Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Im in fifth grade and my teacher makes a few strange marks on the chalkboard, signs Ive never seen before. Its spring 1986 and, at ten years old, I can barely read. Im a little behind for my age: learning to write was a long and laborious undertaking.

But in that moment my teacher writes something on the boardand without knowing it, she inscribes my future. She was dressed in white, I remember, like the chalk marks on the blackboard. Alpha beta gamma . I tried to decode them. There are only so many moments like this in a life, moments in which some gesture vacuums up the space around you and carries it off into time. The years pass, and your memory warps and skews and often flattens the detailsbut those few scrawlings slashed like the blade of a knife. Thirty years later, I can still hear the chalks staccato sizzle. The Greek alphabet tattooed itself onto my skin. I could never have known that Id spend my life trying to make sense of the worlds illegible signs, why they look the way they do, what they might possibly mean. I could never have known that Id forge a life from trying to decipher.

This is not a book on Ancient Greek, or on the alphabet. Nor is it a history lesson. This book is almost a story about invention, the greatest invention in the world. And I say almost because it has a beginning, and it carries us on a journey around the world, filled with adventure, but the end remains to be written.

The greatest invention in the world. Without it, we would be only voice, suspended in a continual present. The most solid and profound part of our being is forged in memory, in the desire to anchor ourselves to something stable, to persist, knowing well that our time is limited. This book speaks of that urgent need to remain, of the bond we share with others, the dialogue we hold with ourselves. This book recounts the invention of writing.

The protagonists of our tale, however, are not the scripts alone, nor those who discovered or deciphered them. We ourselves are the protagonistsour brains, our ability to communicate and interact with the life that surrounds us. Writing is an entire world to be discovered, but it is also a filter through which to observe our own, our world: language, art, biology, geometry, psychology, intuition, logic. It has things to say about who we are, as human beings capable of feeling, of experiencing and inspiring emotions. This book recounts an uncharted journey, one filled with past flashes of brilliance, present-day scientific research, and the faint, fleeting echo of writings future.

We human beings love to invent stories. Baboons, though no less fascinating than us, spend only 10 percent of their time interpreting, adopting, and imitating others actions. The rest of their time they dedicate to finding food and nourishment. Our percentages are the complete opposite.

We spend an astonishing amount of time trying to understand othersputting ourselves in their shoes, empathizing, acting as a mirror for their emotions and intentions. This tendency has been a major force in the development of our social intelligence. Other factors, of course, have played a role, but we are the only species that uses imagination. Every day we create real, probable, possible, impossible, and absurd scenarios. An infinity of fictions, one layered atop the other.

We create things that dont exist in nature, such as symbols. Along with histories, laws, institutions, governments. All of this is made up. And all of it hinges on the exchange of information: storytelling, forging alliances, establishing and disrupting social equilibriums, gossip.

And yet theres an order to it. Studies of modern hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari Desert or in the Philippines reveal stark differences in the ways they communicate. In the daytime, their discussions revolve around practical matters, location, foodalong with a certain amount of chatter about ones position within the group, climbing the social ladder, competition. Highly personal and logistical matters, nothing fanciful. When they gather in the evening, however, after the hunt, their interactions grow more relaxed. They lower their guard. Seated around the fire, under the light of the moon, they tell stories, they sing, they dance. Their bond grows tighter and stronger.

Thats how it always goes: when we relax, its as if we give voice to our imagination. Dont the best ideas come the moment you stop racking your brain? Think about when youre standing around the office kitchen with your colleagues, or when you call your wife/husband to discuss what/where to eat for dinner, or when you trash-talk your boss. Now think about your evenings, when you coax your children to sleep with a fairy tale, or glue yourself to Netflix, or let it all go at the club or a concert. Think about how, deep down, over the course of hundreds of thousands of years, our communication, and all the structures weve developed to facilitate it, has hardly changed at all.

To prove it, Im going to tell you two overarching stories. Two stories that are very different from each othereach, in turn, containing many smaller stories within it, threads that never intersect. These smaller threads are very similar, they share many ingredients, even if theyre not connected, but the overarching stories are decidedly different. One is filled with detectives, pursuit, aspiration, reward; the other with calmness, time, growth, patience, control. One speaks of unresolved enigmas, the other of inventions. One speaks of attempts and sudden disappearances, the other of plots with happy endings. Youll have little trouble figuring out which is which. At the end of the day, in any case, theyre only stories.

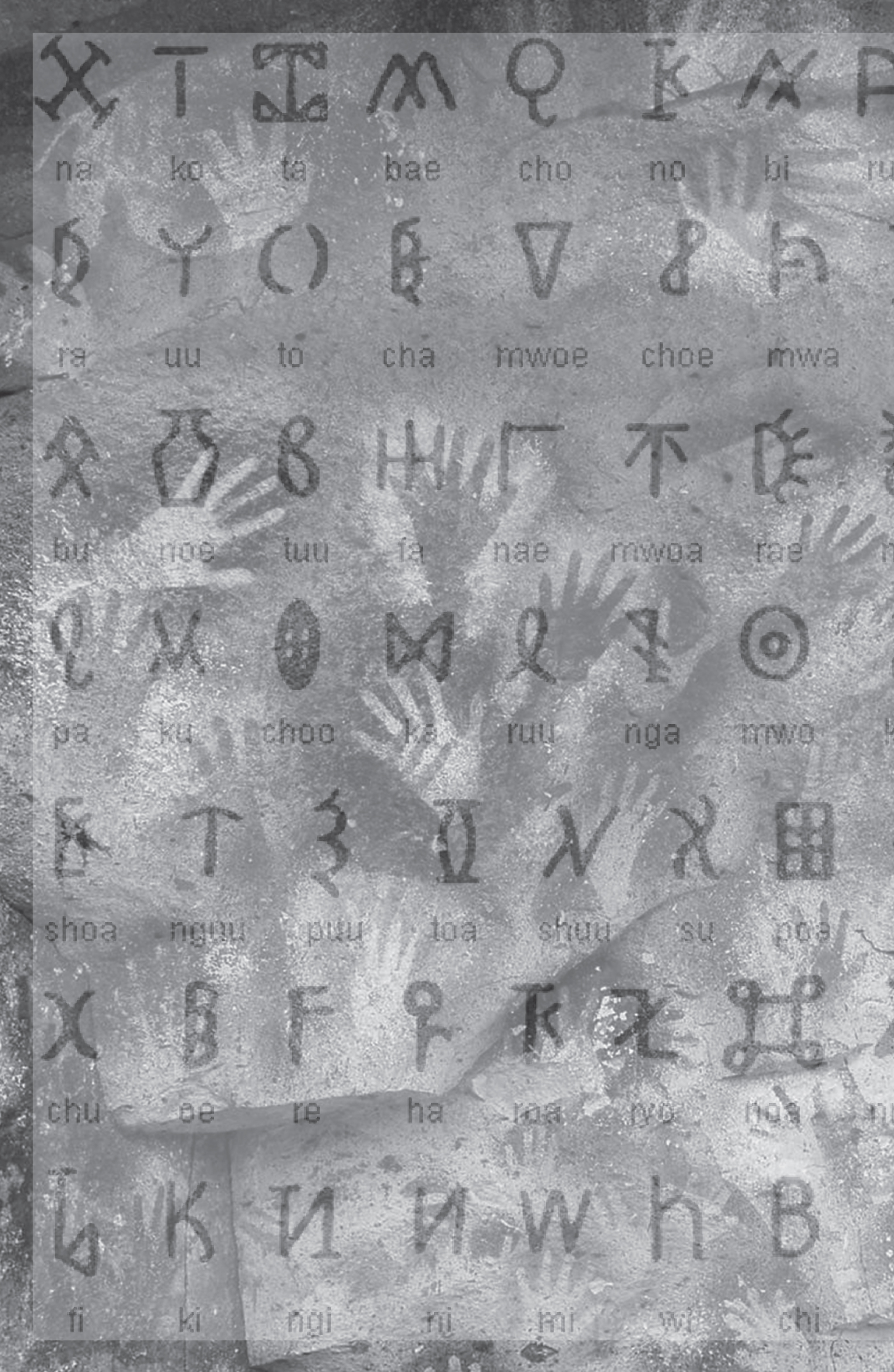

Before we wade deeper into these stories, however, well need to address a few preliminary questions. First of all, it will help to have at least a provisional answer to the question How is a script born? For this, well need to jump back to the beginning beginning, the start of it all. Back, that is, to the moment when symbols were born, when the depiction of a thing became the specific name for that thing. I draw a horse and, if Im able to articulate language (as was Homo sapiens , and perhaps even the Neanderthals, thousands of years ago), I call it horse. Prehistoric art is exquisite, fascinating, highly refined even, but it is enigmatic: the drawing of a horse may very well mean something else. Perhaps it isnt your basic Paleolithic nag, but some creature of the imagination: a hornless unicorn, a wingless Pegasus. Whatever it truly is, well never know. The same enigma that lures us in very happily boots us out.

And even then, a drawing is just a drawingits charged with potential, but ultimately wordless. It remains mute. As have millions of drawings, over thousands of years, in hundreds of different places around the world. The Sumerians, too, five thousand years ago in Mesopotamia, drew objects and numbers on clay tablets.