OPEN INNOVATION

New Product Development Essentials from the PDMA

Edited by

Charles H. Noble

Serdar S. Durmusoglu

Abbie Griffin

Cover Design: C. Wallace

Cover Illustration: Vector Swirl iStock.com/antishock

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Copyright 2014 Product Development and Management Association. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with the respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

ISBN 978-1-118-77077-1 (cloth); ISBN 978-1-118-77078-8 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118-77085-6 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118-94716-6 (ebk)

To three amazing ladies who've made me who I am: Stephanie,

Dolores, and JennyCN

To Tansu, my little angelSD

To Ken for supporting me in all my research and publication

endeavors for over a decadeAG

INTRODUCTION

THE JOURNEY INTO OPEN INNOVATION

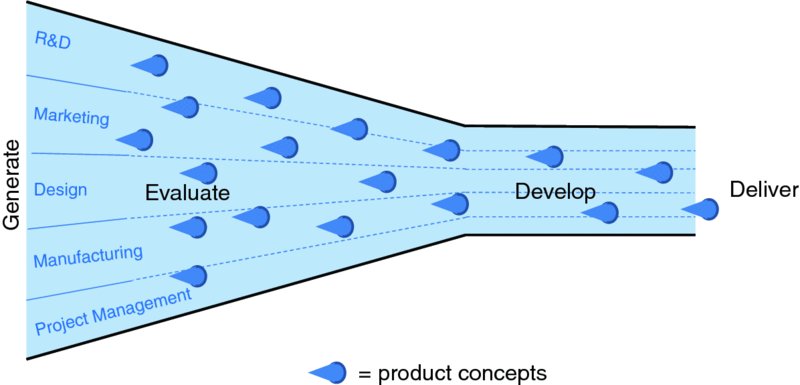

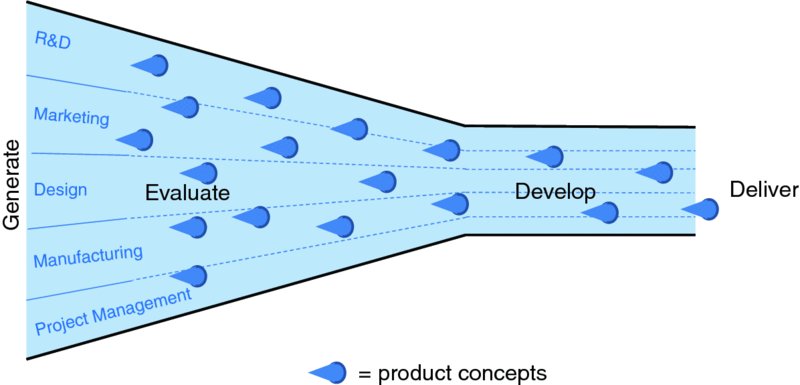

The idea of cultivating firm innovation has long been associated with secrecy, fear of competition, and a general distrust of any entity outside the corporate walls. In this view (shown in ), product concepts are developed across various organizational functions, but it is a hard-walled process in which input from outside the firm is not sought or valued, and concepts are jealously guarded from leaks to the outside world.

: A Typical Closed Approach to Innovation

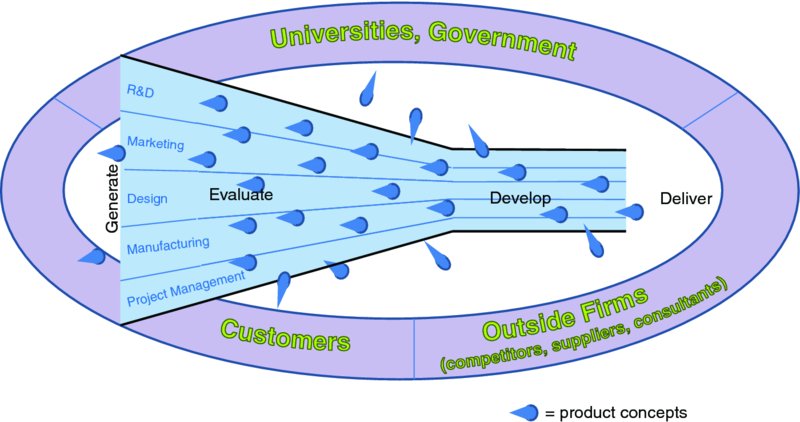

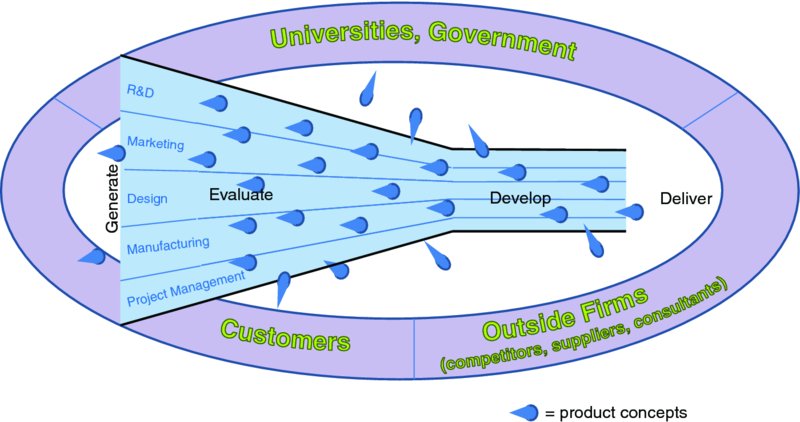

The term Open Innovation is generally credited to Henry Chesbrough from his 2005 book and prior writings illustrates this general concept. More than ever, the benefits of Open Innovation (OI) are being explored and under its umbrella can be found increasingly popular techniques such as consumer co-creation, crowdsourcing, idea competitions, collaborative design, and other approaches.

: A General View of Open Innovation

Despite the recent focus on this approach, elements of OI have in fact been in existence for centuries. Consider the following:

- In 1714, the British government, through an Act of Parliament, offered the Longitude Prize to anyone who could develop a practical method for the precise determination of a ship's longitude. The winner was John Harrison, who received 14,315 for his work on chronometers.

- In 1795, Napoleon offered a 12,000-franc prize to drive innovation in food preservation, spurring a French brewer and confectioner named Nicholas Appert to develop an effective canning process to avoid spoilage.

- In 1919, New York City hotel owner Raymond Orteig offered a $25,000 reward to the first allied aviator(s) to fly nonstop from New York City to Paris or vice versa. It was a relatively unknown individual, Charles Lindbergh, who won the prize in 1927 in his aircraft, Spirit of St. Louis, and made history.

- In recent years, the X PRIZE Foundation sponsored a space competition and offered a $10,000,000 prize for the first nongovernment organization to launch a reusable manned spacecraft into space twice within two weeks.

- Eli Lilly pioneered the modern idea of crowdsourcing in 2001 when they began to post research questions openly (online) to scientists and other outsiders to augment their own R&D efforts. From this effort, they developed and spun off a new company, InnoCentive, to offer crowdsourcing to other companies.

- The use of beta invitations has been practiced for decades in the video game industry. In this model, which could be considered a form of OI crowdsourcing, a software developer releases a beta (or early, likely flawed) version to users for testing and commentary. This results in many expert hours of development being applied in a short time, thereby improving the product quickly and cost-effectively.

While these principles have been sporadically tried in the past, the recent move to focus thinking around the term Open Innovation has increased attention and has helped explore the full breadth of the concept with its many dimensions and implications.

Despite the hoopla and the calls for many goods and service firms to pursue this approach, there are certainly hurdles and cautions to consider. The loss of control is a fundamental worry, manifesting itself in many waysin that competitors can have more insight into your early stage product pipeline and in that the same core ideas may be shared with others. There is also a valid concern that allowing users to enter into your innovation process creates an expectation with them that their ideas will be valued and implemented, which may not always be the case, resulting in disappointment. Last is the potentially more daunting worry that great ideas can't come from a crowd, which inherently produce compromise and mediocrity.

Idea sifting also can be an overwhelming challenge for firms pursuing this approach with gusto. For example, the community-driven innovation site Quirky has, as of this writing, almost 700,000 individuals who have contributed somehow to various product innovation processesthrough raw ideas, branding suggestions, design insights, and so on. All of that enormous energy has culminated in only just over 400 products reaching the marketplace to this point. The vast majority of ideas and refinements are rejected, either by the community or, in a more organizationally taxing way, by the firm's own marketing, design, and manufacturing experts. This illustrates the skill shift seemingly required in firms pursuing Open Innovationfrom technical expertise in personal product development to screening and sifting through potentially thousands of inputs for a few with radical potential. Therefore, it seems fairly clear that cost savings should not be the main driver for the firm embarking down the path to Open Innovation.

Next page