Fordham University Press gratefully acknowledges financial assistance and support provided for the publication of this book by the Rutgers University Research Council.

Copyright 2021 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020919016

First edition

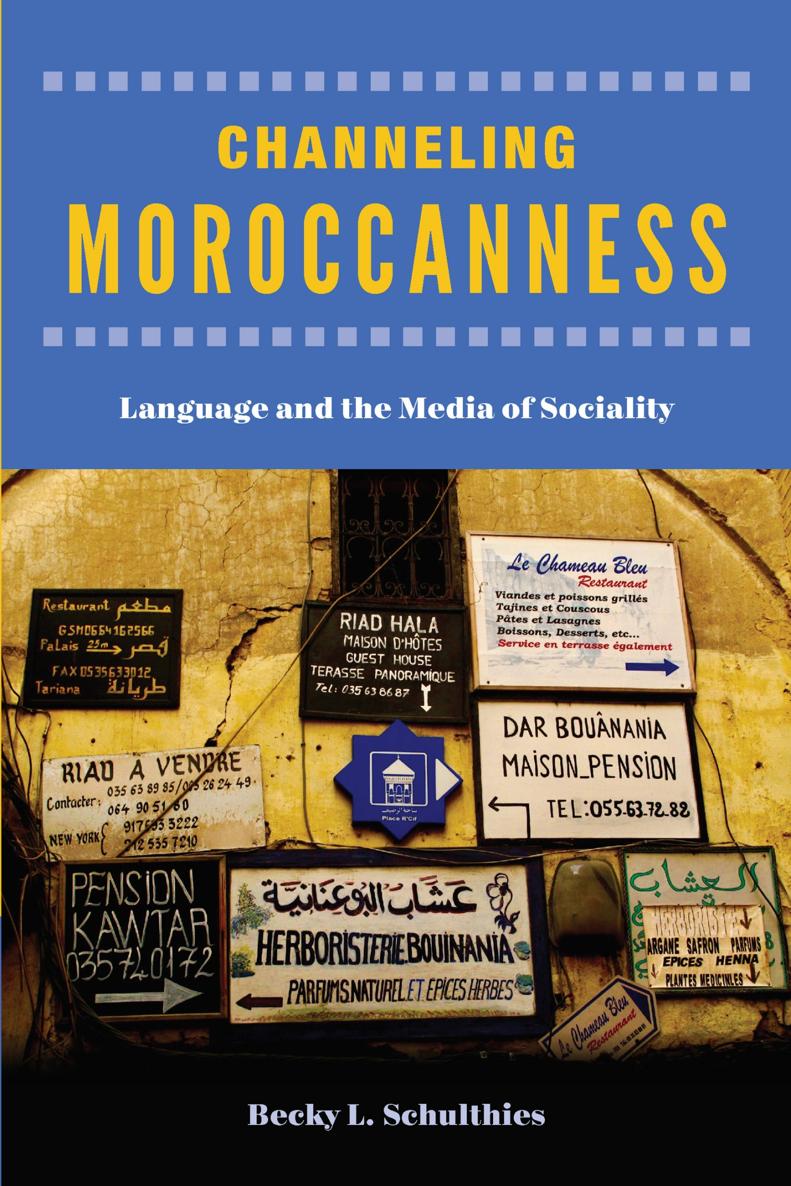

I owe a great debt to my many Fassi colleagues and friends for allowing me to record, assisting me with transcription, and clarifying my understanding of many hours of recordings and observations. I based the transliterations in this text on my understanding of Moroccan ways of speaking, using the International Journal of Middle East Studies (IJMES) transliteration key. However, the transcriptions are my Moroccan contributors understandings of how to write Moroccan spoken and written forms, and as of this book points out, orthographic heterogeneity was common in everyday Fassi practices of writing their ways of speaking. So dont be surprised if you find variability in the transcriptionsit reflects the writing practices of the Fassis I wrote about in this ethnography.

An Arab student of mine pointed out that the use of the term Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) vs. alfu was an educational shibboleth; it demonstrated what kind of Arabic training one had. Instead of using my own terms, I opted throughout this book to use Fassi terms for the main language forms I analyzed: larabya (Arabic) often contrasted with franais (French), darja (Moroccan Arabic) often contrasted with fu (formal literary Arabic). But these were not fixed registers: they were classifications that did important social work, as you will soon read.

Arabic Letters | | IJMES Transliteration | | Phonetic Value (IPA) |

|---|

[] |

[] |

b | [b] |

t | [t] |

th | [] |

j / g / | [] / [] / [g] |

H | [] [] |

kh / x | [X] |

d | [d] |

dh | [D] |

r | [r] |

z | [z] |

s | [s] |

sh / | [] |

[] [s] |

[] [d] |

[] [t] |

[] [D] |

/ | [] |

gh / g | [] |

f | [f] |

q / | [q] |

k | [k] |

l | [l] |

m | [m] |

n | [n] |

h | [h] |

w / u: | [w] / [u:] |

y / i: | [j] / [i:] |

CHANNELING MOROCCANNESS

:

Episode 1: Remote Control Prayerbeads

I daily found myself part of early evening assemblages in Fassi homes,or , atya time to unwind from the days labors and reaffirm sociality bonds with family, neighbors, and friends through food and conversations about any- and everything. Though anthropologists have written how French colonial work schedules (Kapchan 1996, 15455), cafculture (Graiouid 2007), media technologies (Davis and Davis 1995), and citizen-consumer aspirations (Newcomb 2017, 11620) have shaped Moroccan tea gatherings, some Fassi families preserved this as an important vestige of Moroccan heritagehow their mothers, grandmothers, and aunts cared for and facilitated their social networks (Fernea 1975; MacPhee 2004; Mernissi 1994; Newcomb 2009). Since my first Moroccan fieldwork ventures in the early 2000s, the profound everyday quality of this recurring sociality ritual had piqued my ethnographic interest in the connections between electronic mass mediation of Moroccanness and talk about it. I learned the way to make and pour tea so that the bubbles foamed properly in the glass; the respectful ways to reach across the table and tear off appropriate bread pieces to dip in olive oil or spread with Le Vache Qui Rit cheese; how many sweets or boiled egg halves to take so as to not appear greedy; what kinds of television programs backgrounded the relaxed teatime atmosphere; and the patterns of talk that could accompany these domestic interactions.

During one particular teatime gathering I recorded and transcribed, a mother, her two teenage daughters, their male cousin, and female neighbor had been flitting across television channels and chatting for the better part of an hour. The daughters had just returned from school, the women were resting from domestic responsibilities, and the cousin was taking a break from studying for his university classes. The remote was in the hand of the fifteen-year-old daughter, who continually moved between transnational satellite stations. She had been flipping between an Egyptian music video station and a Bollywood movie channel. Her sister, mother, and older cousin each asked her to change to a different station, but she ignored their requests. No one immediately protested her disregard, conveying a sense of languid easebeing together was the purpose of watching, no matter the programming. At one point the younger sister began singing the song attached to one of the videos flashing by, and the mother clicked her tongue in exasperation. She followed this with a critique couched in a religiously significant metaphor: (l awl wal qwat l bllah, There is no power or strength except in God.) I often heard this phrase used in Fez and Morocco more generally to express awe, frustration, empathy, encouragement, anxiety, pietya range of sentiments that could only be fixed in the context of the utterance. In this instance, the mothers voice quality began with a breathy intake and dropped pitch rapidly as she expelled the phrase, signaling repetitive use and a tone of resignation tinged with sarcasm. She was mildly frustrated with the lack of a specific program. The younger sister further affirmed her mothers evaluative stance toward this practice of montage viewing, extending the critique with the commonly accompanying phrase