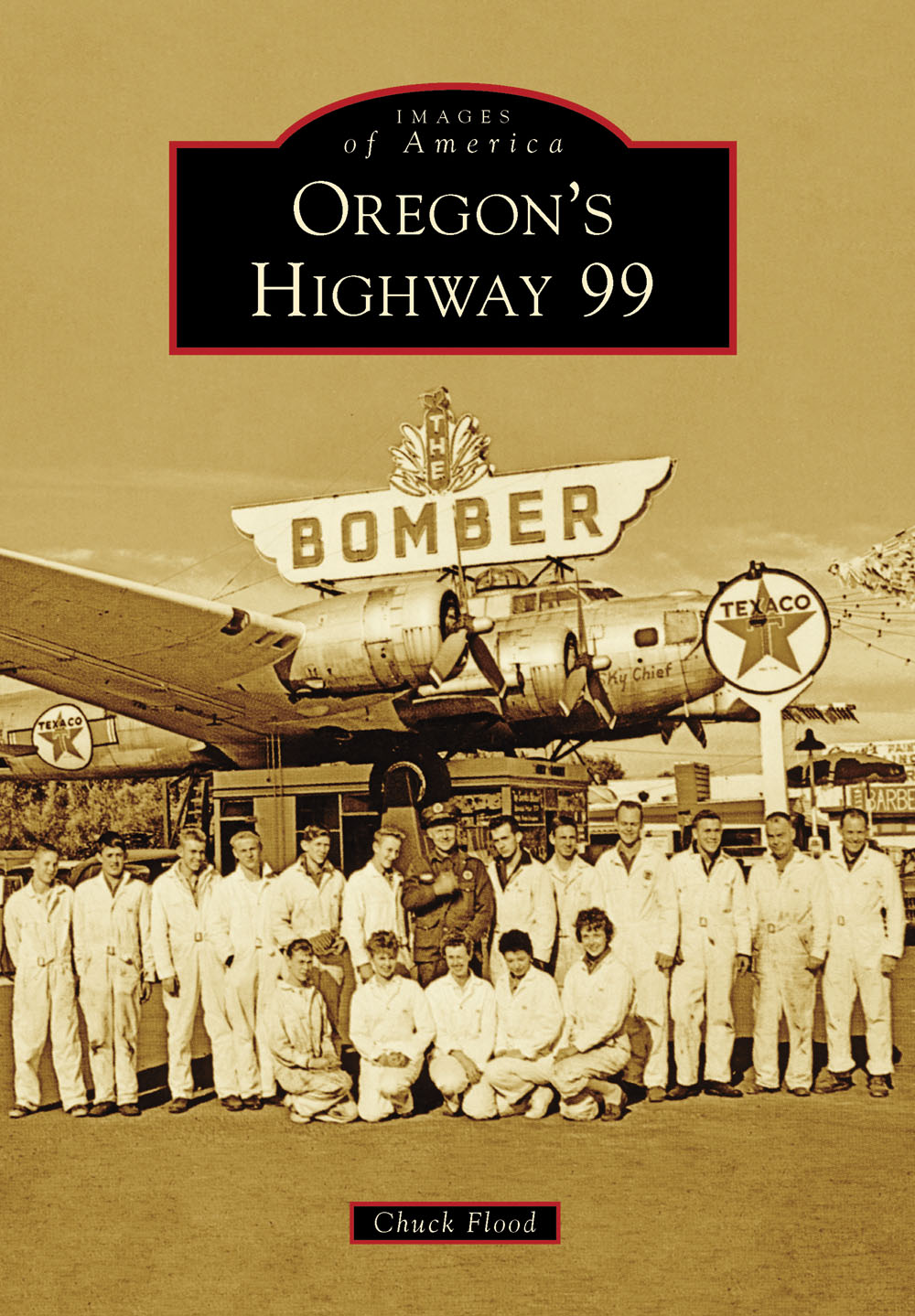

IMAGES

of America

OREGONS

HIGHWAY 99

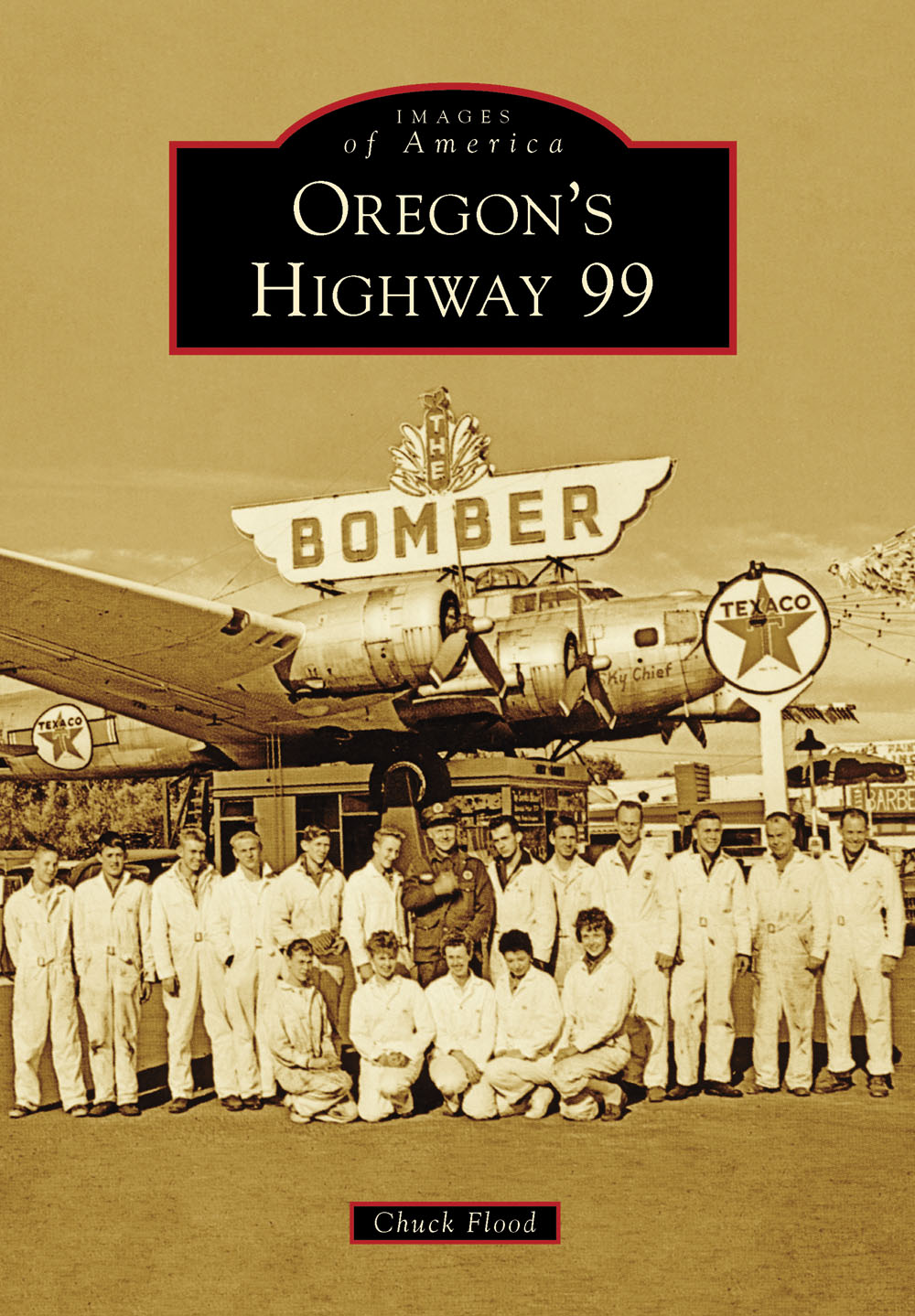

ON THE COVER: Art Lacey stands in front of The Bomber south of Milwaukie. Lacey purchased a surplus B-17 bomber in 1947 and flew it to Troutdale. He loaded it onto four trucks and moved it to its new home atop his service station on McLoughlin Boulevard. The Bomber was probably the best-known roadside attraction along Oregons Highway 99. Lacey is in the dark uniform; the others are not identified. (Jack ODonnell Collection.)

IMAGES

of America

OREGONS

HIGHWAY 99

Chuck Flood

Copyright 2016 by Chuck Flood

ISBN 978-1-4671-1534-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439656549

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015948920

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Debbie (of course), Mike and Jennifer for putting me up, and Jack ODonnell for his continued support.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks are due to the individuals and organizations that offered their support and assistance with this project:

Addie Maguire, Albany Regional Museum, Albany (ARM)

Mary Gallagher, Benton County Museum, Philomath (BCM)

Devin Busby, City of Portland Archives, Portland (CPA)

Karin Morey, Clackamas County Historical Society, Oregon City (CCHS)

Jack ODonnell Collection (JCOD)

Linda VanOrden, Junction City Historical Society, Junction City (JuncCityHS)

Joan Momsen, Josephine County Historical Society, Grants Pass (JoCoHS)

Cheryl Roffe, Lane County Historical Museum, Eugene (LCHM)

Chris Peterson, Oregon Digital, Corvallis (OD-OSU)

Oregon Historic Photograph Collections (OHPC)

Austin Schulz, Oregon State Archives, Salem (OSA)

Diana Painter, Oregon State Historic Preservation Office, Salem (OSHPO)

Dave Hegeman, Oregon State Library, Salem (OSL)

Original Pancake House Archives, Portland (OPH)

Patty Chap and Bette Jo Lawson, Polk County Historical Society, Rickreall (PCHS)

Jim Roake, Roakes the Hot Dog Folks (JR)

Pat Harper, Southern Oregon Historical Society, Medford (SOHS)

Sean Garvey, Tigard Public Library, Tigard (TPL)

Karen Lange, Washington County Museum, Portland (WCM)

Kylie Pine, Willamette Heritage Center, Salem (WHC)

Images with credit lines are courtesy of the organization or individual whose abbreviation appears in the above list, which should be used to determine the contributors full name. Images without credit lines are from the authors personal collection.

INTRODUCTION

Highway 99 entered Oregon by crossing the Columbia River north of Portland and exited the state via the Siskiyou Mountains south of Ashland. That can be stated with certainty. Between those two fixed points, however, Highway 99 and its predecessor, the Pacific Highway, followed various and sometimes bewildering routes as it traversed 250 miles of fertile fields and forested hills. It was not until the 1930s that Highway 99s official alignmentincluding its major branches, 99E and 99Wwas finalized. Today, almost all of the old highway still exists and is in daily use.

Like its neighbor states Washington and California, Oregon is bifurcated by the Cascade Mountains into a wet west side and a dry east side. In broad terms, agriculture, forest products, and the states largest cities characterize the west side; the dry eastern side is more typified by mining, ranching, and wide open spaces. Both sides were well populated when Lewis and Clark made their famous trek to the Pacific Ocean.

Early post-contact overland travel into Oregon was from the east. The mighty Columbia River was a waterway for fur traders and explorers; starting in the 1840s, the Oregon Trail swarmed with emigrants on a one-way search for a new life. They reached their destination in the broad, level Willamette Valley. Within a decade, a sizeable population of settlers had grown up in the valley. Towns quickly followed; trading points for agricultural products, the earliest were usually along rivers, but inland settlements soon appeared.

Though home-seekers from the east continued to pour in, by the 1850s, north-south travel routes had developed in western Oregon. The Applegate Trail, an alternate route of the Oregon Trail that delivered settlers into the state via California, became a main thoroughfare for Oregon miners bound for the mother lode of gold discoveries in the foothills outside Sacramento. By 1859, several territorial roads had been established along the edges of the Willamette Valley, and towns became connected through a network of farm-to-market roads.

As population grew, so did commerce. Stagecoaches and freight wagons began operations, but few of the early roads were intended for long-distance journeys. Railroads handled that kind of traffic. By the mid-1870s, the locomotives of the Oregon & California Railroad were steaming up and down the Willamette Valley. As the 20th century dawned, road conditions were still primitive throughout most of Oregon.

Then came the automobile. Originally a plaything of the rich, autos rapidly became popular, safer, and affordable. In 1900, only 8,000 automobiles were registered in the entire country; by 1930, the nations roads bulged with more than 23 million cars and an additional 3.5 million trucks. Commercial travel increased exponentially. Suburbs developed as workers realized they could live at a distance from their workplaces. Tourism was born. People traveled for the sheer fun of it, for the excitement of seeing sights and places theyd heard of but never dreamed theyd be able to visit.

It didnt take long to realize that existing roads were inadequate for the demand. Many early highways were no better than the wagon roads that preceded them; dust-choked in summer and mud-pits in the rainy season, they often got from point A to point B via points C, D, X, and Y. Good roads became a rallying cry among motorists. Major highway-building programs resulted from demands for getting from place to place faster and more directly.

In 1913, the Oregon legislature created a state highway commission with the power to raise funds for highway construction. Among its first projects was the Pacific Highway, proposed to run from Portland to Salem through Oregon City; then through Albany to Eugene, Cottage Grove, Roseburg, Grants Pass, Medford, and Ashland.

Planning had hardly begun before an effort was made to split the route into an East Side and a West Side Pacific Highway (not to be confused with Highways 99E and 99W, which came later). The East Side Pacific Highway won the contest for primacy and in 1927 was designated US Highway 99 as part of a national initiative to replace highway names with numbers.

For the first years of its life after being decreed into existence, the Pacific Highway simply followed the routes of preexisting roads. Beginning in the 1920s, improvements in the form of realignments, bypasses, paving, and new construction began to transform the patchwork of old roads into a unified highway. These improvements continued periodically and are still ongoing today.

The West Side Pacific Highway finally achieved national highway status in 1937 when it was redesignated Highway 99W. At the same time, the East Side Pacific Highway became Highway 99E. As they had since early days, the 99E and W came together at Junction City to form Highway 99 and continue on to California.

Next page