Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

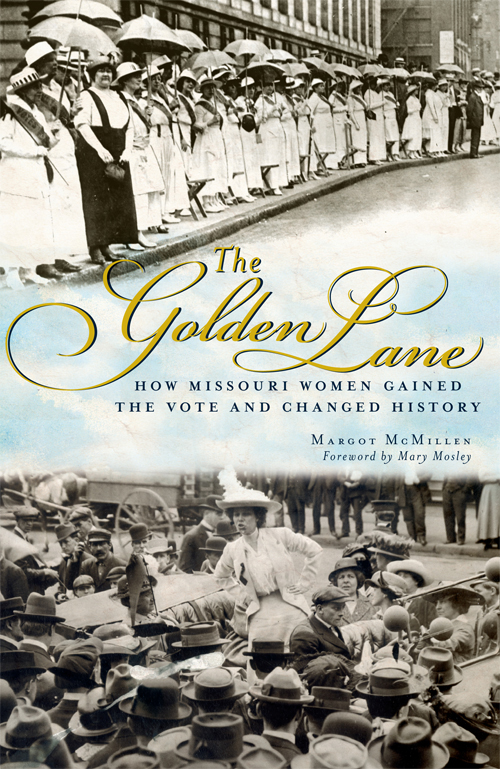

Copyright 2011 by Margot McMillen

All rights reserved

First published 2011

e-book edition 2011

ISBN 978.1.61423.086.1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McMillen, Margot Ford.

The golden lane : how Missouri women gained the vote and changed history / Margot

McMillen.

p. cm.

print edition: ISBN 978-1-60949-013-3

1. Women--Suffrage--Missouri. 2. Women--Missouri--History. I. Title.

JK1911.M8M36 2011

324.62309778--dc22

2011012903

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Research is never finished; it is only abandoned. And, then, its dedicated.

I dedicate this work to my daughters, Holly and Heather Roberson, and to

my mom, Nan McMillen. Explorers of new places, we hold the lanterns

for one another.

Contents

Foreword

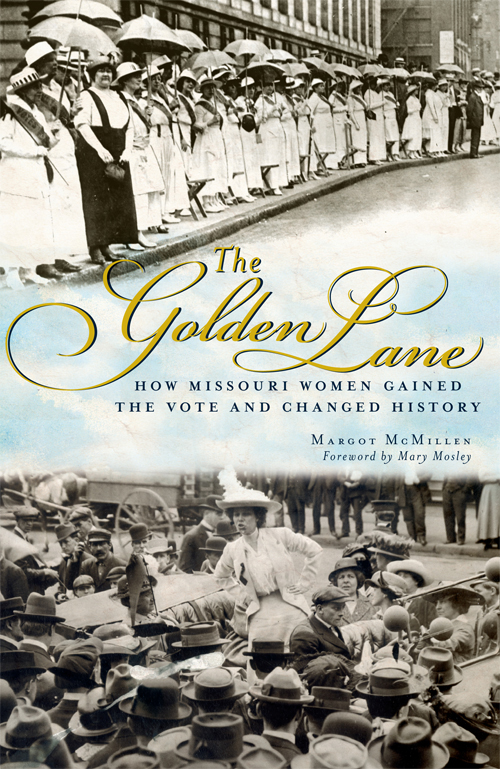

Typically, when women walk into the voting booth, we dont think much about how we got the right to vote or the women who fought for it. We assume we have always had voting rights and always will. Partly, this is a consequence of not knowing enough about our history. In this volume, we learn the part that Missouri women played in winning the right to vote; it is a valuable addition to our knowledge of the history of womens suffrage.

Today, many politically active women are concerned that younger women are not exercising the right that women fought for so long and hard to obtain. Indeed, less than half of women under the age of thirty who are eligible to vote do so. Nevertheless, they vote in greater numbers than young men. Since the 1970s, the gap between young female and young male voters has increased from two percentage points to nearly seven in 2004. In fact, since 1980, more women than men of all ages have voted in national elections.

One of the arguments against womens suffrage a century ago was that women were not politically aware enough to vote intelligently and would take the country in the wrong direction. The opposition to womens suffrage included the liquor and brewing industries in particular, since women were the backbone of the temperance movement. Other opponents to womens suffrage were business and industry, which wanted a cheap, docile labor force, and many southern senators, who were afraid the new electorate would upset the racial status quo.

Have their fears proven true? In some measure, yes. By 1980, it had become apparent that there was a gender gap between male and female voters. The gap favored Democrats. In 1980, the gap between men and women voting for Ronald Reagan was eight percentage points. By 1996, the gender gap had risen to its all-time high of eleven percentage points. In effect, women elected President Clinton. Again, in 2008, women made the difference in the Obama-McCain race, with a gender gap of seven percentage points.

Today, some still worry about how women vote. Right wing political pundit Ann Coulter has said that she has a fantasy of disenfranchising women because they elect Democrats. John Lott, another right-leaning commentator, blames female voters for the rise of big government and government spending, which he says started in 1920, when women began voting. He says one of the reasons for this is that women have greater interest in government solutions to social problems.

Many people believe that most women thought suffrage would give them equality, so after 1920 they stopped working for womens rights. But Alice Paul, head of the suffrage group known as the National Womans Party, wrote the Equal Rights Amendment. Introduced in Congress in 1923, it languished there until the 1970s, when women disrupted a Senate committee hearing to demand a vote. Though it passed Congress by a large margin in 1972, it has been ratified by only thirty-five of the thirty-eight states needed for it to become part of the U.S. Constitution.

Writers often use the passive voice when talking about womens suffrage: women were given the right to vote. This language obscures the many years of womens work organizing, petitioning, lobbying, parading, picketing the White House and, finally, being imprisoned and force-fed. This book not only documents Missouri womens part in that struggle but also apprises us of the names of many of the women whose contributions would otherwise have been forgotten. This history should inspire all women to exercise that right so dearly won.

Mary Mosley

March 12, 2011

William Woods University

Acknowledgements

We look back and assume that womens history is the same as mens. In fact, our educations encourage us to think that way, and our books are filled with the stories of great deeds by great men, events where we think we played a part. In fact, women were often excluded from stage front. Rather, when men had a war, women cared for the wounded. When men built a business, women worked in the lowest-paying jobs.

But things change, and if we are lucky, we live long enough to see it. This book is about one giant change that took generations. I hope it increases understanding for those who, today, are working so hard against huge odds in the mere hope that they can make things better. Courage, friends. Because of work for the better, women have infinitely more possibilities than they did a generation ago. It is a mark of success that todays women can take for granted the right to vote, to be educated, to work at a satisfying job.

This book is for people who wish to understand womens courageous history. In writing it, I have learned a lot, and I have many people to thank. In the summer of 2010, three groups of writers read drafts of these pages. Thank you to Karen Barrow, Sarah Fast, Vera Gelder, Julie Kapp, Shirley Kidwell, Debra Kirchoff, Edie Maxey, Libby Peters and Gretchen Seifert. I also owe a great debt to the keepers of the collections of Missouris many archives: Sue Rehkopf at the Archives of the University City Public Library, Ellen Thomasson of the Missouri History Museum and Greg Olson of the Missouri State Archives. Thank you also to Kimberly Harper of the Missouri State Historical Society for directing me to the story about the American Womans League.

And to my final readers, Pippa Letsky and Howard Wight Marshall: you are the best.

The Golden Lane

It was June 14, 1916; a warm, sticky Wednesday morning. The Democratic Convention would soon meet in St. Louis, at the Coliseum, the worlds largest convention center. Inside the Jefferson Hotel, the men ate breakfast and met with their committees. Perhaps they chatted about the war in Europe, noted that Woodrow Wilson had the election locked up or remarked that the bread was darn fresh. The freshness of the bread might have led to praise for the city, with its modern lights and purified water, skyscrapers and electric streetcar system. Delegates might even have expressed surprise, comparing St. Louis to cities on the East Coast, the West Coast and, of course, its Midwest rival, Chicago.

Next page