Copyright 2022 by Eliza Reid

Cover and internal design 2022 by Sourcebooks

Cover design and illustration Kimberly Glyder

Internal design by Holli Roach/Sourcebooks

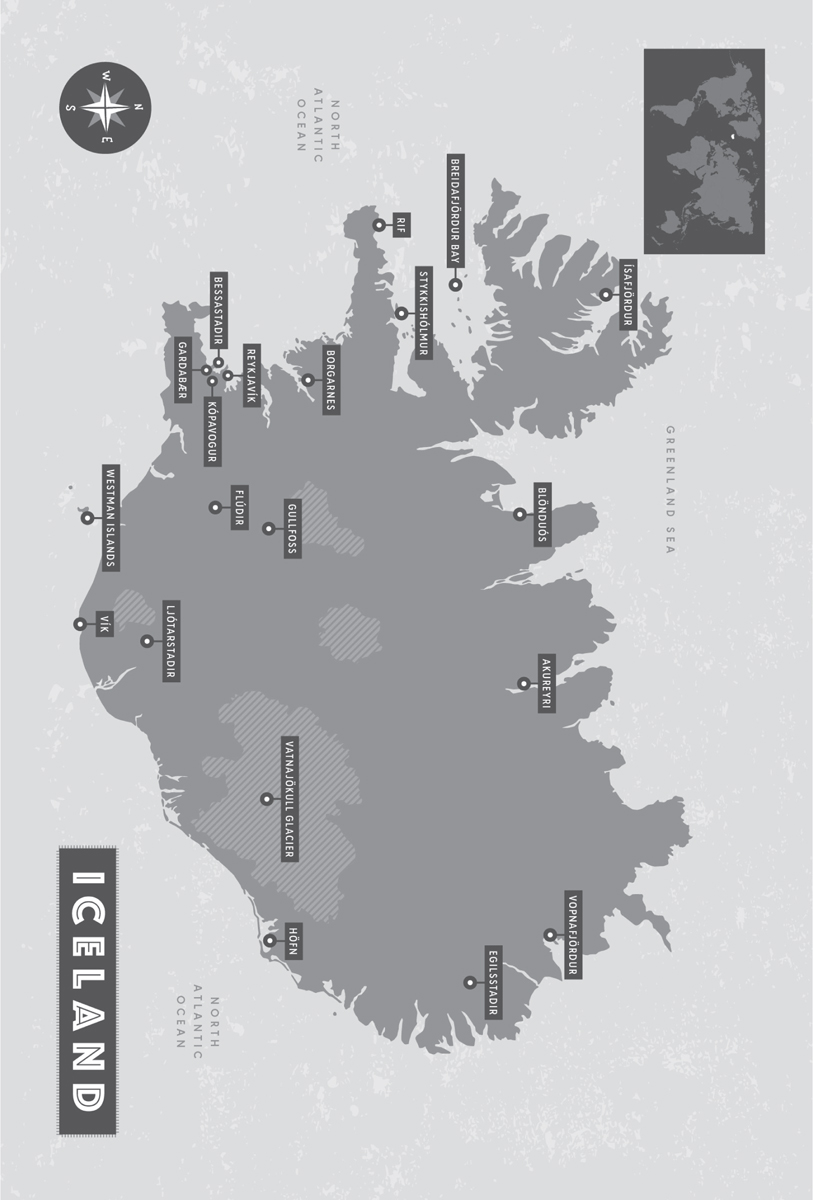

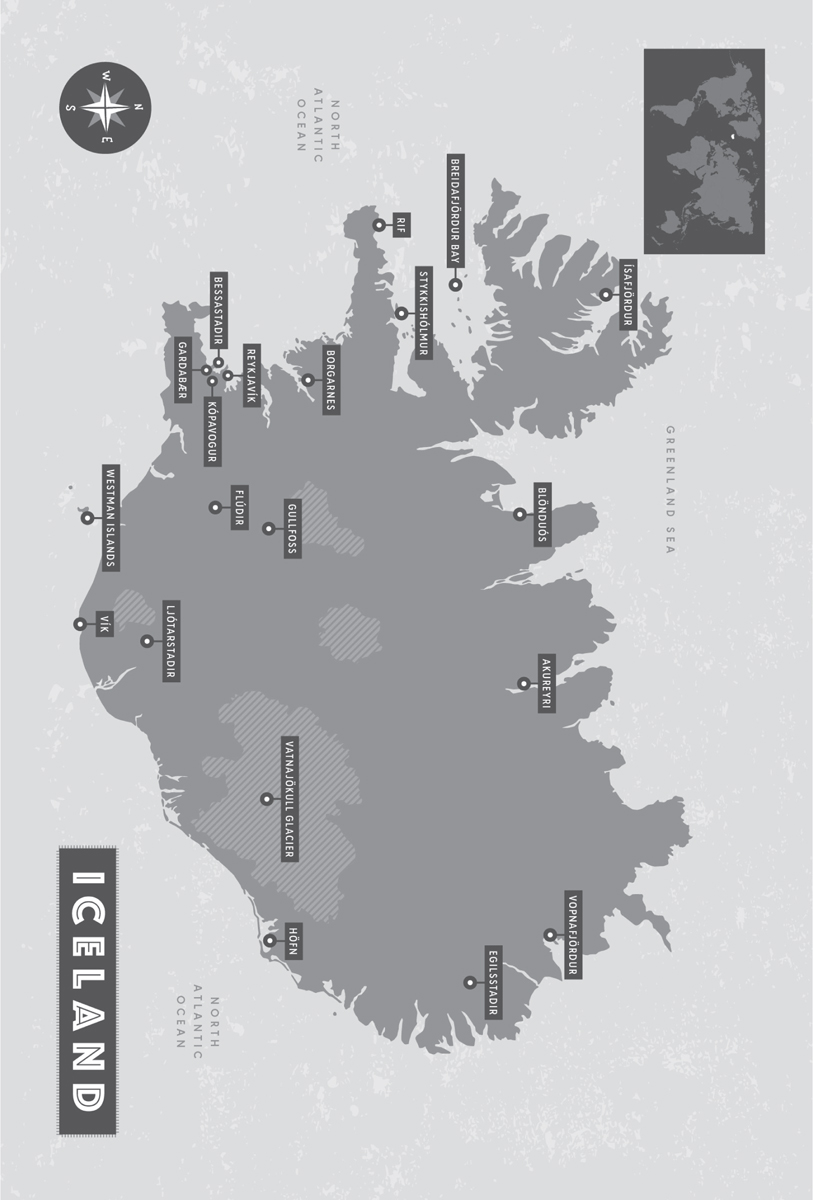

Internal map by Jillian Rahn/Sourcebooks

Internal images Getty Images, redchocolatte/Getty Images, Vectorios2016/iStock

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought.From a Declaration of Principles Jointly Adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations

This book is a memoir. It reflects the authors present recollections of experiences over a period of time. Some names and characteristics have been changed, some events have been compressed, and some dialogue has been re-created.

Published by Sourcebooks

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

sourcebooks.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

SPRAKKAR (plural noun):

An ancient Icelandic word meaning extraordinary or outstanding women

Pronounced: SPRAH-car

(singular: sprakki)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

I AM AN ENTREPRENEUR, AUTHOR , speaker, mother, feminist, and immigrant, and I am married to the president of Iceland. Although there is no formal role titled First Lady, certain duties and functions are expected, if not required, of a spouse of the head of state. As such, my public statements are often analyzed, praised, and critiqued. I have been cognizant of this in the writing of this book.

In Iceland, the role of president is largely, but not exclusively, symbolic. The president is the head of state of Iceland. It is an elected position, and the president has veto power over legislation and can play an influential role in steering the formation of coalition governments. However, it is the prime minister who is the head of the government, and political decision-making from day to day resides within government and parliament. The president (and I, therefore, as a vocal spouse) does not have a political platform or make public statements on budgets, laws, or political strategy for the nation.

In many countries, the issue of gender equality is steeped in politics, affecting legislation that encompasses issues from health care to education. Here in Iceland, however, the debate is no longer whether gender equality is an important objective but how best to achieve it. To paraphrase former American First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, gender equality is a human rights issue, not a political one. I therefore do not see this book as espousing political views. I leave that to the politicians.

This book is a modern portrait of a country and its people using interviews combined with my own fallible memories and impressions. It is neither fully comprehensive nor unbiased. It has not been fed through focus groups, stripped of substance by PR consultants, or varnished to a vapid sheen worthy of what cynics might expect from someone who bears the moniker First Lady. It is, I hope, a testament to the type of society we can build when we are vigilant about creating and ensuring equal opportunities, experiences, and rewards for people of all genders.

A note on spellings: The Icelandic alphabet considers vowels with accents (, , , etc.) as distinct letters, with distinct pronunciations, and I have kept these in the book. Additionally, Icelandic has three letters that are unknown in English: , pronounced aye, which I have kept in this book; , pronounced like the th in although, which I have often replaced with d, as per custom; and , pronounced like the th in think, which I have often replaced with th, as per custom. For example, while I have written Gudni for my husbands name and Thra for the name of the journalist, in Icelandic, these are written Guni and ra.

AN IMMIGRANT IN ICELAND

A guests eyes see more clearly

IN ICELAND, ITS CONSIDERED BAD luck to start a new job on a Monday. A Friday is acceptable, the first day of the calendar month (if it does not fall on a Monday, of course) even better, but if you really want to make a success of your career, avoid starting on a Monday.

My working life on this North Atlantic island therefore began on a Tuesday in October, one that was cloudy with a stiff breeze, as so many October days here are. Having been a resident of Iceland for not quite six weeks, I was unaware of the Monday rule. I was keen to start my new job, but when the CEO of the small software start-up where I had been hired as a marketing specialist gave me the starting date, I felt in no position to suggest an alternative. After all, I was lucky. I had landed a job that related to my previous experience in a country where I did not speak the language and knew practically no one aside from my fianc and his family.

I moved to Iceland for love in 2003 when I was twenty-seven years old. Before I met my future husband, Gudni Jhannesson, in the autumn of 1998, my entire knowledge of the country consisted of being able to recognize its flag and its location on the map and identify its capital city as Reykjavk (thanks to hours playing Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? on a Commodore 64 in the 1980s). I did not know that, even then, Iceland was considered one of the best places in the world to be a woman. That a unique alchemy of history, people, policies, and luck have produced a country that is arguably closer than any other to clutching the golden ring of gender equality.

Gudni and I met in graduate school at Oxford University in England, two foreigners among many at one of Oxfords colleges, St. Antonys, that specialized in international studies. Gudni was the first Icelander to attend St. Antonys and one of only a handful who were studying at the entire university. To me, a twenty-two-year-old Canadian woman who grew up on a hobby farm in the Ottawa Valley, his obscure nationality was alluring. He was quiet, owned many books and few other possessions, and didnt drink as enthusiastically as the other students (I assumed that was what all Icelanders were like). He was also tall and easygoing, and he sparingly but devastatingly deployed a bone-dry, self-deprecating humor to match that of the British.

I had moved across the ocean to England just a couple of months after completing my bachelor of arts degree in Canada, using the excuse of graduate school to experience a new country, get further into debt, and postpone making any decisions about what I actually wanted to do with my life. My cohort fell broadly into two groups. On one hand, there were those who, like me, had been in school all our lives, were hardworking enough to have been accepted at one of the worlds most prestigious institutions, but prioritized our time in an arguably less constructive way (I never missed a pub or poker night and didnt bother to hear then Czech president Vclav Havel deliver a sought-after keynote talk because I knew I would not be tested on it). On the other hand, some students had more maturity. Many had sacrificed much to be at Oxford, quitting jobs, painstakingly saving money, upending families. They were there to get the most they could out of the experience.

Next page