From genesis to birth, the journey of any book is filled with many a twist and turn along the way. Scrutinising the lives of Irish geniuses has ensured countless exciting moments on this books passage, and for this we greatly appreciate the contributions of a number of people. First and foremost we would like to thank Sen OKeeffe and Peter OConnell of Liberties Press, without whose vision, professionalism and diligence this book would not have seen the light of day. For discussions, insights and support of diverse kinds we are grateful to Pat Matthews (President of the World Autism Association), Viktoria Lyons, Michael Gill, Brendan OBrien, Maria Lawlor, Jerry Harper, Ioan James, John Richmond, Bill Tormey, Emmet and Elisabeth Arrigan, Theresa Scott, Anna Coonan, Patricia Maloney, Ellen Cranley and Aoife OConnor. For sharing her ideas and aspirations in the foreword of this book we are also grateful to Kathy Sinnott MEP.. A special word of thanks and appreciation is extended to the many parents of children with autism, as well as persons with autism/Aspergers syndrome, who continue to educate us over the years. For their unfailing help we thank the librarians at Trinity College Dublin, in particular Virginia McLoughlin, Joe OBrien, Philomena Nicholson and Joseph McCarthy; at the Royal College of Surgeons, in particular Joan Moore; and at Dublin City Library and Archive Collections. Finally, Antoinette would like to thank her parents, Michael and Anne, and family and friends, while Michael would like to thank his wife Frances and sons Owen, Mark and Robert, for their support and forbearance in the writing of this book.

We were reminded in a recent disABILITY campaign to focus on a persons ability, not his or her disability. This reminds us of the obvious fact that, for example, even though a man cannot walk, he may be able to read, write and talk. It also attempts to make us aware that a woman who has a visual impairment can not just hear but may hear better than a sighted person.

But there is a deeper meaning. Ability is not necessarily just what the person can do, apart from what he or she cannot do and apart from any compensating skills. For some people, the ability is the disability itself.

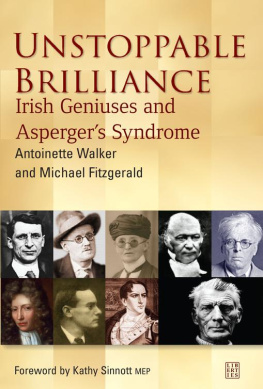

In Unstoppable Brilliance: Irish Geniuses and Aspergers Syndrome by Antoinette Walker and Michael Fitzgerald, we have the stories of gifted men and women whose ability and disability was Aspergers syndrome. They were gifted with the aspergic ability to, on the one hand, give themselves completely to the pursuit of their interests, and on the other to bypass the distractions and obstacles of life, not as hurdles to be jumped, but as irrelevancies to be ignored or not even noticed. They were men and a woman who were able to trail-blaze to the frontiers and to penetrate the centre, laying bare the heart of maths and science, Aboriginal and modern man, language and politics.

This is the uniqueness of their abled achievement. Many bright people travel the same paths but get sidetracked along the way. Consequently, when these geniuses with Aspergers syndrome arrived at their destination, they found it a solitary place. But here too the aspergic ability equipped these geniuses for survival in isolation and more productivity.

We who have benefited from their ability should be grateful because Aspergers syndrome, though an ability, is also a disability with a burden of pain. Their legacy, which we now enjoy, was achieved at a price of loneliness and social, emotional and physical struggle both for the person and those that loved them.

Many people in Ireland today have Aspergers syndrome. Not all are geniuse but, in my experience, all are gifted and have special areas of talent. It is my hope that the stories in this book will force us to ask ourselves some important questions. Why are children with Aspergers often diagnosed so late in Ireland? And why, when that diagnosis finally comes, does it seem to close instead of open doors. Why, given the very individual needs of people with Aspergers, are there so few specialised services to meet those needs? Where are the information and training services for teachers, parents and employers? What does our high-pressure exam-based education system do to the student with Aspergers? Why is there little outreach to young adults with Aspergers to help them establish themselves in work and in the community. Where is a policy of understanding support for a family of a child or a parent with Aspergers? Why are so many people with Aspergers misdiagnosed as having a mental illness? And why are so many of these misdiagnosed people medicated to the point of developing a mental illness?

Finally, why are Aspergers and other autistic spectrum disorders still seen as psychiatric or psychological conditions, with no recognition of the medical problems that cause them? It is no coincidence that most of the people in this book suffered poor health, especially gastrointestinal disease, poor immune protection and eye problems. Why, despite years of campaigning, is there still no medical treatment for autistic spectrum disorders in Ireland? And are we cherishing people with Aspergers syndrome, and their gifts?

It is my fervent hope that celebrating great Irish people who had Aspergers will somehow give all of us a greater awareness of the people in our midst who share this ability/disability. I hope too that Unstoppable Brilliance will inspire the political descendants of de Valera, Emmet and Pearse to take seriously both the potential and the plight of all people with Aspergers in Ireland today.

Kathy Sinnott MEP , March 2006

There is something about genius that intrigues. Being in the presence of someone with exceptional talents and abilities is no ordinary event and the memory of it can stay with us long afterwards. Because nature throws up geniuses only very rarely, we are aware of just how exotic a species they are. We do not expect them to be normal and take for granted their enigmatic, odd and bizarre ways. They can also sometimes inspire ridicule and fear and may not always be likeable figures. Richard Ellmann, the celebrated biographer of James Joyce, believed that the Irish are gifted with more eccentricities than Americans and Englishman. To be average in Ireland, he felt, is to be eccentric. Perhaps Ellmann was a little biased; nonetheless, the nine characters in this book all of them Irish showed remarkable abilities and were strange and complex individuals indeed.

Is there a biological basis to genius? It is the contention of this book that there is. The Latin origins and derivations of the word would suggest so: genus, meaning family, ingenium, a natural disposition or innate capacity, and gignere, to beget. Recognising that eccentricity is part and parcel of genius, many, such as theatre and opera director Jonathan Miller, would argue that geniuses have normal psychological disabilities rather than some mere disorder. This book attempts to put a name on those normal psychological disabilities with a diagnosis of Aspergers syndrome, an autistic spectrum disorder. In essence, it is a forensic look at the trappings of genius.

All geniuses possess a unique kind of intelligence. The paediatrician Hans Asperger observed that highly original thought and experience was found in some autistic children and believed that this could lead to exceptional achievements later in life. He wrote about autistic intelligence a kind of intelligence untouched by tradition and culture. According to the neurologist Oliver Sacks in his book An Anthropologist on Mars, this form of intelligence is unconventional, unorthodox, strangely pure and original and related to the intelligence of pure creativity. Certainly, the characters discussed in this book, regardless of their chosen field, possessed this kind of intelligence: primitive and pure, intuitive and instinctive, and marked by a moral intensity. All of these characters were willing to take intellectual risks by combining what may have looked like unrelated ideas to produce something radically new.