Copyright 1987 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Sobel, Mechal.

The world they made together.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Afro-AmericansVirginiaHistory18th century. 2. VirginiaRace

relations. 3. VirginiaRace relations. 3. VirginiaHistoryColonial

period, ca. 1600-1775. 4. United StatesCivilization

Afro-American influences. I. Title.

E185.93.V8S64 1987 975.5'00496073 87-3536

ISBN 0-691-04747-2

ISBN 0-691-00608-3 (pbk.)

eISBN 978-1-400-82049-8

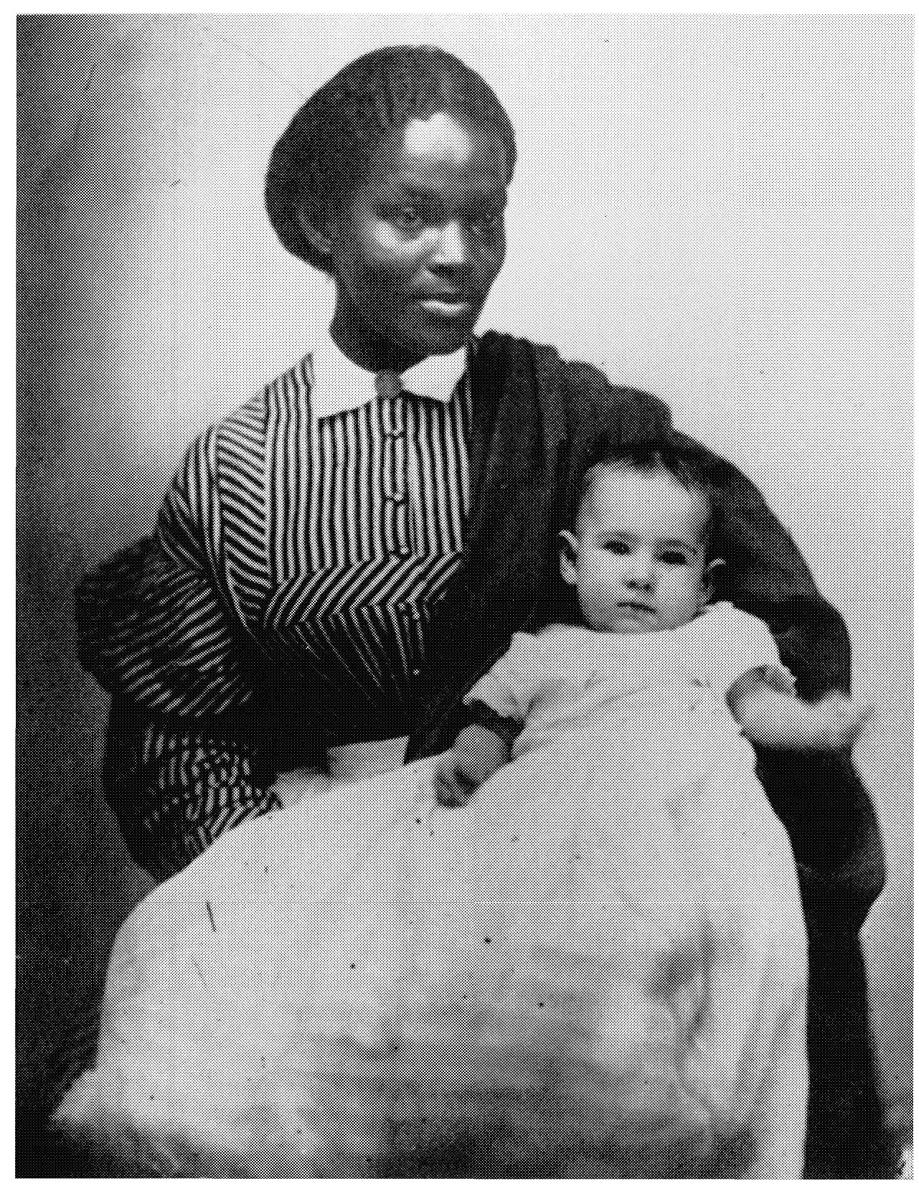

Frontispiece: Photographer Huestis Cook's son and nursemaid, 1868.

Cook Collection. Courtesy of the Valentine Museum, Richmond.

R0

Acknowledgments

I HAVE BEEN at work on the research for this volume for some years and have profited from the advice and help of many individuals. Herbert Klein and William Freedman read an early version of Part One and made significant suggestions. Allan Kulikoff and Ira Berlin read the entire manuscript and wrote extraordinary critiques that helped me revise the book. I owe them both a special debt of gratitude. Gary Nash read a late draft, and his astute criticism improved the volume substantially. Ronald Hoffman, a most generous colleague, gave judicious advice that I have deeply appreciated.

Living as I do, some 6,000 miles from Virginia, I have been dependent on many people for data, microfilm, photostats, and photographs. During a lengthy stay there, I very much appreciated the hospitality of the staffs and the outstanding resources of the Virginia Historical Society, the Virginia Baptist Historical Society, the Institute of Early American History and Culture, and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Members of the staff of the Virginia State Library enabled me to obtain copies of important documents for study abroad. A grant from the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities made possible the purchase of microfilmed records, and the Research Authority of Haifa University generously provided funds to cover typing costs.

For permission to quote from manuscripts in their collections, I am most grateful to the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; the Massachusettes Historical Society, Boston; the Virginia Baptist Historical Society, Richmond; and the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond.

I would particularly like to thank Pat Almonrode, Fred Anderson, Yehoshua Arieli, Selma Aronson, William C. Beal, Richard R. Beeman, Dick Bruggeman, Reginald Butler, Edward A. Chappell, Paul I. Chestnut, Howson W. Cole, Douglas Deal, Helen Doherty, Michael Doran, Daphna Gentry, Harold B. Gill, Lucia S. Goodwin, Anne M. Hogg, William L. Hopkins, James H. Hutson, Judith S. Hynson, Arthur E. Imhof, John E. Ingram, Mary M. Ison, Gregory D. Jeane, Jon Kukla, Heinz Lubasz, Fritz J. Malval, Mark Mancall, Henry Miller, Michael Miller, Richard Newman, Michael L. Nicholls, James O'Malley, L. Eileen Parris, Darett B. Rutman, Vardite Selinger, Elliott Stonehill, Robert Strohm, Thad Tate, Keith Thomas, Robert Farris Thompson, Dell Upton, Charlotte Vardi, Marianna Weissman, David Wiener, Waverly Winfree, Francie Woltz, Gordon E. Wood, Michael Zuckerman, and Shomer Zwelling. Yoshiko Fukakusa was of great help in checking difficult bibliographical references. I am grateful to Genoveba Breitstein, who typed several versions of this work with skill, speed, and understanding. I also wish to give special thanks to my editor, Gail Ullman, who was very patient, supportive, and helpful, and to Cathie Brettschneider, whose fine editorial skills improved the manuscript.

My husband Zvi and my son Noam have both lived with this project for all the years I've been involved in it. They have probably learned more about Virginia and slavery than they wanted to know, but their willingness to listen and respond has been very important, and I learned a great deal from them. Certain interests of my older childrenparticularly Daniel's in the building of houses and Mindy's in spiritual traditionshave had their effect on me as well. To them all, my thanks.

It is not at all pro forma that I emphasize that no one who has read this work and/ or helped me along the way agrees fully with the views presented here. In fact, fairly often I have come to opposite conclusions from those voiced by the very authorities I rely on for evidence, so that citations in the book often refer to those with whom I differ but whose evidence I have used. I'd like to ask their indulgence and to thank them too.

The World They Made Together

It was like the garden of the Lord,

like the land of Egypt.

Genesis 13:10

Introduction

M ANY YEARS ago, when I began to consider the First Great Awakening in the South, I was taken aback by the clear evidence of extensive racial interaction.

I am now convinced that the Southern Awakenings were a climax to a long period of intensive racial interaction, and that as a result the culture of Americansblacks and whiteswas deeply affected by African values and perceptions. The interpenetration of Western and African values took place very early, beginning with the large-scale importation of Africans into the South in the last decades of the seventeenth century. In the eighteenth-century South, blacks and whites lived together in great intimacy, affecting each other in both small and large ways. They lived in the same houses as well as in separate houses that were more often similar than not; they did much the same work, often together; and they came to share their churches and their God. Their interaction was intense and continued over the lifetimes of most blacks and whites. In spite of a significant interpenetration of values between the two races, the whites were usually unaware of their own change in this process. Nevertheless, in perceptions of time, in esthetics, in approaches to ecstatic religious experience and to understanding the Holy Spirit, in ideas of the afterworld and of the proper ways to honor the spirits of the dead, African influence was deep and far-reaching.

This interpretation is based upon an analysis of the social history of eighteenth-century Virginia, the largest and most populous colony and home for a significant number of emigrants to virtually all the later settlements. In Virginia the racial balance was such that most whites were in both intensive and extensive contact with blacks. In 1700 some twenty-five percent of the population was already black; by mid-century sixty-six percent of the Tidewater area, the most heavily settled section, was black. This change was rapid and radical. Living through it, William Byrd II thought Virginia would become known by the name "New Guinea," and he and others came to fear the social results of the demographic transformation..)