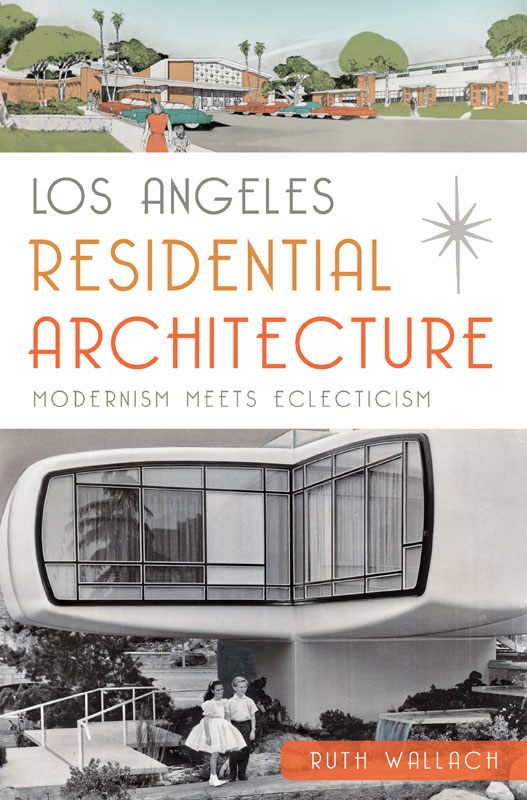

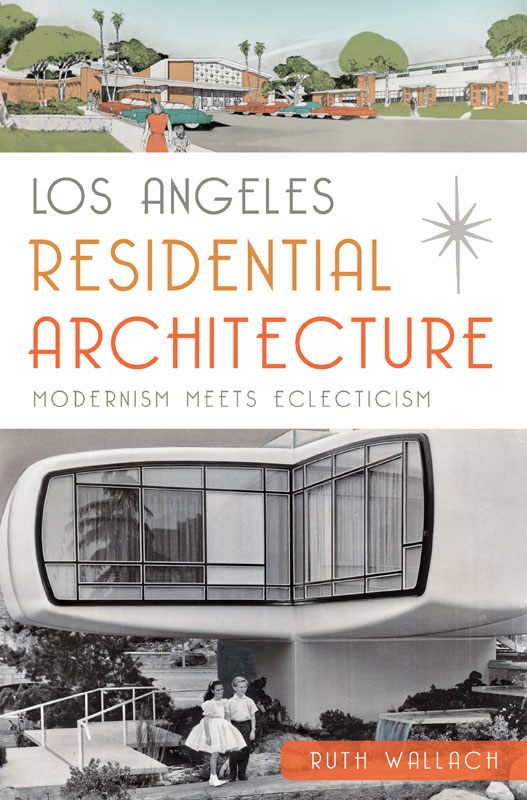

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Ruth Wallach

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.334.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015944403

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.803.6

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No researcher can make it on her own without the kind assistance of librarians and archivists. I would like to thank Giao Baker, Dace Taube and Michaela Ullmann of the USC Libraries for their cheerful assistance and Yuriy Scherbina, also of the USC Libraries, for his readiness to discuss the content of old photographs of the Los Angeles area. Special thanks go to my family for all of their encouragement and patience.

Approximately half the photographs used in this book come from three historic collections made available courtesy of the University of Southern California on behalf of the USC Libraries Special Collections. The Dick Whittington collection was created by a commercial photographer whose studio was one of the eminent photography establishments in Southern California from the mid-1920s through the 1970s. The Los Angeles Examiner photograph morgue is a collection of images that illustrate articles in the newspaper from the 1930s through the 1950s. C.C. Pierce, a commercial photographer who documented the growth of Southern California from the late nineteenth century through the 1930s, created the California Historical Society (CHS/TICOR) photographic collection.

Images of the Channel Heights housing project come from slides taken by Fritz Block, a German architect and photographer who lived in Southern California from 1938 until his death in 1955. The Block slide collection is located in the Helen Topping Architecture and Fine Arts Library at USC. Contemporary photographs come from my own personal collection.

INTRODUCTION

Starting at the turn of the twentieth century, the city of Los Angeles quickly grew as an urban center, particularly so in the 1930s and exponentially after World War II. Carey McWilliams, one of Southern Californias most astute reporters, wrote in 1946 that Los Angeless sprawling and centrifugal form was a product of several forces. One such force consisted of large waves of populations from the American Midwest that came to Southern California in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and settled into towns and settlements springing up faster than anyone could account for them. Other factors observed by McWilliams were the proliferation of automobile transportation and real estate cycles that favored horizontal urban development, or what he called a village pattern in a metropolitan environment.

In this built landscape, planned low- and mid-rise apartment houses competed for real estate with single-family home tracts, garden citystyle multifamily developments displaced the rectilinear urban grid of commercial boulevards and Modernist architectural design competed with, and was often assimilated into, historic revival styles. The mixture of contemporary and historic architectural styles was a distinctive feature of the citys urban fabric, noted by locals and by many visitors. In his 1939 satirical novel about the meaning of life, published in the United States as After Many a Summer Dies the Swan and set in Los Angeles, Aldous Huxley wrote a succinct passage that described the architectural experience of an Englishman newly arrived in Los Angeles. In this passage, the protagonist, driven through the city, observes the faades of houses in a well-heeled neighborhood as elegant and witty pastiches of Lutyens manor houses, of Little Trianons, of Monticellos; lighthearted parodies of Le Corbusiers solemn machinesfor-living-in; fantastic adaptations of Mexican haciendas and New England farms. Driving farther, he notes, [T]he houses succeeded one another, like the pavilions at some endless international exhibition. Gloucestershire followed Andalusia and gave place in turn to Touraine and Oaxaca, Dusseldorf and Massachusetts.

This book looks at the wide dissemination of architectural visual language through a variety of experiences accessible to members of the public, focusing in particular on architectural exhibitions and demonstration homes. Housing and architectural exhibitions were a common occurrence in Los Angeles throughout much of the twentieth century. Some of them were on location with actual homes built in their entirety in specific, widely publicized places. Sometimes they were open to the public for free, as were the Los Angeles Times Prize homes; in other cases, there was a small admission fee. Admission fees were generally charged to defray some of the costs associated with building and displaying demonstration homes. Occasionally, they also went to charitable purposes. For example, the proceeds from the display of the Home of Imagination, designed by architect Richard Dorman and exhibited in Leimert Park in 1953, went to benefit a foundation that aided underprivileged asthmatic children. The Home of Imagination showcased the use of various contemporary building materials, such as stone, wood and glass, and demonstrated the application of technology through such means as a power-controlled sliding door that served as the main entryway. In line with architectural thinking of the day, its design promoted the permeability of exterior and interior spaces while also emphasizing privacy, all thanks to the spatial organization of the exterior.

Exhibition homes built in situ were often raffled or sold after the conclusion of the exhibition, and sometimes they were moved to other locations, as was the case with the homes at the California House and Garden Exhibition, which took place on a plot adjacent to Wilshire Boulevard in Miracle Mile in the mid-1930s. In addition to advocating the ideals of homeownership, housing and architectural exhibitions also served an educational purpose, such as promoting principles of good, practical and artistic design to the public at large. They also purported to introduce innovative features in architecture and interior dcor, in construction methods and materials and in the design of appliances. Housing exhibitions and demonstration homes were often located in newly built subdivisions to attract clientele interested in the economic potentials of owning real estate, as well as members of the public who took away ideas about the best ways to decorate a home.

The Home of Imagination was a demonstration house designed in 1953 by Richard Dorman and built by S.J. Tamkin. Proceeds from its exhibition went to benefit underprivileged asthmatic children. Los Angeles Examiner.

In addition to architectural exhibitions on location, there were many others that were held in auditoria, often on an annual basis. These were typically large venues that allowed designers, architects and furniture stores to show the newest of their wares and to introduce new architectural and interior design ideas through temporary construction and displays, in a manner similar to museum exhibitions. Such shows were open to the public, usually for a fee, and ran for several weeks. They, too, served an educational function. Local Hollywood talent, particularly female, was often recruited to both attract audiences and regale them with explanations of particular display and design ideas. When open floor plans came into vogue after World War II, architectural exhibitions showcased how to visually separate spaces used for different daily household activities. For example, a display at a 1954 show replaced the formal dining room with an alcove that could be used for family meals. It was created by raising the floor level and was further spatially demarcated from the living room through the placement of plants. Decorative wall tiles added a feeling of orderly elegance. The dining alcove was located within easy access to the kitchen, thus also serving as a buffer between food preparation and the leisurely activities that took place in the living room next to it.

Next page