18 JUNE 2020

At the time of writing, we are in the middle of a global pandemic that has caused the entire world to shut down. With restaurants closed, we have had to reacquaint ourselves with home cooking. For some, this has presented itself primarily as a chore or an annoyance especially the washing up. But for me, this has been an almost unconditional joy. I have relished the simplicity of home cooking and the freedom of it: the permission to cook creatively and earnestly without having to worry about paying customers. I have cooked things I have always loved cooking, and I have cooked things I love eating but never have had the time to cook, and I have cooked things I have never cooked before.

Since we cannot travel, I have also turned to cooking as a form of escapism. Of course you cant actually, physically, transport yourself to a night market in Chiang Mai when you eat khao soi, any more than Proust could reverse the ageing process or travel through time when he ate a madeleine. But you can get somewhere, mentally, through food, and the journey can be profound. I made carnitas tacos that put me, for a moment, in a squarely Los Angeles state of mind. I barbecued rabbit and drank Kinnie to take me back to Malta, a year after we went on holiday there. I made a proper deep-dish Chicago-style pizza on the day we were supposed to fly back to the Midwest. And I made garlicky prawn wontons, slicked with chilli oil, to bring me to my favourite Sichuanese restaurants, peppered throughout Londons Docklands: a region now so inaccessible, it may as well have been in China itself.

Of course, it doesnt always work. You cant really recreate the effect of eating certain things in the setting where theyre meant to be eaten, and my post-lockdown to-do list contains exactly these types of context-dependent food experience: the chopsticks-on-ceramic clamour of a busy dim sum dining room; the plutocratic, red wine-and-bearnaise-sodden excess of a steakhouse; the carnival of smoke, sugar, soju and spice that is a Korean barbecue joint. There are some things that you cant quite do justice to at home.

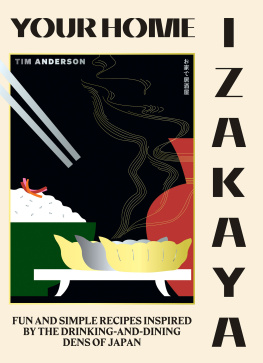

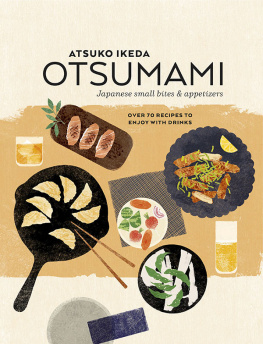

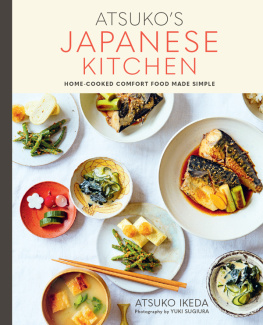

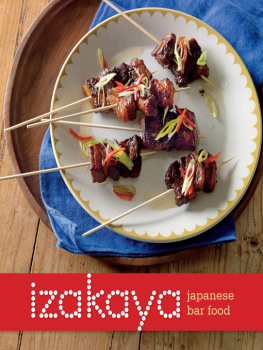

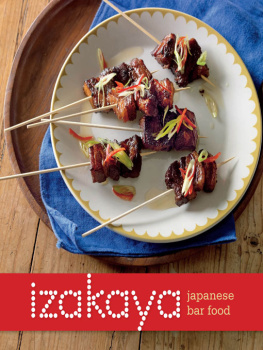

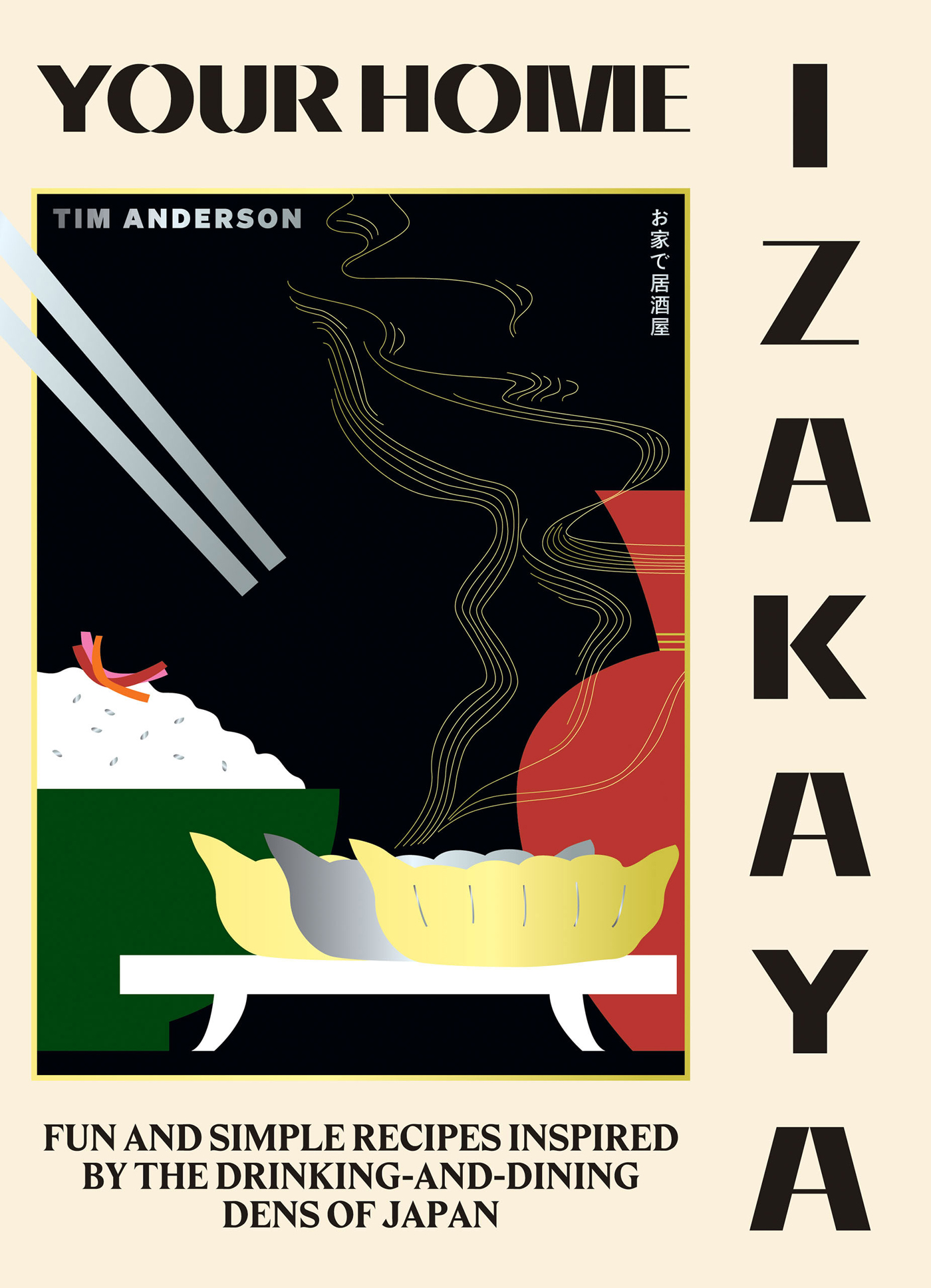

This included, I thought, my very favourite type of place to eat: izakaya. Id always figured that izakaya are too dependent on their intangible characteristics to successfully recreate at home. Theyre about the service, the atmosphere and, crucially, the ability to have an effortless time because somebody else is putting in the effort. You do not have to worry about dirty dishes in an izakaya. Thats not part of the deal. There are no toddlers to look after in an izakaya. There are no worries at all: the izakaya is a stress-free zone. How can you achieve this without physically relocating to that third space separate from your workplace and your home? Indeed, how can you achieve this without actually going to Japan? It seemed impossible.

But then I remembered Bar Yuki.

In preparing to write this book, I began reminiscing about the best izakaya experiences Ive ever had. There have been so many, but to be honest, my specific memories of most of them are quite hazy, blurred by alcohol and age-related brain degeneration. But one izakaya did stand out in my mind as an all-time favourite: Bar Yuki. I was trying to think of really good izakaya here in London and, unfortunately, there are not very many at all. This isnt the fault of chefs or restaurateurs in particular; its just that izakaya work better in Japan, for all kinds of reasons. But I was still startled by the realisation that my favourite izakaya in London isnt an actual restaurant. Its my friend Yukis flat, in Limehouse.

What makes Bar Yuki, as she calls it, so good? Well, first of all, Yuki is a very good cook. Very, annoyingly good. When I think of chefs I look up to, shes always at the top of the list. Yuki was born and raised in the south of Japan, and she has been cooking her entire life; by the age of five, she was already helping her mother with odd jobs in the kitchen, including, most impressively, gutting fish. Yuki credits her mother and grandparents for teaching her how to cook, and not just basic Japanese home cooking. Apparently, if Yuki said she liked something at a restaurant while she was out with her family, her mother would try to figure out what was in it and then recreate it at home. This is something Yuki now does as well, and because shes a studious, serious cook, pretty much everything she turns her hand to is enviably delicious.

But its not just her food that impresses; its also her generosity. Even when I pop in unexpectedly, Yuki will lay out a platter of charcuterie or fry up some gyoza from the freezer. Perhaps too much is made of omotenashi, Japans culture of superlative hospitality, but it is one of those clichs that does tend to be true more often than not.

I asked Yuki if her family also instilled in her a sense of obligation to serve house guests, and she explained that its a bit more complicated than that. First of all, there is a cultural expectation in Japan that you should offer something to people in your home, but also a reciprocal expectation that theyll bring something for you. This give-and-take is so ingrained in Japanese society that it simply feels natural to provide a little something for visitors. As for omotenashi, Yuki explains that in friends homes or in izakaya, its the same spirit of hospitality youd find in more formal settings but expressed in a friendlier, more laid-back way. Izakaya are like pubs, she says, contrasting them with high-end cocktail bars; the experience and the service are basically the same, but the communication with the person behind the bar is different.

Additionally, Yuki says it just seems wrong to see people drinking without food like theres something missing. She confesses to being a lightweight who cant really drink without eating, so sometimes she makes food simply as a means of self-preservation, and I get to reap the benefits. I tend to make something because I want to have it! she says with a laugh. But she also says that the impulse to serve food when people are drinking is automatic, because thats what shes always known its the norm in Japan. When she said this, it did occur to me that I could hardly think of any situations in Japan where people were drinking and not eating something along with it; even at really casual bars that didnt serve food, youd at least be given a little bowl of nuts or rice crackers, free of charge. Convenience stores even sell cans of beer with little packets of snacks attached directly to them. Spend enough time in Japan and youll develop a sense that drinking just doesnt feel right without something to nibble on. I think drinking with snacks is just in our genes, in our blood, Yuki explains. She says that making a good home izakaya may actually be as simple as having small bits you can always serve on hand, like ham, pickles or cheese just a little something to make your guests, or yourself, feel more nourished and provided for.

Next page