ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank: Yuny Parada, who offered guidance and images and told me I must write this book, then helped me throughout; Daisy Chilin for her assistance in whatever task was necessary; and Inez Yslas, who helped with technical coordination and phone calls. The following individuals shared knowledge and their life experiences: Paul Ayers, Stacy Camp, Dr. Daniel Castro, Don Chaput, Lisa Derderian, Dr. Lynne Emery, Juanita Espino, Serafin Espinoza, Delfina Esquivel, Daniel Estrada, Vanessa Flores, Elias Galvan, Catherine Haskett Hany, Michael Heralda, Lilia Hernndez, Maria Luisa Isenberg, Steve Lamb, firefighter Victor Laveaga, Abel Lopez, Lorraine Lopez, Felipe Agredano Lozano, Michaela Mares, Ed Maya, Gregory McReynolds, Roger Mejia, Robert Monzon, Elizabeth Pomeroy, Janet Pope-Givens, Abel Ramirez, Joe Robledo, Julie Chavez Rodriguez, Nicholas Rodriguez, Raul R. Rodriguez, Dave Ruiz, Paul Secord, Belen Lopez Segura, Capt. Dan Serna of the Pasadena Fire Department, Bruce Smith, Luis Torres, Chester King User, Mauricio Valadez, Maxine Garcia Wardell, and Marge Wyatt.

I also want to thank Gamble House director Ted Bosley; Huntington Librarys Jennifer Watts and Erin Chase; Los Encinos State Historical Parks Michael Crosby; Pasadena Museum of Historys Jeannette OMalley, as well as Laura Verlaque and Kirk Meyers, Bob Bennett, Sid Gally, George Hiyakawa, Julie Stires, and Carol Watson; Pasadena Police Departments acting chief, Christopher Vicino, as well as officer Victor Cass and Susana Castro; Pasadena Public Librarys Jan Sanders and executive director Dan Mclaughlin; Kelly Sutherlin McLeod and Michelle Rueda; Institute for the Study of the American West, including Marva Felchlin, Kim Walters, and Liza Posas; and University of Southern California Digital Archives Los Angeles and Southern California History and Special Collections, particularly Dace Taub and Rachelle Balinas Smith. Thanks must go to the scholarly work and previous volumes by Francisco Balderrama, William Deverell, Marguerite Duncan-Abrams, Michael James, Robert H. Peterson, Manuel Pineda, Ann Scheid, and Michelle Zack.

Special appreciation goes to Ed and Rita Almanza, Brian Biery at www.brianbiery.com , James M. Grimes and Mark Humphrey at www.humphreyphotography.com , and J. Michael Walker at www.jmichaelwalker.com for image use.

Pat and Rosalina Guerrero and Yvonne Ruiz deserve special thanks for working well out of the limelight because they believed stories must be shared. A special thanks to the members of the Pasadena Mexican American History Association, who shared their life stories, trusting that we would honor their gift. On a very personal note, I want to thank the kiddoes near and far, Matt, Kate, Matthew, Lili, and Celi, for loving me and respecting my work. And finally, thanks to the love of my life, James Grimes, who is always there with his advice, grammatical opinion, and love.

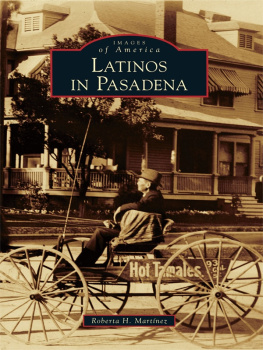

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

RAICES Y RAMAS

In 1492, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain made an effort, in concert with the Spanish Inquisition, to consolidate their kingdom, establish colonies, and convert their subjects to Roman Catholicism. The era of the acceptance of multiple religionsMuslim, Catholic, and Jewin the Iberian Peninsula had ended. Those who left Spain represented the religious and cultural communities that had lived together for five centuries and had preceded Ferdinand and Isabellas ascendancy. Colonizing Nueva Espaa was of paramount importance. Pedro Alonso Nio, of African heritage, served as navigator for Christopher Columbus. For the next three centuries, colonies were established and the social system that developed was complex, based on geographic origin, socioeconomics, and the ethnic lineage of parents. There were as many as 16 different social stations or castas. Penisulares , those born on the Iberian Peninsula, were most powerful. Criollos , born in America, their parents born in Spain, could not attain the same level of position because of their place of birth. Casta paintings visually expressed these distinctions. They served as both news service and social delineators, clearly defining position and status. There were many unions that existed in Latin America; the mestizos, of Spanish and Mesoamerican heritage, and the mulatto, of Spanish and African heritage, were most common. Many Africans were brought as slaves from Africa, the earliest recorded in the 16th century. The incursion of the Spanish into Maya and Mexica territories were also a part of this era. While this was taking place in Nueva Espaa, the Tongva of what is now Southern California lived in clans and settlements, trading among themselves and others, from what we know as the San Gabriel Mountains to Catalina Island. Sufficiency and sustainability were maintained by group size and knowledge of animal, land, and sea. Chants, dance, drawings, and songs were a part of the culture that was shared by those appointed as culture bearers.

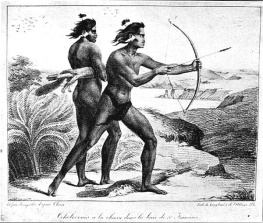

The Tongva lived in as many as 30 to 40 areas in the San Gabriel and San Fernando Valleys. Their work and roles were based primarily along gender lines: women gathered and cooked, and men fished and hunted. Each worked on tasks that supported their main workbasket weaving for women, net-working for men. They traveled by foot or by tiats (canoes). According to Dr. Rosanne Welch, those who were most successful as artisans, hunters, or traders were at the top of the hierarchical structure. Families of long lineage, of past contribution to the tribe, were at the next level. The third group was the remainder of the population. Chiefs, based on blood lineage, could be male or female. Primary sources for our knowledge of their culture were Bartolomea de Comcrabit and Narcissas Higuera, both Tongva. With the establishment of the missions, many natives were absorbed or enveloped by the culture of Nueva Espaa . Nearly 6,000 Tongva lie buried in the grounds of the Misin San Gabriel. Among those buried may be Prospero, who was at the mission in 1804. He was given, or took, the last name Dominguez. With the secularization of lands, records were lost or not kept. Members of the Tongva nation are currently investigating and reconstructing their culture and searching for relatives who were absorbed into the society of Nueva Espaa. (Chester King User.)

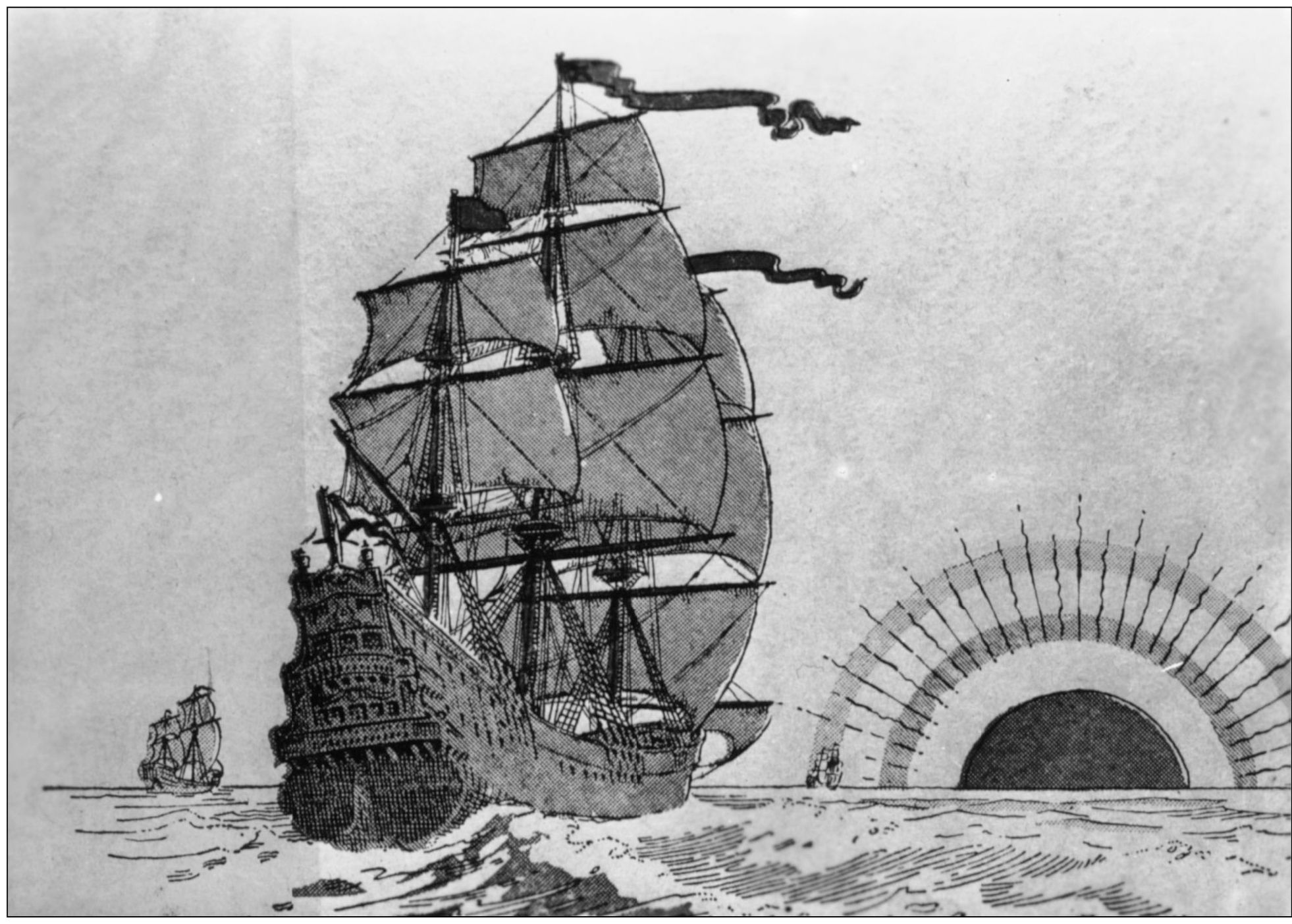

For over two centuries, the Manila-Acapulco galleons were the spice line for trade whose cargo included porcelain, processed silk cloth, and silver. With the trade came interaction among groups of people. Dances, diseases, food, language, and musical and visual arts were all a part of the exchange that took place at a more informal level. European Baroque music informed the music that followed. Elements of the mariachis instrumentation, the practice of Decima in the Yucatan, and call and response from Africa are remnants of the trading and traveling that took place. Sailors and others were known to arrive at port and not return to ship. Music and art forms were shared, and new words were added to vocabularies; Asia and Europe became connected. The regular trips ended following Mexican Independence in 1822. (University of Southern California, USC Special Collections.)