i ND i A SOC i AL

HOW SOCIAL MEDIA IS

LEADING THE CHARGE AND

CHANGING THE COUNTRY

ANKIT LAL

First published in India in 2017 by Hachette India

(Registered name: Hachette Book Publishing India Pvt. Ltd)

An Hachette UK company

www.hachetteindia.com

Copyright 2017 Ankit Lal

Picture on page 112 courtesy the Delhi Commission for Women.

Pictures on pages 118 and 123 courtesy Stop Acid Attacks.

Ankit Lal asserts the moral right to be identi ed as the author

of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system (including but not limited to computers, disks, external drives, electronic or digital devices, e-readers, websites), or transmitted in any form or by any means (including but not limited to cyclostyling, photocopying, docutech or other reprographic reproductions, mechanical, recording, electronic, digital versions without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by him. The publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders and obtain permission to reproduce the images used in this book. For those images whose sources we have been unable to trace, we advise the copyright holder to contact us so that we may appropriate credit in future editions.

Print edition ISBN 978-93-5195-212-1

Ebook edition ISBN 978-93-5195-213-8

Hachette Book Publishing India Pvt. Ltd

4th & 5th Floors, Corporate Centre,

Plot No. 94, Sector 44, Gurugram 122003, India

Cover design by Haitenlo Semy

Cover image Getty Images

Originally typeset in Minion Pro 11/13.9 by

Manmohan Kumar, New Delhi

This book is dedicated to the millions who hit the streets

for Jan Lokpal and Nirbhaya.

Viva la democracy!

CONTENTS

On the night of 26 November 2008, while most of us were glued to our television sets watching an India-versus-England cricket match, yellow inflatable boats carrying ten men were moving quietly towards a fishermans hamlet near Colaba at the southern tip of Mumbai. These ten men, including 21-year-old Ajmal Kasab, were part of the terrorist organization Lashkar-e-Taiba. They had undergone a year of rigorous military training in secret camps in Pakistans Muzaffarabad, before being sent to the port city of Karachi where their handlers had given them their target Mumbai. Now, armed with lethal AK-47s, pistols, ammunition, grenades and other explosives, as well as timers, maps and a GPS unit, they were coming to shore with only one motive to lay siege to the city that never sleeps.

The Leopold Caf, a popular Iranian restaurant and bar frequently visited by foreigners, on the Colaba Causeway in South Mumbai, was one of the first sites to be attacked. Around 9.30 p.m., two men entered the caf and opened fire, killing at least ten people and injuring many more. The Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CST) railway station was also attacked around the same time, where two men entered the passenger hall and used their AK-47s to shoot indiscriminately, killing 58 people and injuring 104 others. The attackers then fled, firing at pedestrians and police officers on the way, killing a few of them.

Sourav Mishra who was relatively new to Mumbai in 2008 and had recently started working as a journalist at Reuters was at the Leopold Caf on the evening of the attacks with two French friends. When the terrorists hit the caf, a grenade landed at a table near him, flinging him off his chair, before a bullet hit him as he tried to rush out.

I heard what seemed like a blast and something hit me hard on my back. I panicked and ran out through the nearest door, Mishra says, nearly ten years later. Kishore, a hawker on Colaba Causeway, found him injured on the street and took him to a nearby hospital, where he was given preliminary treatment. After he was moved to another hospital in Vashi the next morning, he was told that a rib fracture had prevented the bullet from puncturing his lung. He had to undergo surgery to have the bullet removed.

Two of the citys most iconic hotels, the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel and the Oberoi Trident, were also targeted over the course of the next 60 hours. Six explosions were reported at the historic Taj one in the lobby, two in the elevators, three in the restaurant and one at the Trident. The Nariman House, a Mumbai landmark that housed a Jewish Outreach Centre run by Gavriel and Rivka Holtzberg, was also attacked, and six of its occupants (including Holtzberg and his wife) were killed.

Today, it would

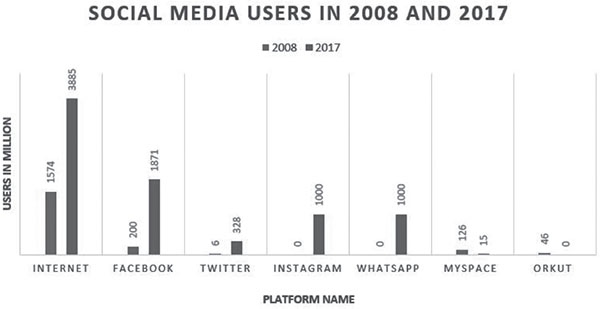

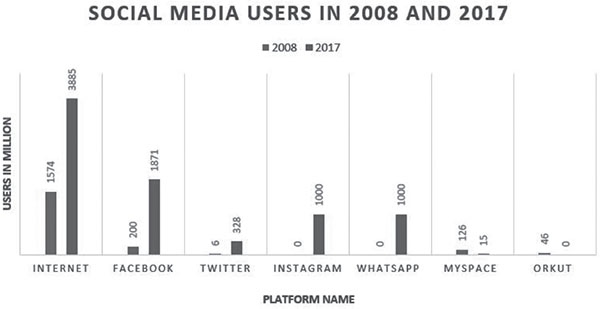

Facebook was also relatively new, and only taking baby steps in India back in 2008. In May of that year, Facebook surpassed MySpace in worldwide unique visitors WhatsApp didnt even exist in 2008; it was launched in January 2009.)

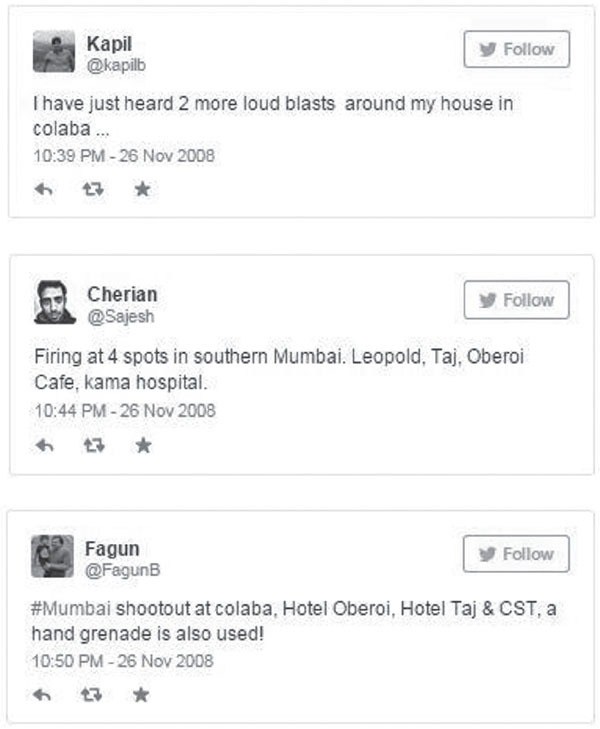

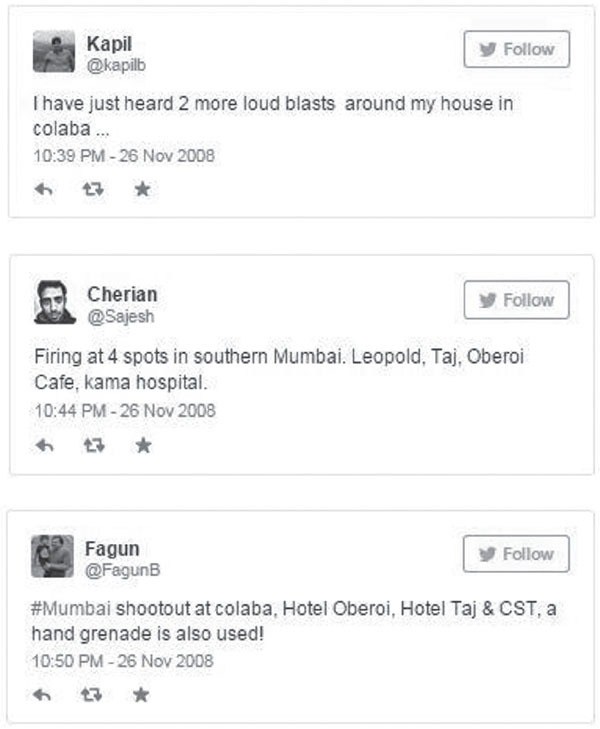

On 26 November 2008, one of the earliest tweets about the attacks came from an advertising professional called Kapil Bhatia (@kapilb), who started talking about them at 10.25 p.m., much before any media house or news agency had any credible information. In the next 20 minutes, more people began to tweet about the attacks, mentioning the places where the firings had taken place.

I asked Shaili Chopra, one of the journalists who had covered the Mumbai attacks for NDTV, if social media was a source of information during the Mumbai attacks. Heres what she had to say: That was not really the time we knew or understood that social media could be used on such occasions. All we had in the name of smartphones were Blackberries and the Blackberry social media apps were not very easy to use.

The concept of a hyper-connected virtual world, which we take for granted today, hadnt come to India at the time. It was only because Mumbai was one of the most prosperous cities in the world, and the attacks happened in the most elite locality of the city, that social media then the recourse of the rich, as suggested by smartphone penetration at the time was abuzz. For the first time in India, social media took centre stage and became one of the key sources of information dissemination about the attacks. Take, for instance, journalist Vinukumar Ranganathan who uploaded around 200 pictures from around his house in Colaba where the majority of the attacks had happened on to his Flickr account. He also tweeted the link to his photographs from his Twitter handle (@Vinu). His photos were consequently picked up by several broadcasters and published across the globe.

Vinu, like the others who were active on social media at the time, was hounded by the media after the attacks so much so that he started to avoid talking about the attacks altogether. When I contacted him asking for an interview, he simply directed me to whatever information was available in the public domain.

But it was not information about the attacks that fuelled social media. Citizens were waking up to the ability of social media to coordinate movements and bring much-needed focus on issues that mattered. The Mumbai attacks were probably the first time that a citizens movement came alive on social media in India, and was executed in the real world. A local group of bloggers turned its blog titled Metroblog into a newswire service, collating all kinds of information about the attacks from different platforms from poems and personal blog posts to video interviews of people like Ratan Tata. During the 60 hours of the attacks, more than 30 posts were uploaded on the blog, the first posted at 11.07 p.m. on 26 November. Another blog, MumbaiHelp, offered help to users trying to get through to their family and friends. They also put together a list of helpline numbers and posted them on their blog. Blood donation drives began to organize themselves on cyberspace, and helplines were posted for people looking to contact hospitals for more information about their loved ones. Facebook groups and events, still nascent at the time, were created to organize events like candlelight processions and congregations in the aftermath of the attacks.

Next page