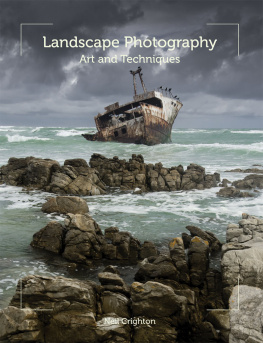

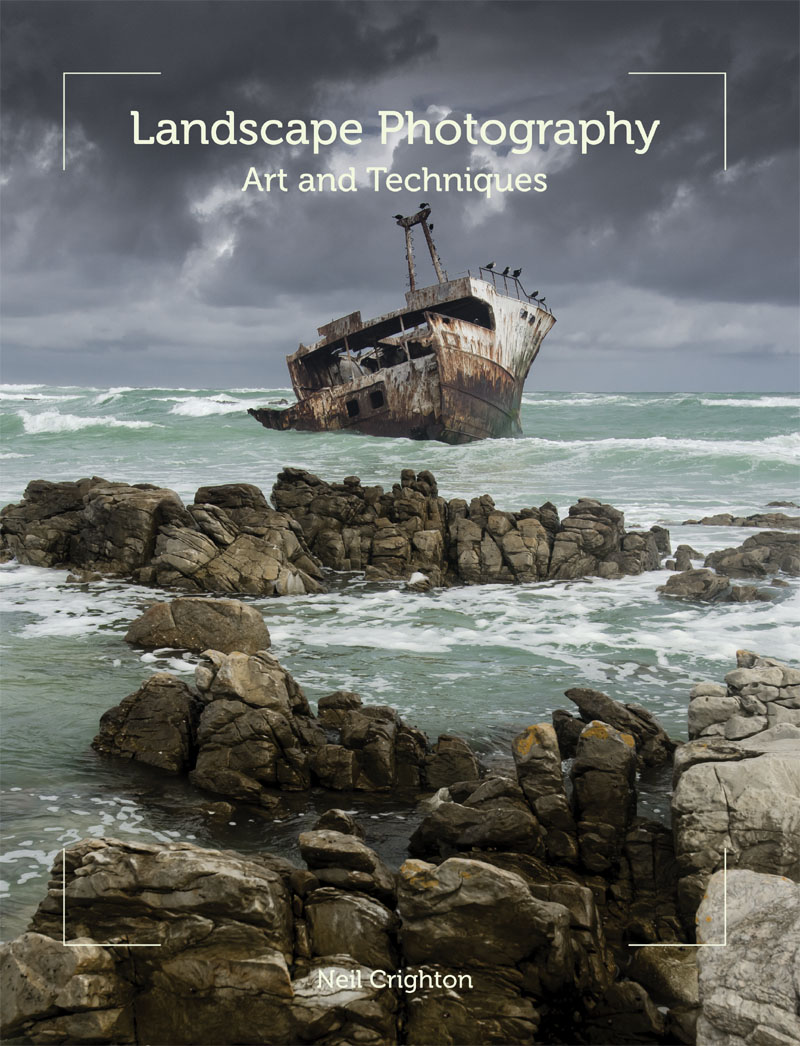

Landscape Photography

Art and Techniques

Neil Crighton

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2012 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

Neil Crighton 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781847978486

Acknowledgements

In writing this book, I am sharing with you the experience I have gained in my career as a photographer and lecturer that has so far lasted 42 years. I consider myself lucky to have had the opportunity to visit and experience some of the wonderful locations around the world and meet some fascinating and inspiring people on my journey.

My appreciation for additional photos goes to Enrique Fernandez Redo, Andreas Fernandez Rosenke, Nina Fernandez Rosenke, Alasdair Crighton and Julia Crighton and for their generosity in making them available to me.

None of this would have been possible without the support of my wife Julia, for her painstaking editing and assistance, and our children, Fraser, Beatrice and Alasdair, who waved me off on my journeys and never complained about my long absences away from home. Thank you.

Contents

Winter moon.

Foreword

T wo of the most frustrated trades are dentists and photographers, Picasso once said. Dentists because they want to be doctors, and photographers because they want to be painters.

Like all good aphorisms, this is completely bogus. The painter himself didnt believe it. The inspiration for Cubism arguably came from some distorted images taken on his friend Severinis broken camera and, in any case, Picasso also announced: I have discovered photography. Now I can kill myself. I have nothing else to learn.

Discoverers of Neil Crightons work in the generously illustrated pages of this important new volume will not be rushing to follow Picassos lead. For one thing, we have plenty to learn and this is just the book to teach and inspire us.

This is much more than a how-to manual. In his engaging introduction, Neil traces the line of descent of landscape art to its early fifteenth-century origins, and the early croszcfertilization of art and photography with camera obscura and lucida a glass prism on an adjustable metal arm fastened to the artists drawing board, which refracted a traceable image on paper.

There was the usual grumbling about photography killing art, of course (just as video would kill the radio star, and Kindle the printed book). Charles Baudelaire, reviewing an 1859 photographic exhibition said:

If photography is allowed to supplement art, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether.... If it is allowed to encroach upon the domain of the... imaginary, upon anything whose value depends solely upon the addition of something of a mans soul, then it will be so much the worse for us.

A flick through some of the extraordinarily atmospheric photographs in this book shows how misplaced these fears were.

Far from being a frustrated painter, Neils photographic calling came early. His own personal development grew from school science lessons for me, the whole magical process of photography then was a continuation of the study of chemistry and chemical reactions applied to a creative purpose to experiments with his fathers 35mm Kodak Coloursnap, a secondhand Zenit, and a prized Asahi Pentax SV.

Usefully for any photographer hoping to make a living from the business, his own career route, from positions with the National Physical Laboratory and Portsmouth Polytechnic, to a globetrotting role with ICI/Zeneca took him to fifty-six countries, and ultimately to his own business. He now lives with his wife Julia in northern Sweden, where he has converted an old church into a photographic gallery and school of photography.

Throughout, Neils infectious enthusiasm and passion for his subject, and his subjects, shines through. Enjoy.

Richard Lomax,

Journalist and Director:

Redhouse Lane Communications Ltd.

(London and Glasgow)

View of Stockholm through a window.

Introduction

P ainters began to include nature in their work during the fourteenth century, introducing elements of the landscape as the background setting for the figures in their paintings, which were invariably religious commissions depicting important religious figures or biblical characters in an allegorical setting.

Landscape painting was established as a genre in Europe early in the fifteenth century, portrayed as a setting for human activity, yet still often expressed within a religious context. Landscapes were idealized, mostly reflecting a pastoral ideal drawn from classical poetry which was first fully expressed by Giorgione and the young Titian, and remained associated above all with a hilly wooded Italian landscape, depicted by artists from Northern Europe, many of whom had never visited Italy. Joachim Patinir developed a style of panoramic landscapes with a high viewpoint that remained influential for a century, and was further used by Pieter Brueghel the Elder. The Italian development of graphical perspective allowed large and complex views to be painted very effectively.

The term landscape was not used until the sixteenth century. It was borrowed from the Dutch painters term landschap, meaning region, or tract of land, but when brought into the English language it had acquired a newer artistic sense as a picture depicting scenery on land. The seventeenth century saw the dramatic growth of landscape painting, particularly in the Netherlands, in which extremely realistic techniques were developed for depicting light and weather.

In England landscape painting was considered a minor branch of art until the late eighteenth century, when the Romantic spirit encouraged artists to raise the profile of landscape painting. William Turner, known as the painter of light, employed watercolour landscape painting techniques to his use of oil paints to create a unique style of light and atmosphere for his land- and seascapes. Initially he toured England and Scotland, and later in his career travelled widely in Europe to Germany, Holland, Belgium, France, Italy and Switzerland.

Turners Romantic style gradually gave way to a style that was to become even more widely recognized, developed by the French. From the 1830s Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and other painters in the Barbizon school established a landscape tradition that would become the most influential in Europe for a century, with the impressionists and post-impressionists making landscape painting for the first time the main source of general stylistic innovation across all types of painting.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE CAMERA

The artist David Hockney and physicist Charles M. Falco have suggested that advances in realism and accuracy in painting and drawings in western art were primarily the result of optical aids such as the camera obscura, camera lucida, and curved mirrors, rather than solely due the development of artistic technique and skill.