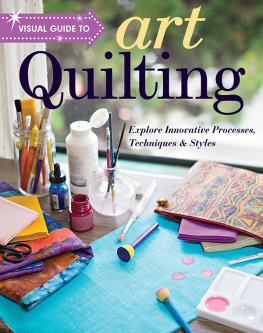

Publisher Amy Marson Creative Director Gailen Runge Acquisitions Editor Roxane Cerda Managing Editor Liz Aneloski Project Editor Alice Mace Nakanishi Compiler Lindsay Conner Cover/Book Designer April Mostek Developmental Editors Liz Aneloski, Cynthia Bix, Jake Finch, Lynn Koolish, Terry Martin, Karla Menaugh, Deb Rowden, and Kesel Wilson Technical Editors Carolyn Aune, Helen Frost, Rebekah Genz, Robyn Gronning, Ann Haley, Ellen Pahl, Sandy Peterson, Gailen Runge, Alison M. Schmidt, Teresa Stroin, Elin Thomas, Julie Waldman, Del Walker, and Nanette S. Zeller Production Coordinator Tim Manibusan Production Assistant Jennifer Warren Indexer Managed Editing Illustrators Tom Allen, Freesia Pearson Blizard, Jenny Leicester Davis, Zinnia Heinzmann, Jessica Jenkins, Tim Manibusan, Chris Pasquini, Kirstie L. Pettersen, Aliza Shalit, Richard Sheppard, and Gregg Valley Cover photography by Lucy Glover of C&T Publishing, Inc. Interior photography by Nissa Brehmer, Christina Carty-Francis, Luke Mulks, Cara Pardo, and Diane Pedersen of C&T Publishing, Inc., unless otherwise noted Published by Stash Books, an imprint of C&T Publishing, Inc., P.O. Box 1456, Lafayette, CA 94549 Chapter 1: Design Theory and Inspiration Introduction BY JANE DVILA AND ELIN WATERSTON Within the past few decades, the quilt industry has matured as people have mastered traditional skills and designs.

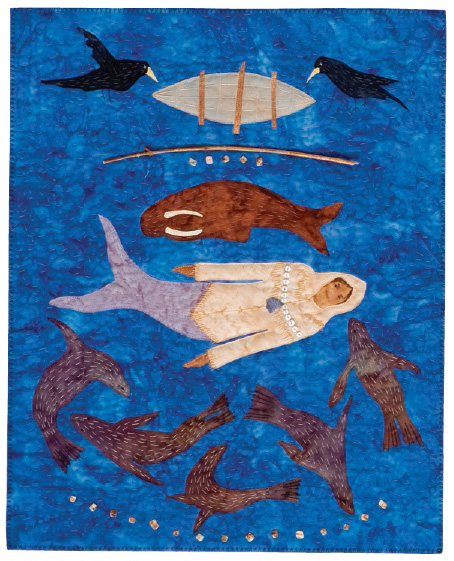

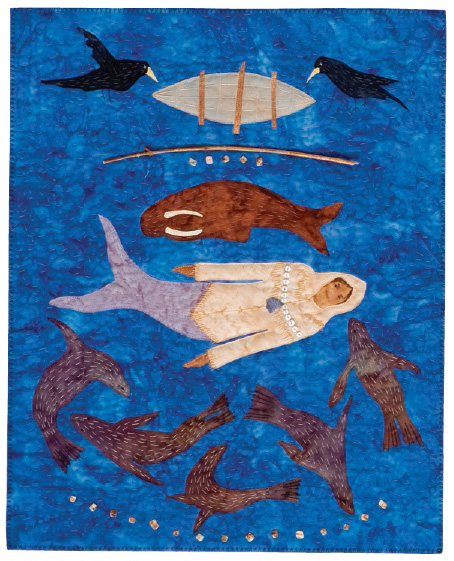

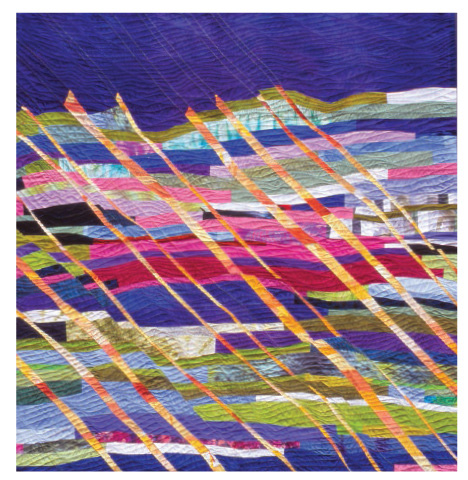

Some quilters have begun to look beyond traditional patterns and techniques. Although there is nothing wrong with and much to be said for making quilts to cover beds, there comes a time to step outside the box and explore the convergence of quilting and art.  Sedna, by Elin Waterston While technical workmanship and skills are important in art quilting, a good grasp of design is equally important, as is a willingness to experiment with composition and materials. Art quilting is both art and quiltingboth aspects should be balanced, and yet the definitions of each should be stretched. We hope that this book will give you a foundation in the basics of good design, show you some techniques to use in your work, help you to develop a personal style, and show you what comes next in the process of becoming an art quilter. Take what you learn and make it your own.

Sedna, by Elin Waterston While technical workmanship and skills are important in art quilting, a good grasp of design is equally important, as is a willingness to experiment with composition and materials. Art quilting is both art and quiltingboth aspects should be balanced, and yet the definitions of each should be stretched. We hope that this book will give you a foundation in the basics of good design, show you some techniques to use in your work, help you to develop a personal style, and show you what comes next in the process of becoming an art quilter. Take what you learn and make it your own.

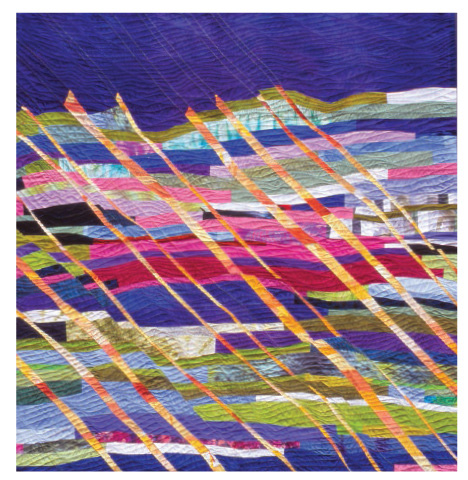

The Main Idea or Theme BY ELIZABETH BARTON The first step in creating any art is to figure out what the main idea is. What do you want to make a quilt about? What has caught your eye or your heart? It can be something small, like a bowl of cherries or a few leaves dancing in the wind with the light shining through; it could be the feelings of joy at the birth of a child or horror at war; or it could be a fascination with mathematical puzzles or with the way words look on a page. It can be depicted in a realistic, representational, or quite abstract manner. Dont feel that you have to decide how youre going to show the main idea right away. Trying to think about how youll take the fifth step when youre only taking the second one can lead to stumbling.  Idea of a City, by Elizabeth Barton, 60 60

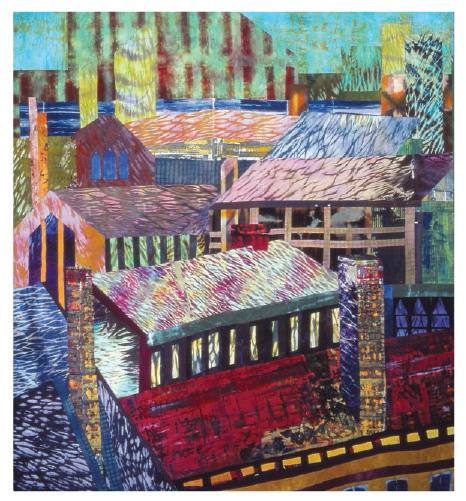

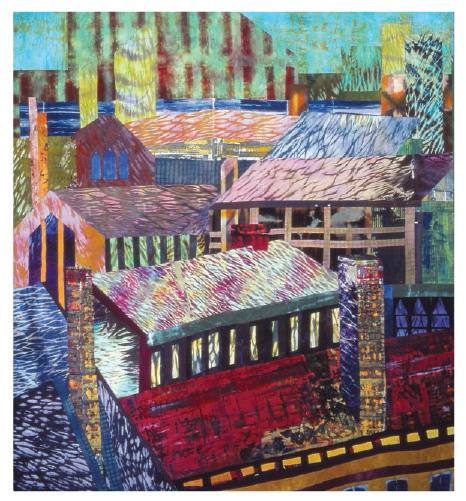

Idea of a City, by Elizabeth Barton, 60 60  From the Top, by Elizabeth Barton, 45 46

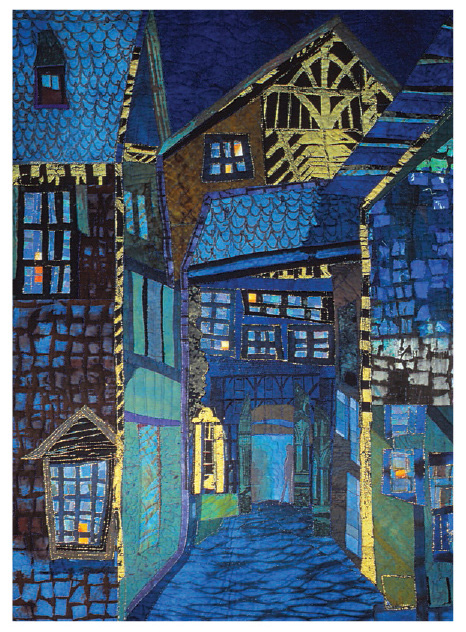

From the Top, by Elizabeth Barton, 45 46  Pump Court, by Elizabeth Barton, 35 48 Photos by Elizabeth Barton So think before you set out: What are you trying to convey? What is the experience that you want? Almost every other decision you will make about the piece will be informed by the main idea.

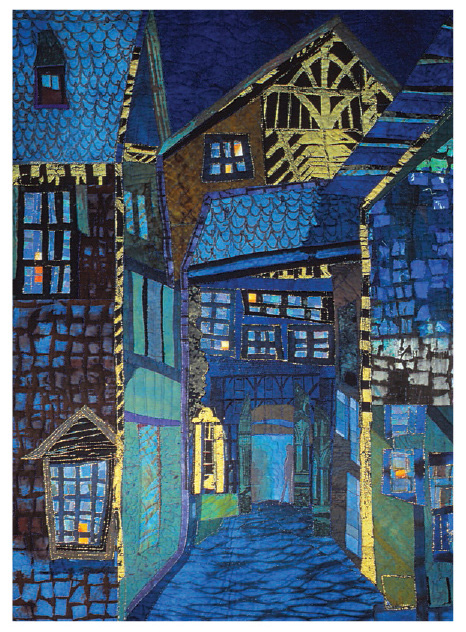

Pump Court, by Elizabeth Barton, 35 48 Photos by Elizabeth Barton So think before you set out: What are you trying to convey? What is the experience that you want? Almost every other decision you will make about the piece will be informed by the main idea.

Rememberit can be realistic or completely abstract. Beatle George Harrison opened one of his mothers romantic novels and began a song from the phrase gently weeps that caught his eye. I made the quilt Pump Court because I was thinking about the little alleyways in my hometown and how much they revealed the age and the medieval character of the city. I cast a blue light over the piece by overdyeing it, which I hoped would make it a little more distant and mysterious. In her book The Creative Habit, choreographer Twyla Tharp wrote, Every work of art needs an underlying theme, a motive for coming into existence. Think about it: What are you trying to say? What is your intention? It is so helpful to clarify your goals for the piece at the beginning.

Tharps term for the main idea is the spine of the piece. (I highly recommend her book, by the way.) QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF ABOUT THE INSPIRATION After you have collected photographs and pictures and notes on music, poetry, or walks in the woods, analyze what it is about this source material that attracts you. Lets assume, for right now, that it is a visual inspiration (though it doesnt have to beall senses can inspire us to create art). Looking at the inspirational photograph, ask yourself the following questions. Remember that what intrigued you could be more than just one thing. It doesnt have to be world shattering.

Adjust the questions accordingly if your inspiration is an experience, like riding a white horse along the beach or listening to a piece of music. Sit quietly in front of the inspirational image, think, and ask yourself these questions: What in this image seized my eye? The shapes? The colors? The lines? The contrast of light and dark? The texture? What is the main idea I want to make a piece about? Which parts of the inspiration are most relevant to the main idea and therefore important to include? And more importantly, which can, and therefore should, be left out? Michelangelo supposedly said that he took a block of marble and chipped away what he did not want, revealing his sublime inspiration. Now Im not suggesting that we can all be Michelangelos; however, its often what is not included that is the most important. Making a piece of visual art is a bit like writing a poemevery element should be crucial to the finished piece, and nothing extraneous should be included. Going back again to your inspiration, here are a few more questions: Will other elements need to be added? How and where can more pizzazz/oomph/ excitement be added in order to make the final work sing? It isnt necessary to find the answer to this final question before you start, but keep it in mind. And as you look at other examples of artistic endeavor, whether its quilts, painting, poetry, cooking, gardening, or antique cars, try to identify what it is that makes one stand out against all the others.

Sometimes its the quality of the chiaroscuro (the play of light and dark); another time its just a few little touches of highly saturated color in a few key places. If you look at Dorothy Caldwells amazing quilts, youll see its often the apparently careless, beautifully carefree, or agonizingly nostalgic quality of a line of stitching. Designing on a Grid BY ELIZABETH BARTON I like using a grid as a background because it helps to anchor a piece. Ive noticed that it is not only quilters but many artists who love grids. Chuck Close often grids his work. Richard Diebenkorn transforms the local landscape into loose, irregular grids in his Ocean Park Series.

Bridget Riley organizes her shapes into vertical grids with diagonal lines. There are many more examples. If you start to collect grid ideas, youll soon have a nice little store of them that you can use when you need them. The number of quilters who have used a grid is vast. Take an hour or so to research all the different ways grids have been used, and then you can adapt many of these ideas for your own quilt designs. Grids also abound everywhere in our environmenta walk down the street will reveal at least half a dozen examples.

Next page

Sedna, by Elin Waterston While technical workmanship and skills are important in art quilting, a good grasp of design is equally important, as is a willingness to experiment with composition and materials. Art quilting is both art and quiltingboth aspects should be balanced, and yet the definitions of each should be stretched. We hope that this book will give you a foundation in the basics of good design, show you some techniques to use in your work, help you to develop a personal style, and show you what comes next in the process of becoming an art quilter. Take what you learn and make it your own.

Sedna, by Elin Waterston While technical workmanship and skills are important in art quilting, a good grasp of design is equally important, as is a willingness to experiment with composition and materials. Art quilting is both art and quiltingboth aspects should be balanced, and yet the definitions of each should be stretched. We hope that this book will give you a foundation in the basics of good design, show you some techniques to use in your work, help you to develop a personal style, and show you what comes next in the process of becoming an art quilter. Take what you learn and make it your own. Idea of a City, by Elizabeth Barton, 60 60

Idea of a City, by Elizabeth Barton, 60 60  From the Top, by Elizabeth Barton, 45 46

From the Top, by Elizabeth Barton, 45 46  Pump Court, by Elizabeth Barton, 35 48 Photos by Elizabeth Barton So think before you set out: What are you trying to convey? What is the experience that you want? Almost every other decision you will make about the piece will be informed by the main idea.

Pump Court, by Elizabeth Barton, 35 48 Photos by Elizabeth Barton So think before you set out: What are you trying to convey? What is the experience that you want? Almost every other decision you will make about the piece will be informed by the main idea.