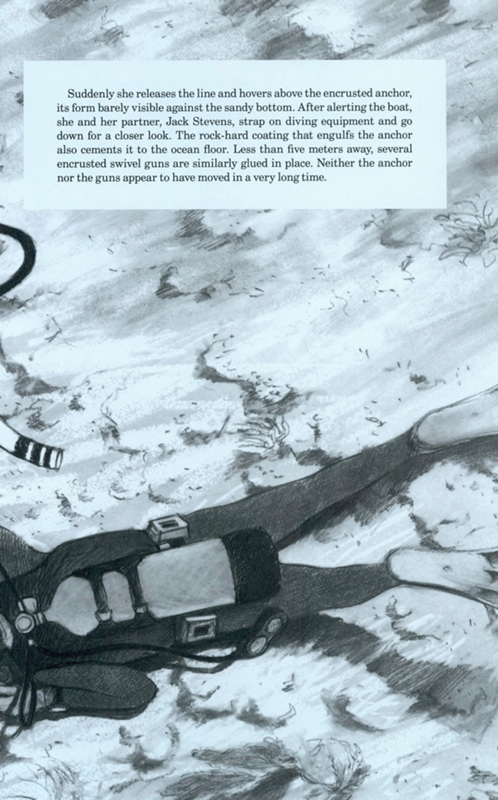

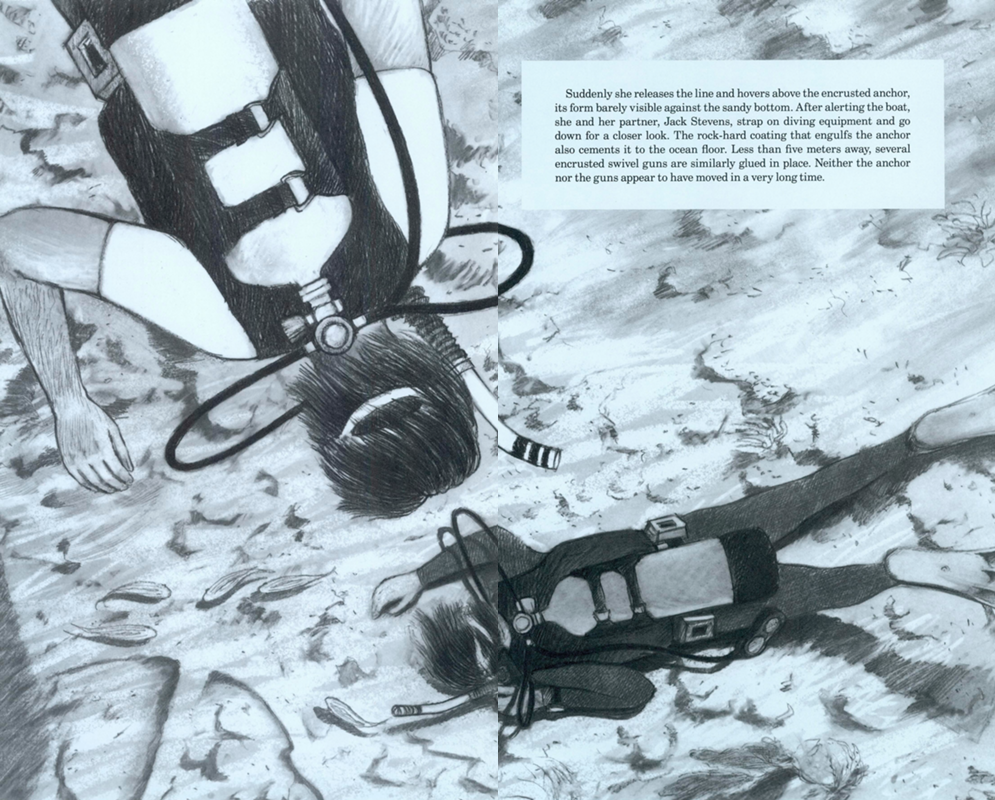

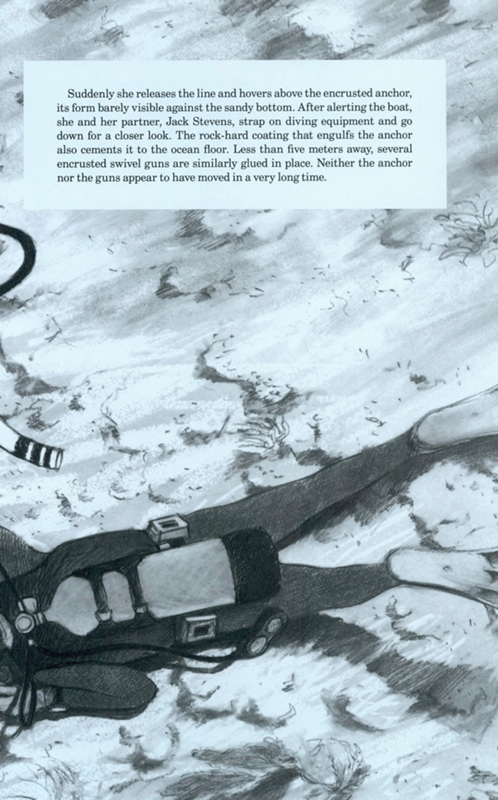

Suddenly she releases the line and hovers above the encrusted anchor, its form barely visible against the sandy bottom. After alerting the boat, she and her partner, Jack Stevens, strap on diving equipment and go down for a closer look. The rock-hard coating that engulfs the anchor also cements it to the ocean floor. Less than five meters away, several encrusted swivel guns are similarly glued in place. Neither the anchor nor the guns appear to have moved in a very long time.

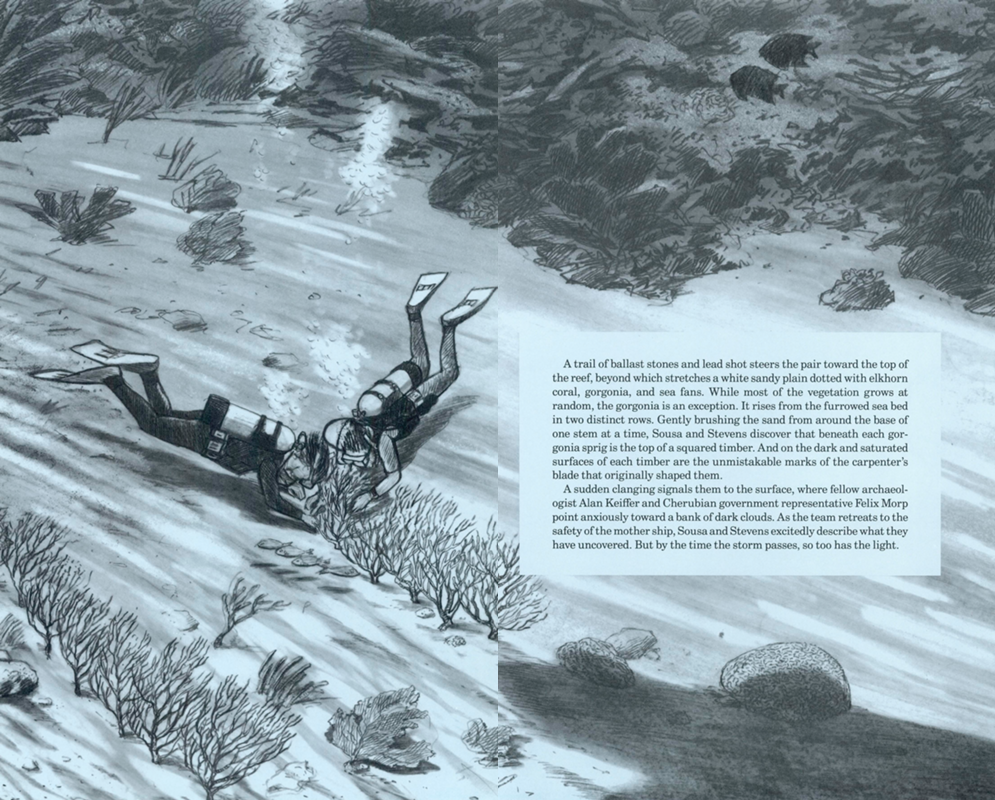

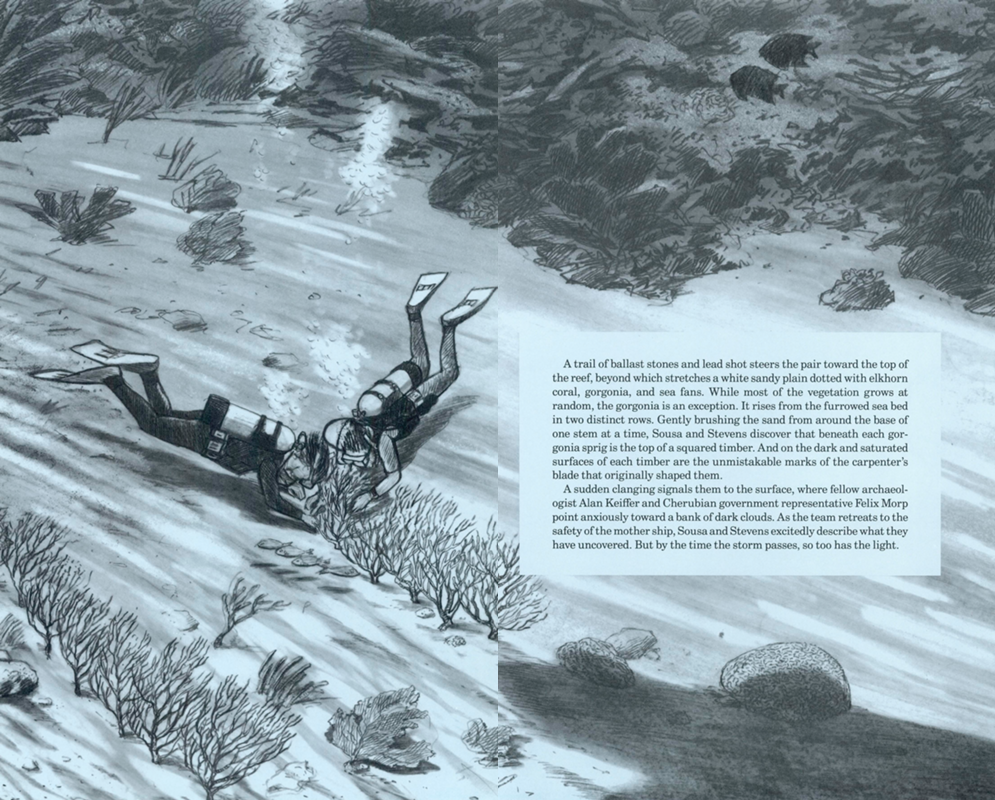

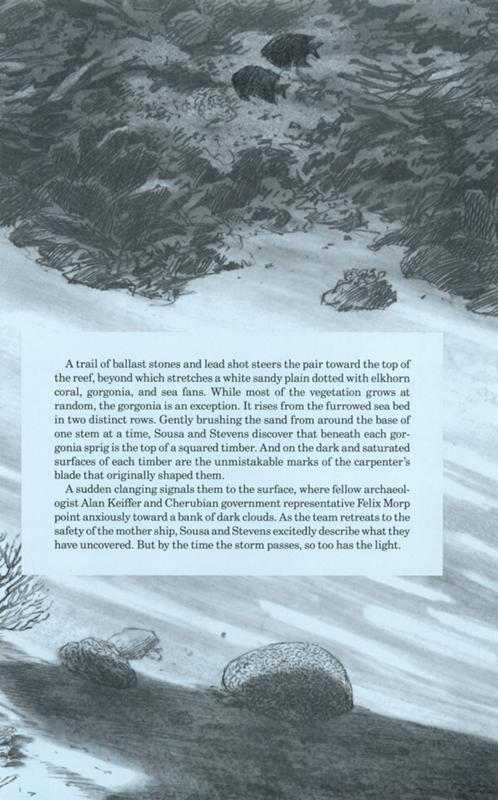

A trail of ballast stones and lead shot steers the pair toward the top of the reef, beyond which stretches a white sandy plain dotted with elkhorn coral, gorgonia, and sea fans. While most of the vegetation grows at random, the gorgonia is an exception. It rises from the furrowed sea bed in two distinct rows. Gently brushing the sand from around the base of one stem at a time, Sousa and Stevens discover that beneath each gorgonia sprig is the top of a squared timber. And on the dark and saturated surfaces of each timber are the unmistakable marks of the carpenter's blade that originally shaped them.

A sudden clanging signals them to the surface, where fellow archaeologist Alan Keiffer and Cherubian government representative Felix Morp point anxiously toward a bank of dark clouds. As the team retreats to the safety of the mother ship, Sousa and Stevens excitedly describe what they have uncovered. But by the time the storm passes, so too has the light.

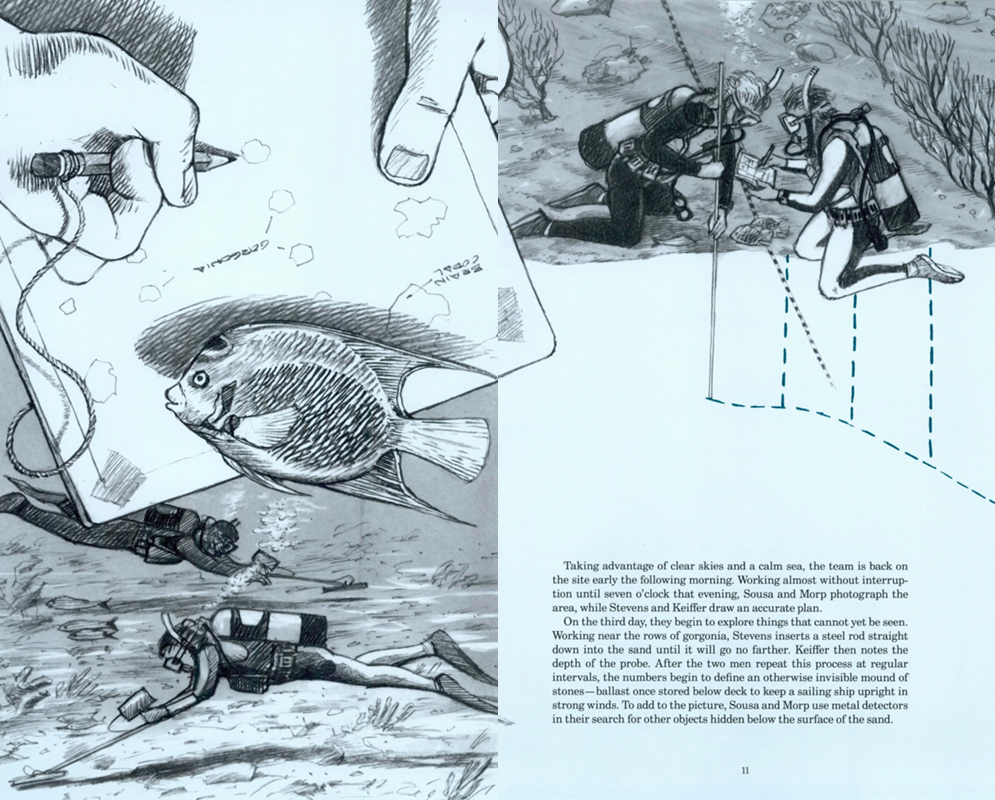

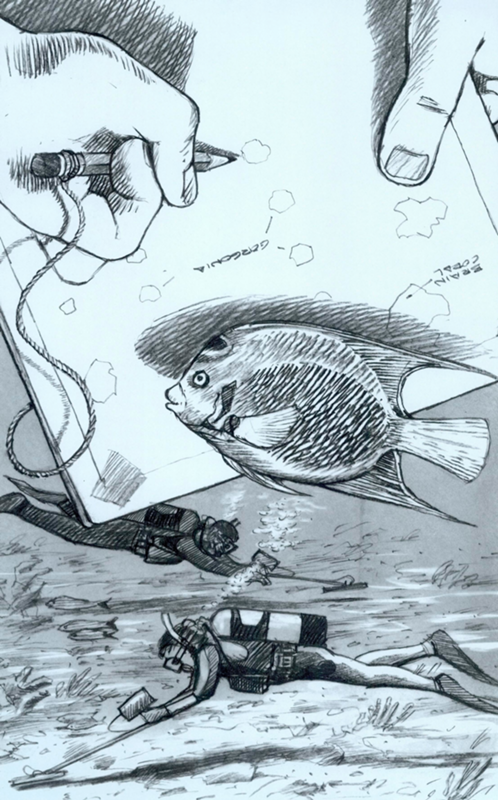

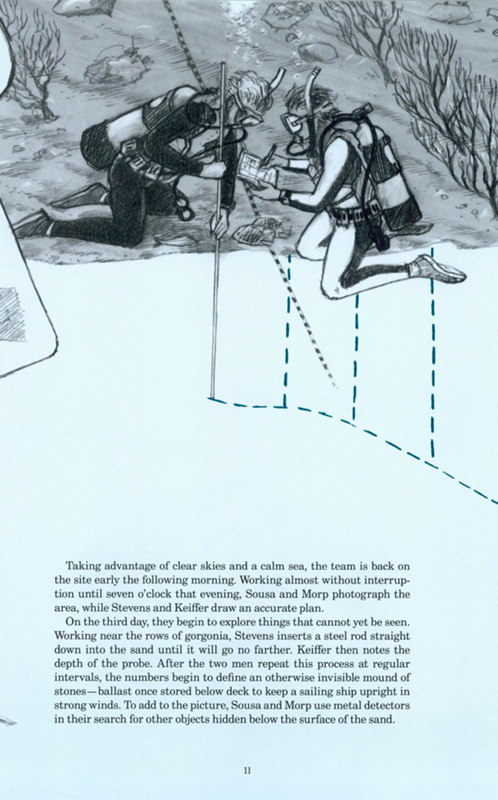

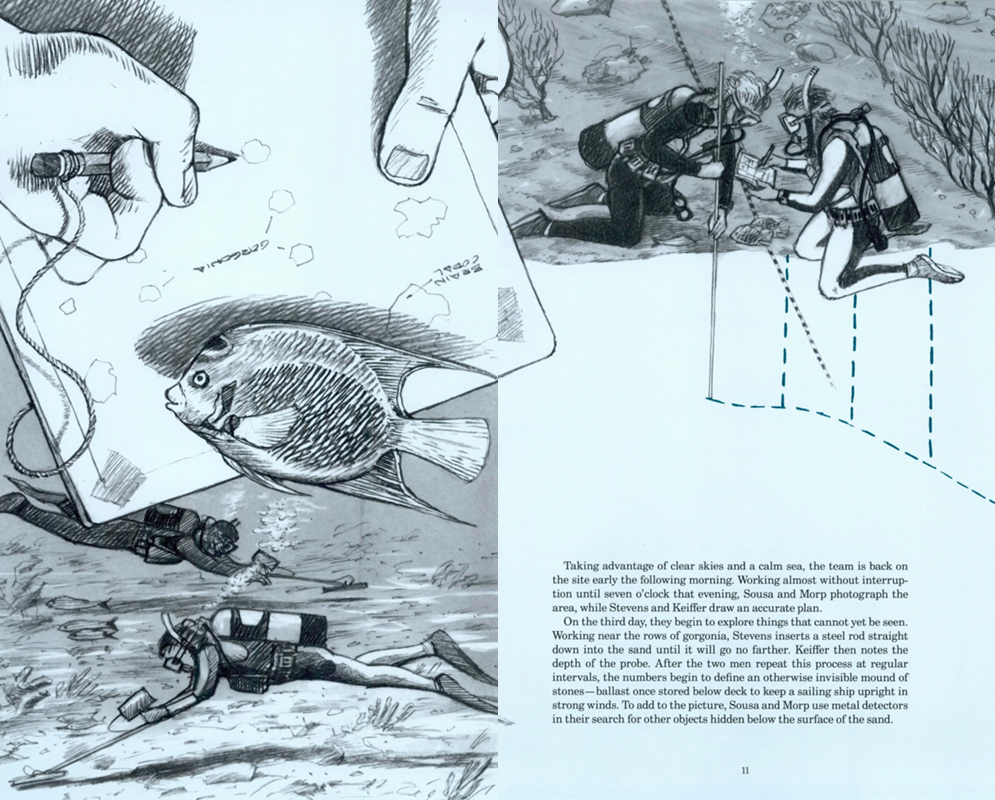

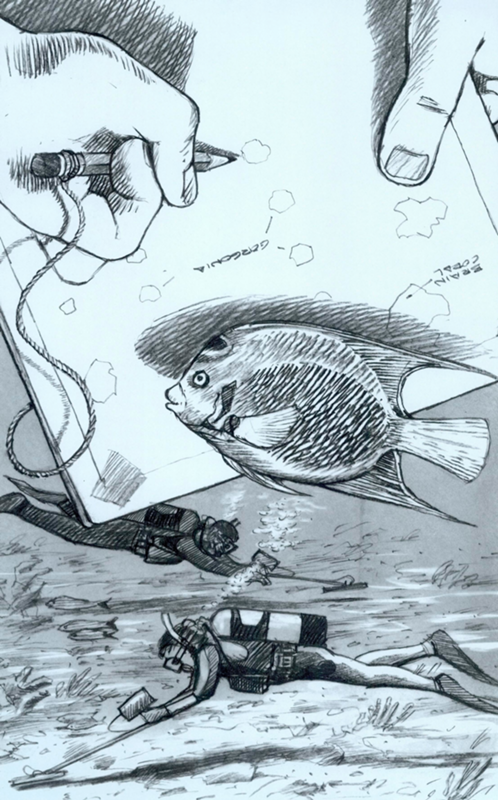

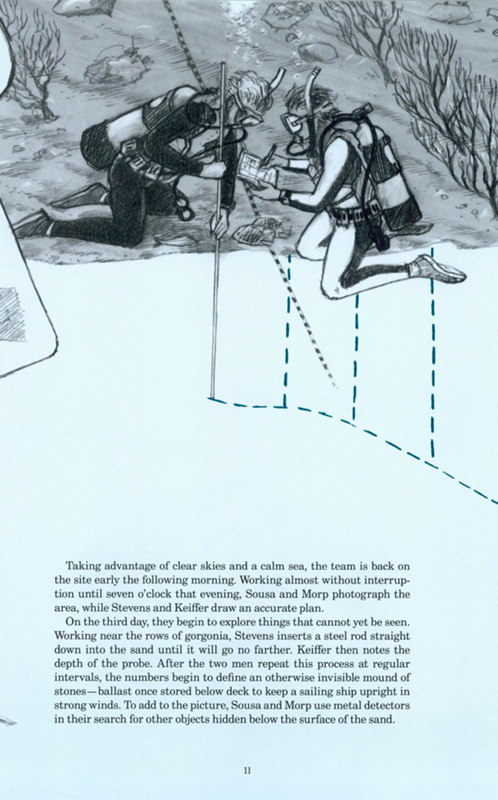

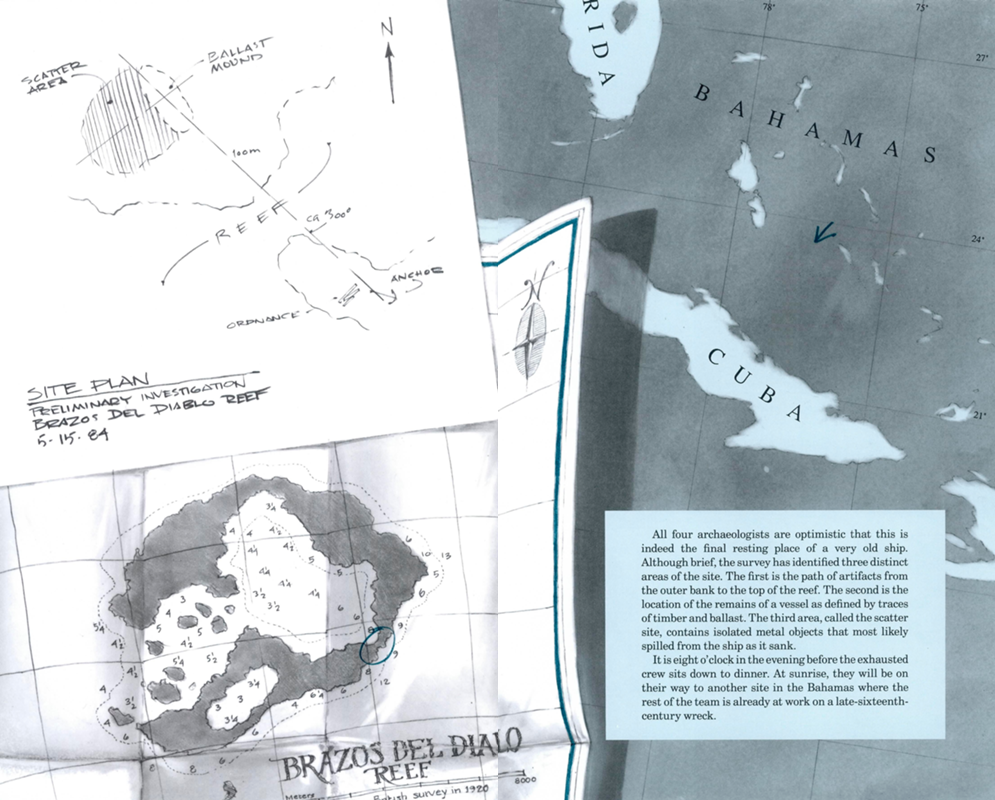

Taking advantage of clear skies and a calm sea, the team is back on the site early the following morning. Working almost without interruption until seven o'clock that evening, Sousa and Morp photograph the area, while Stevens and Keiffer draw an accurate plan.

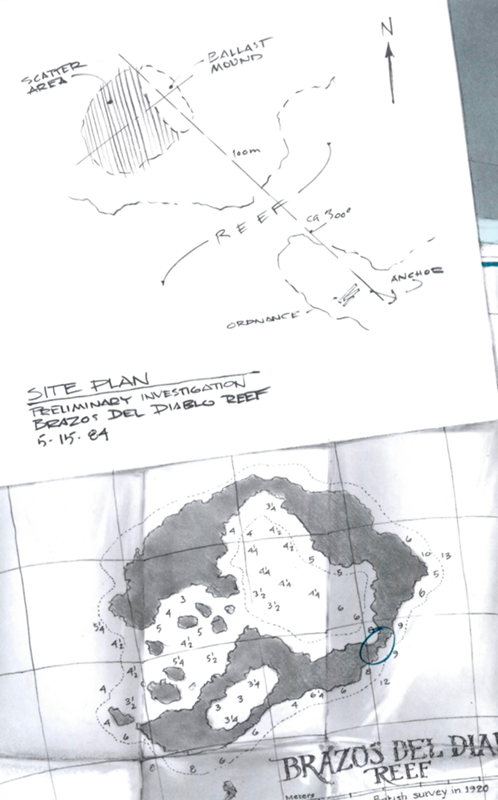

On the third day, they begin to explore things that cannot yet be seen. Working near the rows of gorgonia, Stevens inserts a steel rod straight down into the sand until it will go no farther. Keiffer then notes the depth of the probe. After the two men repeat this process at regular intervals, the numbers begin to define an otherwise invisible mound of stonesballast once stored below deck to keep a sailing ship upright in strong winds. To add to the picture, Sousa and Morp use metal detectors in their search for other objects hidden below the surface of the sand.

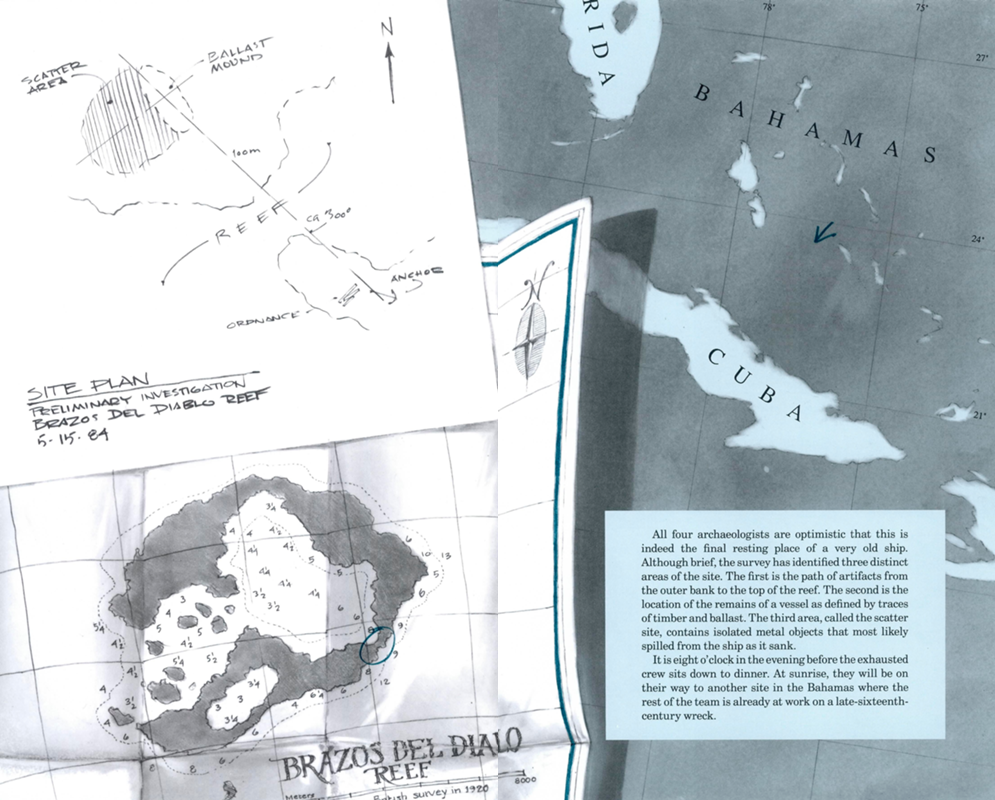

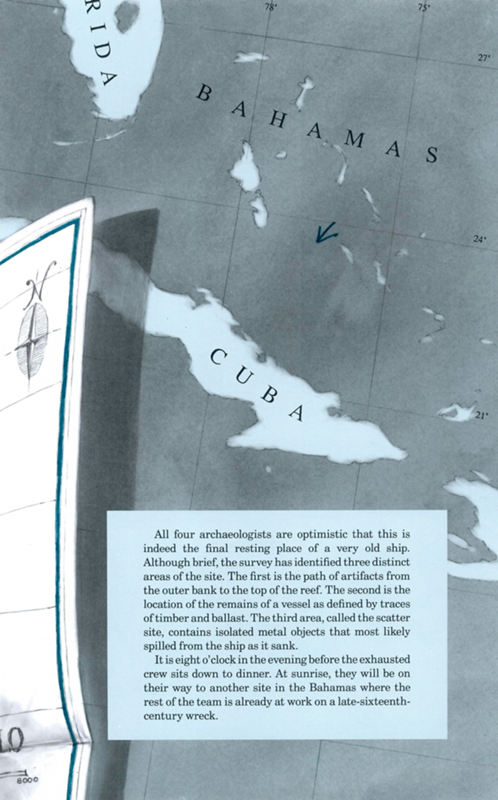

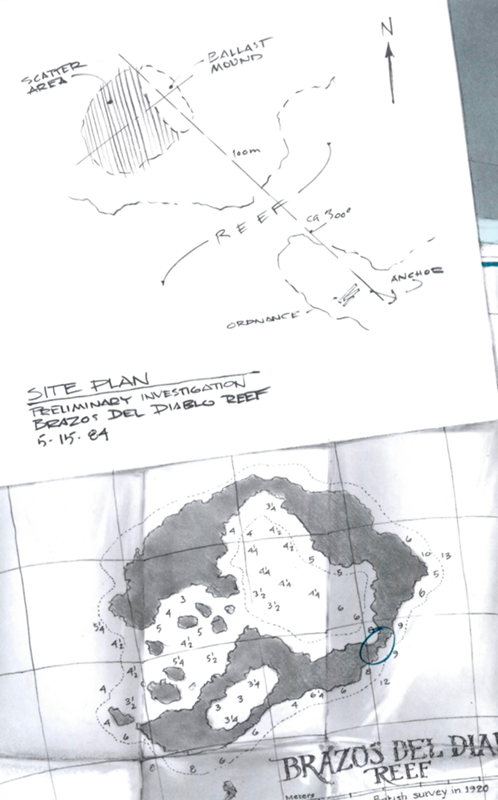

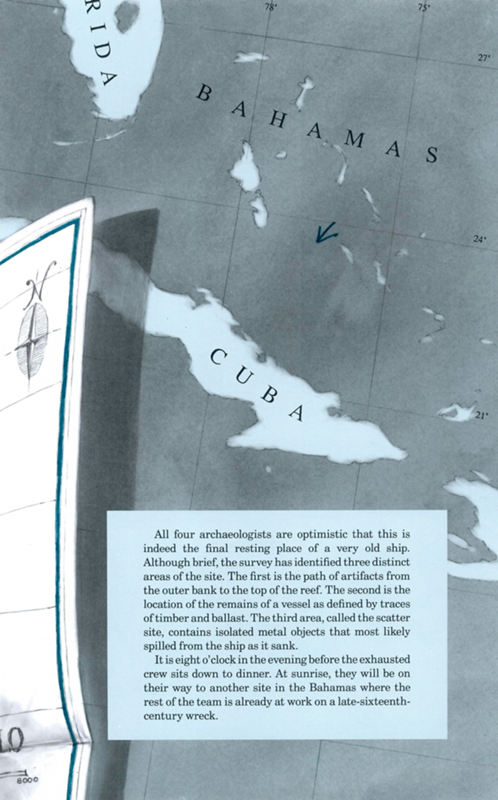

All four archaeologists are optimistic that this is indeed the final resting place of a very old ship. Although brief, the survey has identified three distinct areas of the site. The first is the path of artifacts from the outer bank to the top of the reef. The second is the location of the remains of a vessel as defined by traces of timber and ballast. The third area, called the scatter site, contains isolated metal objects that most likely spilled from the ship as it sank.

It is eight o'clock in the evening before the exhausted crew sits down to dinner. At sunrise, they will be on their way to another site in the Bahamas where the rest of the team is already at work on a late-sixteenth-century wreck.

Next page