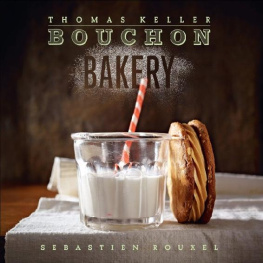

BOUCHON

THOMAS KELLER WITH JEFFREY CERCIELLO

along with Susie Heller and Michael Ruhlman

Photographs by Deborah Jones

FOR LAURA

T.K.

FOR MY PARENTS

J.C.

IN MEMORY OF CLIFF MORGAN

Cliff Morgan was a talented designer and great friend, a member of our extended family, whose influential designs are ubiquitous throughout the French Laundry, Bouchon, and Per Se.

He died unexpectedly at the age of forty-one as we were producing this book.

The entire team misses him more than we can say.

Iused to joke that I opened Bouchon, styled after the bistros of Paris, so that Id have a place to eat after cooking all night at the French Laundry. The truth of it is that bistro cooking is my favorite food to eat. Roast chicken and a salad of fresh lettuces with a simple vinaigrette. Frise salad with crisp, chewy lardons and a poached egg. A dense steak with lemon-herb butter and frites. Ask chefs what their notion of a perfect meal is and nine out of ten will name dishes such as these. These preparations, almost universally appealing, represent whats true and durable in the expanding field of the culinary arts, and are forever satisfying to eat.

I love foie gras. One of my most favorite things to eat is white truffle. To poach a lobster tail in butter or to place a crisp-skinned rouget against the vivid green of a parsley coulis is galvanizing to me as a craftsman and cook. But in the daily routine of my life, I enjoy a perfectly cooked quiche with bacon and leeks every bit as much. I am thrilled when an onion soup, with the perfect proportions of broth to onions to crouton to cheese thats molten beneath a golden crust, is set before me. The sight and aroma of a perfectly roasted chicken never fail to excite me.

Why is it that we are drawn to bistro food throughout our lives? What qualities make it excellent rather than good? What are the critical techniques in the kitchen that elevate these seemingly ordinary dishes? Why do we keep coming back to that bowl of mussels steamed with wine, garlic, and thyme, or to that lemon tart? And more, what is their impact over time as we eat them again and again? In sum, why is bistro cooking one of the most important kinds of cooking, and whats the source of its power? These are the questions I sought to understand when I opened Bouchon, and the ones we explore in this book.

Whereas The French Laundry Cookbook is about using the ideas and techniques of classic cuisine as a springboard for the imagination to create new dishes, Bouchon is about maintaining classic traditions, renewing our respect for those great dishes, holding them up to the light to understand them, in order to perfect them. To that end, the recipes detail the important qualities to strive for in each dishwhether its the ratio of ingredients in onion soup, the size you cut your lardons for a beef bourguignon, the texture of a crme carameland the techniques youll need to achieve them.

The recipes in this book fall into a category of food served at what we think of as a bistro, a type of restaurant with origins in nineteenth-century Paris that has become all but universal. Yet in a way, the bistro and its food have become victims of success. The word bistro is used so pervasively in so many different ways that its in danger of losing its meaning altogether. Indeed, I use the name Bouchon, which is a similar type of restaurant that continues to flourish in Lyon, France, because in America, bistro doesnt really mean anything more specific than casual.

Bistro dishes have become somewhat debased as well by overuse and lack of understanding. The quiche, for instance, never had a chance in America because we were told to make a quiche in a pie shell. You cant make a proper quiche in a pie shell; it needs a deep tart crust. Bistro food is not about specialized ingredients, rather it is about precision of technique brought to bear on ordinary ingredients. Its easy to make foie gras and truffles taste good. But how do you combine lettuce, salt, vinegar, and oil in a way that is elegant and exquisite? Indeed, the very fact that these dishes have fewer main ingredients, typically common inexpensive ingredientschicken and salt, lets sayonly raises the bar.

And this in a way renders moot the question why write a bouchon cookbook now, rather than further exploring cutting-edge haute cuisine. I dont distinguish between the two in terms of quality. The success of any kind of cooking is determined by technique, and its ultimate quality is determined by the standards you bring to the execution of that technique. The standards for bistro cooking are no different from the standards of the French Laundry, though the ingredients and presentation are different.

My love of this food didnt begin in France, where I spent a year in starred kitchens, or, for that matter, in Manhattan, where I ate at my first bistro. I really connected with this kind of cooking at a place called La Rive outside Catskill, New York, in the Hudson Valley, where I worked for several years in my early twenties before I ever set foot in France. There Ren Macary, who owned it with his wife, Paulette, served traditional French comfort food in a country setting.

All kinds of hors doeuvres were set out across a vast table in the dining roombeets, radishes with butter, cleri rmoulade, lentil salad, cornichons, pts, and bread, ready to be brought straight to the table. On the piano, all the dessertsthe custards and chocolate mousse and tartswere also on view, waiting to be served. This was my first experience not so much with French cooking but rather with the ethics and aesthetics of the French way with food. One of my great memories is of watching Ren make a salad. He would salt it, then put on the oil, to coat the lettuce and protect it from the acid, and then he would add the acid. He would never combine the two then pour them on; vinegar was the seasoning element. What made watching him exciting was the anticipated joy of eating that salad, the richness of the oil, the sparks of vinegar that would come through.

Id been taught the basics of this kind of cookery at a big club in Rhode Island under a Frenchman named Roland Henin. There I learned how to turn inexpensive cuts into elegant stews and how to properly cook vegetables. But my three years in upstate New York marked a time when I was learning on my own and cooking by myself, in what was really a kind of idyll in my career. I learned how to let time and cooking work their natural manipulations, to let the food be what it is. I was very happy there and I associate this food with happy times.

And that, ultimately, is what makes us cherish and revere French comfort foodour emotional connection to it, the feeling we get when we see a perfectly roasted chicken or a beautiful steak and a pile of frites or a dozen perfect oysters waiting to be shared. This kind of food makes us feel good just looking at it. This food makes people happy.

MY FAVORITE SIMPLE ROAST CHICKEN MON POULET RTI