First published 2011 in India

by Routledge

912 Tolstoy House, 1517 Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place,

New Delhi 110 001

Simultaneously published in the UK

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

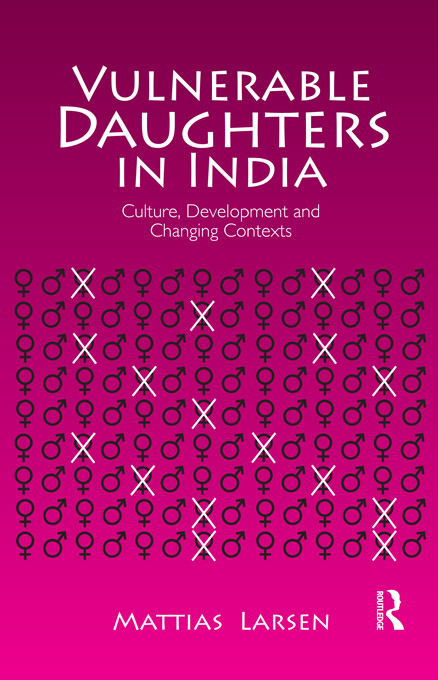

2011 Mattias Larsen

Typeset by

Star Compugraphics Private Limited

D156, Second Floor

Sector 7, Noida 201 301

Printed and bound in India by

Avantika Printers Private Limited

194/2, Ramesh Market, Garhi, East of Kailash

New Delhi 110 065

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-0-415-59751-7

This book is printed on ECF environment-friendly paper manufactured from unconventional and other raw materials sourced from sustainable and identified sources.

Preface

Believe it or not, people have understood the worth of girls, but this centuries old tradition is very hard to break. People are changing, but it will take time.

I n India, girls are aborted on a massive scale merely because they are girls. This fact is not only seriously disturbing but also perplexing on many levels. One of the most baffling aspects is described in the quotation above from one of the interviews; that this is the case in a time when people have started to appreciate the worth of girls in a way they did not before. These two aspects, the sheer magnitude of the problem and the contradictory nature of the developments surrounding it, are what compelled me to do the research for this book.

When I initially found out about the problem of missing girls in India, my first intuition was that the problem was related to the profound changes most parts of India are going through. It quickly became evident to me though that this potential relationship was surprisingly under-analysed. I have always found value in analysing problems as part of broader change processes. This is also the particular focus and strength of development studies, my main academic background. But as I gained more knowledge about the problem, particularly from fieldwork and discussions with people in the field, I realised that I had initially underestimated the importance of factors that in many ways seemed to represent the opposite of change. Certain ideas, beliefs and norms structure much of social life in a way that defines the role of sons and daughters in distinctly different guises. As work progressed, I struggled to comprehend how these two contradictory yet very central aspects of continuity and change fit together in the context of this problem. The chosen way of dealing with this by placing particular attention to changes in context is what gives the book its originality. It helps understand the dynamic nature of the problem, something that is reflected in the original results.

The fact that people I talked to continuously discussed both these sides as central to their understanding of the problem further complicated things for me. It was not until quite late in the process that my attention began to shift to the actual contradiction, and what it could mean in itself, that the biggest pieces of the puzzle slowly started to fall into place. I went through my material trying to see whether or not this actually was the case. It became increasingly clear that when people were describing what it is about their situation that makes them so apprehensive about having daughters I could see how they were actually relating it to the contradiction between these structuring features of ideas, beliefs, norms, cultural attributes and the many ways that peoples lives are changing at increasing speed in terms of different aspirations and opportunities that they are taking up.

During the years I spent working on this problem I heard many different reactions to this startling and disturbing fact. I often thought about why this might be so, but at some point I realised that these differences in reaction say something important about the nature of the problem. That what might explain a great deal in one context need not do so in another, and searching for general answers might not be the right way to go about it. Most people outside India tend to assume, probably as an initial way to fathom the moral issue of the problem, that this is done by people who do not really know what they are doing. Without judging people for this notion being based on a lack of knowledge of the actual circumstances as it is it really derives from the assumption that nobody will knowingly do such a thing. Assuming that it is done deliberately naturally carries a politically sensitive connotation that many people seem unwilling to believe. Another very common response by non-Indian observers is to assume that Indian women are passive victims who are forced by their husbands or by other men in their surrounding to submit to this.

As expected, Indian observers react very differently. First of all, since it is a problem of such an enormous extent it is discussed and debated regularly in the media and on what sometimes seems to be every street corner in the country. This means that a lot of people have strong opinions on the subject. One of the most common reactions is that the availability of the techniques to carry through sex-selective abortions provided by unscrupulous medical practitioners hoping to get rich is the reason why the situation is the way it is. Indeed, the extent to which these techniques are available is mind-boggling. I can honestly say that of all the people I have met during field-work and time spent in India, I cannot remember ever having met anyone who either did not know where it could be done or how to find out where to do it. Another very common reaction, which is very easy to relate to, is that it is difficult to accept that there is an important cultural aspect involved.