Table of Contents

Dedicated

to

Indias diplomatic fraternity

Contents

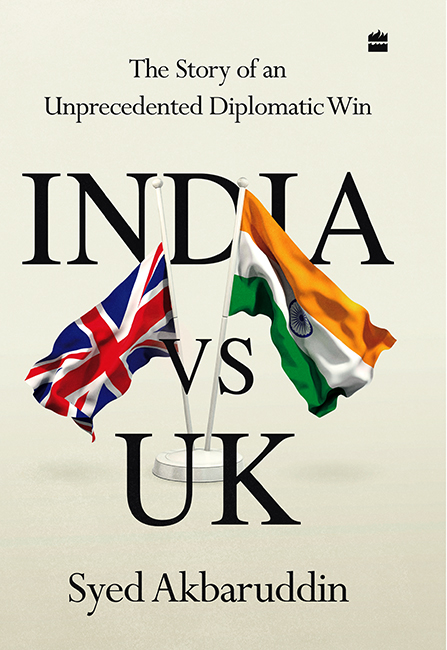

I N SITUATIONS OF global flux, changes happen. Shifts occur although they are not always planned and plotted for. At times, fault lines long in the making come to the fore due to unforeseen circumstances. In multilateral diplomacy, such changes are rare but not unknown. They have a bearing that is little understood when they occur. Their impact tends to unveil itself only over a protracted period of time. Nevertheless, a record of events is always useful to make sense of the changes and place them in proper perspective.

Since Independence, Indias foreign policy orientation has always included a strong commitment to multilateralism. In fact, being present at the inception of the United Nations (UN) as a founding member, as it was in the League of Nations too even prior to Independence, makes for our historical uniqueness in this key multilateral forum. It is a truism that since then Indian diplomacy has excelled in several aspects of multilateral diplomacy. This has manifested in myriad ways. Setting pioneering agendas, promoting policy options beneficial for developing states, bridge-building in complex treaty negotiations, promoting the global observance of common civilizational values, the rendering of dedicated services by very many Indians in international civil service, and the stellar contributions of Indian military personnel on UN peacekeeping missions are a few of the many facets of Indias role at the UN that can be listed and buttressed with numerous examples.

Independent India, however, started off its journey on the wrong foot in one crucial aspect of multilateral diplomacywinning in major elections.

It took more than forty days and a dozen votes for the outcome to be decided. India withdrew as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic consistently out-polled it in every vote. Around midday of 13 November 1947, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was declared elected, polling thirty-five out of thirty-seven valid votes, two invalid ballots and fifteen abstentions. The required majority threshold was twenty-six votes.

This first defeat of independent India in a significant multilateral election in the UN General Assembly meant that Indias engagement with the Security Council was not about to begin as a decision-maker on peace and security, but as a plaintiff. It was on 6 January 1948 that the Security Council first considered the IndiaPakistan question, an item that remains on the agenda more than seventy years later.

Elections at the UN, almost always, are an inter-state contest. Even when they are formally intended to choose independent individuals, the state from which the individual hails is inevitably the most significant factor. The UN platform is one of inter-state contestation. States play a pivotal role in every election at the UNnot only as voters but also as the principal backers and supporters of the candidates nominated by them or by others on their behalf. Consequently, success or the lack of it in any multilateral election is primarily on account of the efforts of states, rather than individuals.

No election is as political and hotly contested as the one for independent judges of the International Court of Justice (ICJ). A year after Indias Independence, in 1948, the eminent jurist Dr B.N. Rau was a candidate to a seat of the ICJ. The complicated electoral process made the ICJ elections the most complex in the entire UN system. The election went into multiple rounds in both the bodies (General Assembly and Security Council), which voted simultaneously and independently to elect five judges. Alas, Indias nominee fell short when the final results were announced.

Since then, India has contested successfully in hundreds of UN elections. But then, as they say, there are Elections and then there are other elections. India has contested ten more elections to the Security Council since, winning eight of them. These were elections in the UN sense of the termin that they required balloting. However, many were contests without competition. Seven times, India went into the Security Council elections on a clean slate. There was no competitor from the group we were contesting. In many cases, we had the endorsement of the group. This made the ballot less of a stress test, as victory was ensured without a contest.

Only once, for the term of 1967-68, did we win a competitive election to the Security Council against Syria in one round.

Candidates from India also contested many more times for a seat at the ICJ following the loss in 1948. Yet, never had a first effort by an Indian candidate for a full term to the ICJ resulted in victory until Judge Dalveer Bhandari won a full nine-year term in a historic election in 2017.

Before this, two other candidates from India had contested and won three full nine-year terms. Both were, however, candidates who had contested earlier and lost, before they won their first full term. They won when they contested at the next election, having made their candidature plans known years in advance. Dr B.N. Rau, having lost in 1948, contested again in 1951, when he was the Indian Permanent Representative to the UN. He won in the first round of balloting.

The rest of the elections that we contested and won to the ICJ were only for the remainder of the unfinished terms of incumbents who either died or resigned. Fundamentally, these are different types of elections and similar to bye-elections.

Major elections at the UN do not usually engender excitement in the outside world. Within the UN system, they are often a useful barometer of the standing of an individual member state at a particular juncture and the mood of other UN members. They bring together all elements of a states acumen in multilateral diplomacy as well as a states ability to leverage the intensity of bilateral ties to its advantage on the global platform. They are also a useful way of understanding the ground realities that diplomats are required to navigate in fulfilling foreign policy objectives.

Against this background, Indias success in the titanic election tussle of 2017, upending all past precedents, is a good case study to understand the changing contours of Indias recent approach to global fora. How and why did India decide to contest this election? What was the decision-making process? What were the stakes involved? How did this election metamorphose into one which upturned conventions and ended with a paradigm shift never witnessed before in the history of UN elections? What were the key factors in Indias success? Who helped and what were the hindrances? What was the difference in Indias approach so that it could avoid becoming, to use a sporting term, a choker? What were the lessons learnt? What does it augur for Indias future role at the UN and beyond?

Foreign policy is about grand strategy as well as about getting the nuts and bolts of diplomacy right. This is all the more so amidst the tumult that the global order is currently confronting. While high-profile events gather attention, unpublicized shifts in working methods that take place below the formal level also are important ingredients of quiet changes. Cooperating, coordinating, agreeing and implementing mutually agreed goals with a wide and diverse array of partners may not catch attention but are as important as visualizing, designing, strategizing and planning policies with key global players. Even as, understandably, the focus is on the big-ticket items, little-noticed subterranean changes in the broader framework of continuity in Indias recent diplomatic experience are also making a difference. These changes are, as yet, an evolving narrative that has still to be told. This book is a contribution towards telling that story.