Contents

Page List

Guide

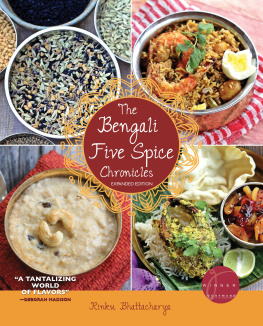

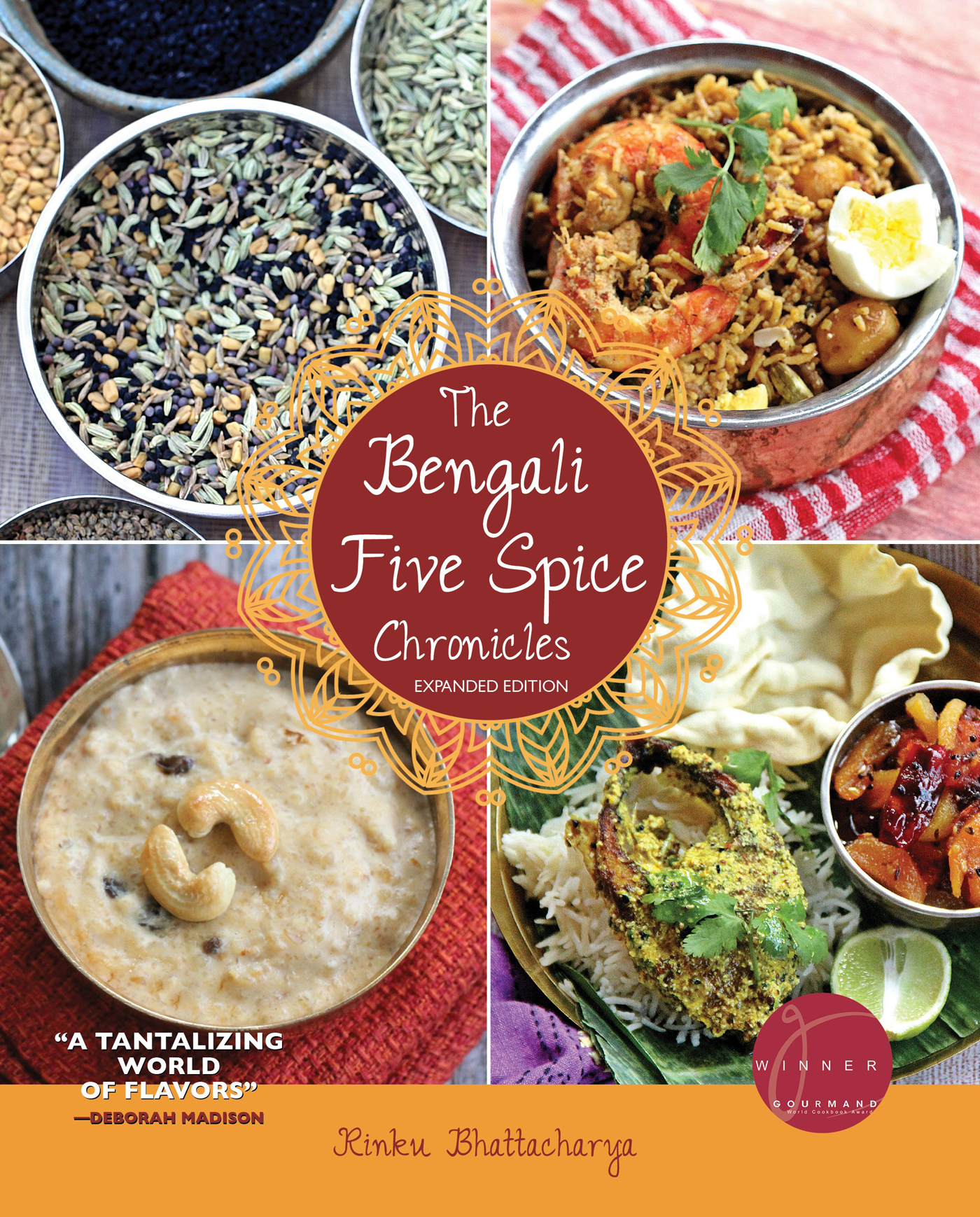

The

Bengali

Five Spice Chronicles

Expanded Edition

The

Bengali

Five Spice Chronicles

Exploring the Cuisine of Eastern India

Expanded Edition

Rinku Bhattacharya

Hippocrene Books, Inc.

New York

Expanded Edition 2021 Rinku Bhattacharya.

Copyright 2012 Rinku Bhattacharya.

All rights reserved.

For further information, contact:

HIPPOCRENE BOOKS, INC.

171 Madison Avenue

New York, NY 10016

www.hippocrenebooks.com

Original edition ISBNs: 978-0-7818-1305-1 / 0-7818-1305-0

Expanded Edition ISBN-13: 978-0-7818-1423-2

Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress

Printed in the United States of America.

Dedication

This book is dedicated to:

The past

Bapi (father) and Dida (grandmother),

who form the foundation of my life

The present

Ma and Anshul and Khokon,

who help me stay grounded in this journey of life

The future

Deepta and Aadi, my children,

who help me find beauty in nature everyday

Contents

by Stanley Elwood Brush

Foreword

by Stanley Elwood Brush

Its a pleasure to write a short introduction to a cookbook on Bengali cuisine. Particularly because it relates to the land of my birth, expatriate infant though I was, and the author is someone I have known since her graduate student days at a New England university where I taught Indian history. She is an expatriate, of sorts, too, belonging to Bengali parents employed by a transnational corporation in Africa.

I grew up in the Bengal railway colony town of Kharagpur, and my first breath was air mingled with the aromas emanating from the cook house on the back veranda of the Union Church parsonage. My milk bottles were filled with milk (boiled, of course) from local cows and water buffaloes and my favorite meal was the rice and dal lentils and chicken curry that our cook used to conjure up from a mysterious blend of ingredients that his wife ground up on a stone stained yellow from years of service for this purpose. The unpleasant part was having to witness the execution of the chicken and its unseemly de-feathering. As a boy I was unaware, of course, of the finer points of the stuff that went into curry, but I was very aware that the curry at Tamil wedding parties (there was a colony of Bengal-Napgur Railway Tamil employees who used the facilities at the Union Church compound) was pitched much higher on the jhal (hot pepper) scale than Bengali curry.

Rice and curry, dal and chapattis were clearly the favorite menu items on our boarding school menu in the hills. The flat, flexible whole wheat flour chapattis (called rotis in the north) were durable and useful as comestibles on two- and three-day hikes into the hills.

Now from the perspective of a well-nourished historian, I think its fair to say that the reconquest of their homelands by Indians and Pakistanis began at the table, with cooks and bearers and the dishes placed before their new rulers seated at dinner tables in Madras, Calcutta, Bombay, Lucknow, Delhi, and Lahore; in their hill station get-a-ways and in countless other stations on the plains! The charge of South Asian civilization into the West was launched from the kitchens of the Indian and Pakistani restaurants that circle the globe from Anchorage, Alaska, all the way around and down to Wellington, New Zealand. Who would have believed that it was not the ruling khans of the courts and armies but the khansamans, the khans of the household, the cooks, who would turn the tables on the West!

This cookbook fills a huge culture gap for me and others who know Bengal as a province of British India, with its Firpos, Whiteaway Laidlaws on Chowringee Road, the Howrah Station refreshment rooms, and Magnolia ice cream as representative of Bengali cuisine. We were well-acquainted with its flavorful pastries and candy, the curry puffs, ludoos, gulabjamuns and russgullas, and barfi, but the standard curry and rice and the mulligatawny soup of the foreigners table did scant justice to the dining possibilities unexplored. Then there are others who are Bengali, but born and raised in a land far away, who want to re-create the food of their heritage. For them this book offers an answer and tool. For the cook who wants to explore innovative ideas, these original recipes tested and tried in Rinkus kitchen are the answer.

The Bengali Five Spice Chronicles is a welcome guidebook for gustatory explorers both old hands and new. I welcome it and am delighted to have a small role in its launching.

Stanley Elwood Brush

Lumberton, New Jersey

Preface

There is a garden in every childhood, an enchanted place where colors are brighter, the air softer, and the morning more fragrant than ever again.

Elizabeth Lawrence

(from Through the Garden Gate

column in Charlotte Observer)

The garden of my childhood is really the inspiration for this book.

I was born in Kolkata, India, to an adventurous father and a relatively traditional mother, on the cusp of the citys most favorite festival, the Durga Puja, thereby convincing my parents I was blessed. My father was full of energy, enthusiasm, and a strong passion to give his child the best of anything he could afford. He spent most of his time with me, encouraging me to dream, challenging my imagination, prompting me to wish on shooting stars, and at all times encouraging me to follow my interests and hobbies. He taught me to question and reason against the status quo. He introduced me to Rabindranath Tagores work (the Bengali Nobel laureate who has shaped and continues to influence not only Bengali culture but the world at large). The poets collection of music, poetry, and general writings are a guide to understanding nature, seasons, and the general beauty of our Earth. Like the Bard (as Tagore is nicknamed), my father loved India and dreamt of a world that had not been broken into fragments by narrow domestic walls. My father also loved the simplicity of Bengali home food from his childhood. My father and I both shared a love of photography, food, and travel, as well as a deep passion for life and a firm belief that good does triumph over evil.

I get my love of reading and experimental cooking, however, from my mother. My mother had to re-create her home in various parts of the world, and she managed to keep her own Bengali kitchen alive and well, while adapting the best from other cultures around her.

I was also the first grandchild in my mothers family. My maternal grandparents doted on me and were a profound influence on my life. My name is an uncanny by-product of such dotage. When I was born, my grandmother wanted to acknowledge the birth and its coincidence with the Durga Puja by proposing several poetic and religious sounding names. None of these seemed to pass the vetting test of my father and other relatives; the shorter and comparatively modern names proposed by my father did not pass muster either. Luckily, all Bengali children have nicknames, usually referred to as their daak naam (call name). The formal or official name is called their bhalo naam (good name). In fact, how a person is addressed will often tell you about the relationship between the individual and the caller. So for years I was only called Rinku as my daak naam. By the time I started nursery school, they had finally settled on my bhalo naam of Jayeeta, meaning the victorious one. At that point, however, it was too foreign to me and when I went to school, I told everyone my name was simply Rinku. This affinity for simplicity and exerting my independence about my destiny has remained with me throughout my life and it is reflected in my cooking.