About the Author

R ade B. Vukmir, MD, JD is president of Critical Care Medicine Associates, a medical service and consulting enterprise founded in 1991. He is trained in emergency medicine and critical care medicine, and has a legal degree with a specialization in health law.

This company has been successful over the last eighteen years providing a wide variety of clinical medical activity, education, medicolegal services, and business consultation services.

Dr. Vukmir has authored over forty journal articles. Previous books published include Care of the Critically Ill (Parthenon Press) and AirwayManagement in the Critically Ill (Parthenon Press) in the medical genre.

Dr. Vukmirs third publication is a historical non-fiction novel entitled The Mill (University Press of America) This latter work addresses the changing business environment of an aging steel industry and its impact on the day-to-day lives of the inhabitants of its once thriving industrial town. Lessons Learned: Successful Management in a Changing Marketplace (University Press of America) attempts to unite a wide variety of work experience and business principals.

His most recent books, The ER: A Year in the Life (Hamilton Books) and ER: One Good Thing a Day (Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group) attempt to relate to the reader both the joys and sadness encountered taking care of patients, families, and each other in the emergency department.

Chapter 1

Introduction

E very emergency department (ED) strives to attain an optimal level of effectiveness, while trying to achieve its valid patient care mission. There are numerous factors that affect the departmental operation. The most prominent issues obviously include the patient number, acuity and rapidity of presentation, balanced by staff and bed availabilityboth in the EDas well as hospital admission bed vacancy.

An important consideration is that these factors are intimately intertwined so that a delay in one portion of the care chain involves other aspects of care as well.

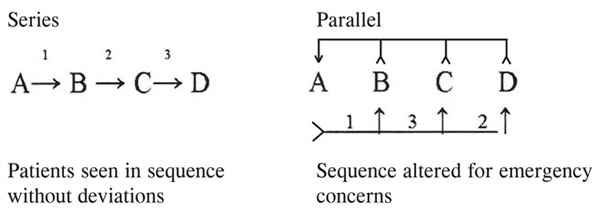

The key to emergency medicine is parallel process thinking rather than series patient management (Figure 1). This concept is analogous to the physics of electrical circuitry allowing an alternative pathway for delivery if an impedance to flow is encountered. This attribute allows multiple tasks to be addressed simultaneously rather than sequentially.

Figure 1. Patient Management

Empowering each member of the staff to contribute and offer insight to the process will pay long term dividends to the institution. The Team Approach for all health care providers encourages tangible participation and buy in to the process. The quickest way to disenfranchise the group is to offer oversight and protocols without their input into the patient care process they perform involved in this care.

The best-run emergency departments, therefore, provide a proper balance of effectiveness of patient care accompanied by the maximization of the efficiency of the health care delivery system providing that care.

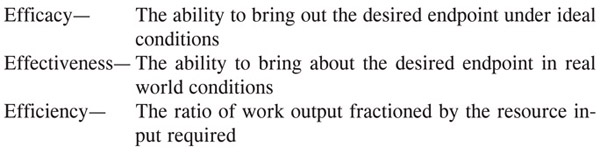

The consultation industry has a tendency to focus on efficacy with a theoretic constructive of work output that is untestedan abstract goal, if you will. This concept is in contrast to effectiveness or the actual work product in real life working conditions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Work Productivity Measures

Therefore, the reference point for effectiveness must be contemporaneous actual clinical experience. Occasional observations of work interactions that are in the distant past are not productive or accurate.

Lastly, the concept of efficiency balancing the work product with the resources consumed is the most critical analysis point for the discussion.

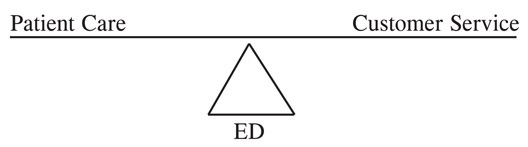

This philosophy is tempered by the incorporation of a service excellence customer service model addressing the two areas of most concern: the timing of the visit and the amount of caring exhibited by the staff.1

This approach culminates in the maximally efficient emergency department, providing both optimal patient care and customer-focused efficient care delivery (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Optimal Balance

References

1. Vukmir, R.B. Customer satisfaction. International Journal of HealthCare Quality Assurance Incorporating Leadership in Health Services 2006; 19(1): 8 31.

Chapter 10

Ancillary Care Providers

Paramedics, Technicians, Unit

Secretaries

T he optimum approach is the shared responsibility and accountability of every employee, who have the power to make the daily operations succeed or fail. Empowered and motivated employees who feel their opinions and contributions matter are the core of this program.

Cross-training programs for health care professionals have proliferated, but they have been associated with mixed results. The two most common formats are the unit secretary patient care technician and the housekeeping patient care management hybrid job roles.

The major issue appears to be deficits in individual, specific accountability. Interestingly, programs that have returned to individual job assignments have prospered, improving both staff morale and customer service. These positions stress individual areas of responsibility improved by specific self-governance programs.

An effective use of the Team Approach model is the staff progression model of development. This requires at first a division of labor that identifies particular contributions to the work product by the unit secretary, technician, paramedic, LPN, RN, and RN specialist.

The use of ED technicians has been well-described with the group featuring military medic or EMT paramedic training. Their skill set involves procedural assistance with lacerations, wound care, abscess drainage, orthopedic splinting, IV placement, and blood draws for laboratory assessment. They do not, however, administer medicine, interpret tests, answer EMS radio calls or function without physician supervision in most areas. The experience at the University of New Mexico found only 3 complaints with 450,000 visits over a 15-year period.1

Paramedics have also been utilized in the ED since the early 80s in about 20% of facilities nationally. The services they offered included general assistance (94%), patient transport (89%), IV access (78%), laboratory specimen transport (67%), medication administration (22%), laceration repair (11%), narcotic administration (11%), and endotracheal intubation (6%).2

Advantages of including a paramedic in the ED staffing model include improvement in the ED EMS interface (100%), cost effectiveness (89%), and introduction of the prehospital perspective to the ED; while disadvantages include the introduction of intra-staff conflict (28%) and inadequate training (11%).

Overall, there was an economic benefit suggested with an hourly pay rate of 67% compared to that offered to the RN nursing staff. There was, however, an equal split in response to this staffing resource with the clinical aggressiveness of the group viewed as both a potential advantage and disadvantage, at least in a pediatric emergency medicine setting.

An effective use of the Team Approach model is the internal staff progression model of development. This requires at first a division of labor that identifies particular contributions to the effort, whether unit secretary, technician, paramedic, LPN, RN, or RN specialist.