The extraordinariness of simple food

(La straordinariet del cibo semplice)

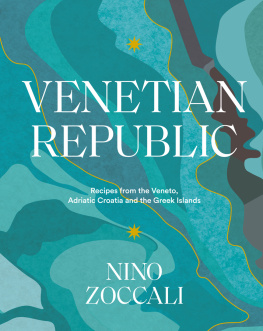

Q uite a few years ago, when I was considerably younger than I am today, I opened my first restaurant in the Margaret River wine region in Western Australia with Russell Barr, an old childhood friend. We had both grown up in the small coastal city of Bunbury, close to this wonderful place. We loved the region; it was a renowned surfing coastline and we were both very eager surfers in those days. As restaurateurs, however, we were very inexperienced and had a lot to learn. But what we lacked in experience we definitely made up for in passion and enthusiasm. Russell looked after the front of house and I looked after the kitchen.

One day, not long after the opening of the restaurant, I received a phone call from my father advising me that he was coming to the restaurant with a group of people and that he would bring a good friend of his, a certain Swiss man by the name of Max Fehr. Max was a highly awarded chef and had successfully owned and operated restaurants for many years. His illustrious cooking career had also included opening restaurants and hotels all over the world and at the time he was still an international Olympic culinary judge. As you can imagine, I was young (25 years old), relatively inexperienced and extremely nervous about cooking for him.

As the date of my fathers trip drew closer, I became almost paralysed with fear at the thought of what Max might order. Would it be the veal? After all, he was Swiss and the Swiss loved veal. Would it be the beef? The North West cod? The Fremantle sardines? The pork cutlets? Then I thought, Surely he is not going to order pasta, which is such a simple and relatively uninteresting option for someone like him.

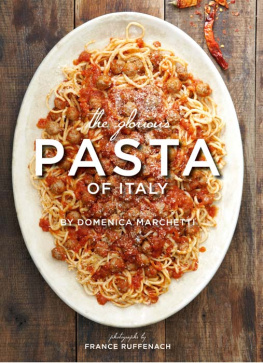

The evening of the dinner finally arrived, and when the order reached the kitchen, I was, to say the least, left in a state of shock. Max ordered, quite simply, a plate of fettuccine with neapolitan tomato sauce with basil, chilli and garlic. He couldnt have ordered a more basic dish and I have to say I felt slightly insulted.

Max ate the dish and then sent magnanimous compliments back to the kitchen. He told me that the pasta was as wonderful as Italian food could be and that I should be very proud of successfully carrying on such a magnificent tradition. He was also very interested to know how I made the sauce, how much olive oil Id used, whether I used onions, the ratio of the ingredients and so on. I appreciated Maxs compliments but thought, Thats not what restaurant food should look or taste like.

At the end of the evening service, when most of the patrons had left the restaurant, I decided to cook myself the same dish. And with just one small mouthful I was reminded of the thousands of times I had eaten this and many other simple pasta dishes, simple food that delivers such extreme satisfaction because it is cooked with love, care, passion and often obsession. I thought to myself, A simple lesson in the extraordinariness of simple food.' If it is done very wellwith the right flavour and texture, the sauce made from the ripest tomatoes, the pasta cooked perfectly al dentea simple plate of pasta alla napoletana (and lets face it, it doesnt get simpler than that) can, and indeed should be, a truly delightful experience.

On this particular evening I learnt a very important lesson, one that has defined my cooking philosophy and stayed with me for my entire careerthat the quintessential cornerstone of great Italian cooking is simplicity, quality and, above all else, flavour.

Since that evening, I have cooked this simple dish, or close versions, for a multitude of people: heads of state, prime ministers, respected business leaders, Formula One racing car drivers, famous musicians, actors, artists, sports stars and so on. According to Arrigo Cipriani, of Venices iconic Harrys Bar, Spaghetti al pomodoro is one of those basic recipes that every Italian restaurant should be able to do well. In fact, you can use the dish to judge a restaurant. I couldnt agree more.

Indeed, simple can be stunning if it is done well. It is no accident that spaghetti bolognaisethe anglicised version of spaghetti con raghas colonised much of the culinary Western landscape. While the pasta bolognaise you find outside of Italy may vary significantly from what you get in Bologna, it is remarkable that this dish is the most popularly eaten meal in Australia. And six out of every ten adults in the UK claim to be able to make a bolognaise sauce without a recipe!

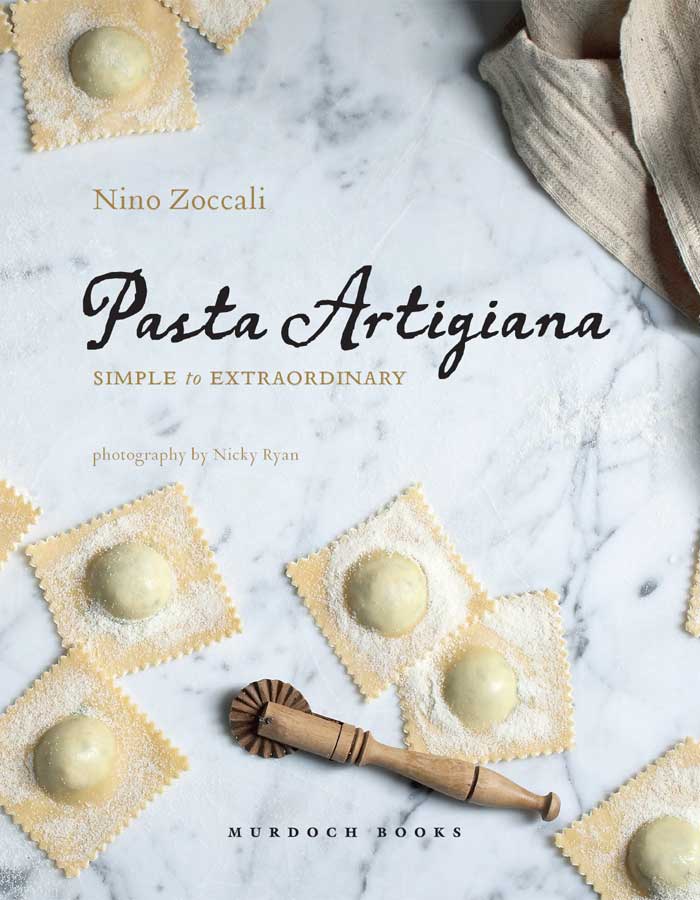

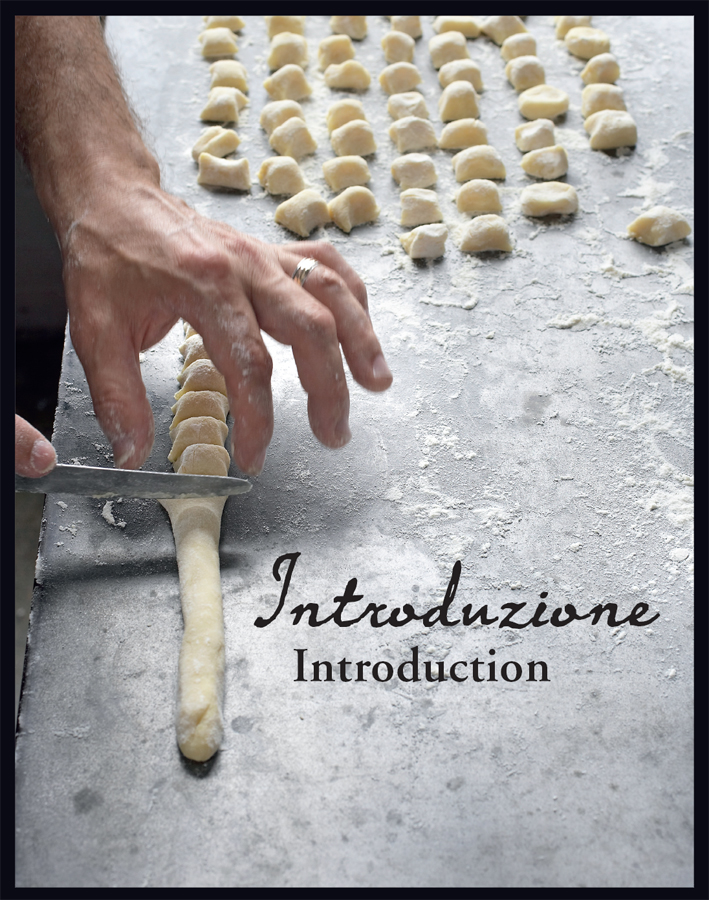

But dont be fooled. In Italian cooking, simple doesnt really mean simple. It can mean quick, but it only means simple once you know what you are doing. And it nearly always means regional. In the Bologna region alone there are hundreds of recorded variations of the bolognaise rag. Many years have gone into perfecting regional pasta dishes where traditions are strong and meaningful. Growing up in my family, it took at least three people to test whether the pasta was al dente before serving it. Similarly, I believe I could write a novella just on the ripeness and variety of tomatoes used for tomato sauce. With Italian food, like any great provincial food, simple things are not simple if you want to do them well, and pasta is a very good case in point, which is why practice and learning correct techniques will see markedly better results.

It is believed that the tradition of making and eating pasta is over 7000 years old. It was either the Ancient Greeks or the Etruscans who first worked out how to make pasta, just before the Arabs discovered the significant benefits it brought as a transportable food. But if the Italians didnt invent pasta, they have certainly turned it into a fine art over a long period of time. And they have developed a fine art out of virtually nothing. Growing up, my mother would often say to me, The thing about Italian cooking is that it creates amazing things out of very little.

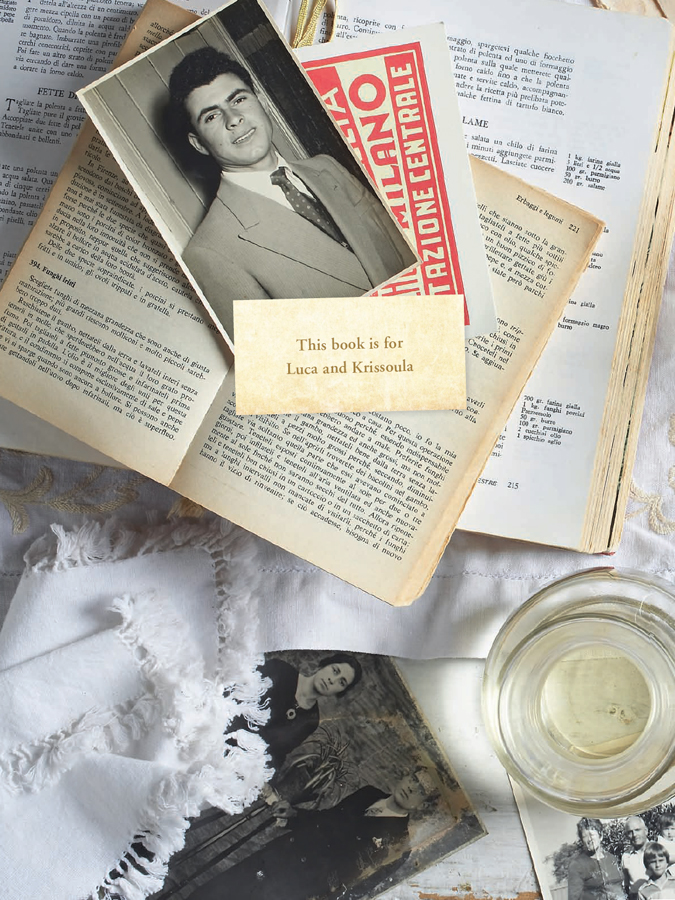

I have witnessed this through my whole life, first from my father, aunties and uncles wholike generations of other Italian emigrantsleft their beloved land to create better lives for themselves and their children. And it is ironic that while they left behind a life of abject poverty, they took with them culinary magic, the alchemy of flavour.

The truth in my mothers statement is really a window into understanding how pasta, like most Italian cuisine, has evolved out of poverty or la cucina povera, and how it ties together an obsession with flavour that spans the whole of Italy, no matter what the region. There is nothing more ubiquitous in Italian food, in any corner of the country, than flavoursome pasta dishes. Nothing more economical can support the range of nutrient-rich ingredients that come from the different microclimates that span this great peninsula and its islands. Quite simply, there is nothing more Italian than pasta.

This ability to create amazing things out of very little is evidenced all over Italy, whether it is in the plethora of tomato and olive oil-based dishes of the south, the wonderful egg pasta dishes of central and northern Italy, border-region dishes such as