Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Peg Willis

All rights reserved

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.755.3

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.271.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To the memory of Clarence Mershonlifelong resident of east Multnomah County, who wrote down the stories, lest we forgetand the Friends of the Historic Columbia River Highway, whose valiant efforts have worked miracles in preserving and reconnecting the fragments of this hidden beauty.

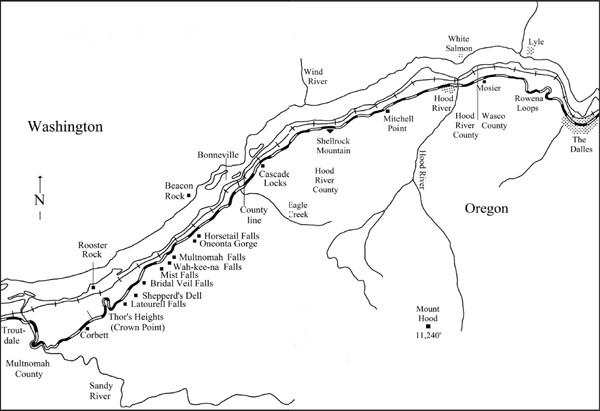

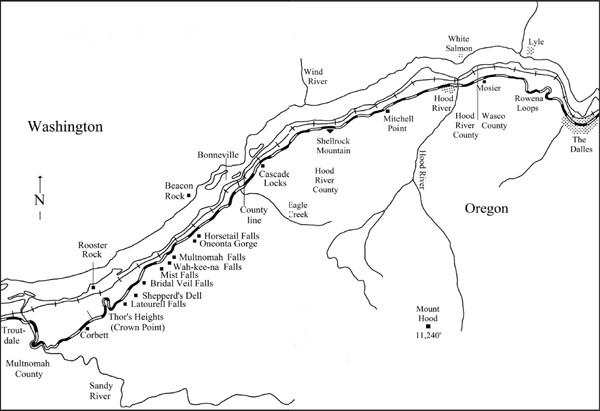

The Historic Columbia River Highway from Troutdale to The Dalles. Map by the author.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

A book can never be the work of one personespecially a book such as this, which requires the assembling of many details from many sources, selected from the overwhelming abundance of information available. I would especially like to acknowledge Jeanette Kloos and David Sell. Jeanette is the former scenic area coordinator for the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) and founder and president of the Friends of the Historic Columbia River Highway. David is the retired project manager with the Federal Highway Administration. Both these people have been more than generous with their many period photographs of the highway and its construction and have given generously of their time and expertise to supply answers to my questions and offer correction when I got something wrong.

Thanks also to Ellnora Lancaster Rose Young, Samuel Lancasters great-granddaughter; Marion Ackerman Beals, daughter of Frank Ackerman, marble carver; Benny DiBenedetto, son of Gioacchino DiBenedetto, stonemason; Laura Wilt at the Oregon Department of Transportation library; Bob Hadlow, ODOT Historian, and other ODOT employees who have answered my many questions; Dave Olcott, Steve Lehl and the many other wonderful people Ive met while volunteering at Vista House who have helped me fill in the story; and the many museums and historical societies that have aided my search for photos and information

Any mistakes in this book are wholly my own.

While starting with the nuts and bolts of the highways history, for those unfamiliar with it, I have also tried to fill in the story with some of the lesser known details for the sake of those who already know and love the highway story and want to know more.

A few pronunciations:

Celilo: s LY lo

LY lo

The Dalles: the DALZ

Lancaster: LAN ks ter

Multnomah: mult NO m

Oneonta: oh nee AHN t

Oregon: OR ee gun (three syllables, not two)

Pittock: PIT  k

k

Spokane: spo KAN

Thor: Tor (Norwegian)

Umatilla: YOU m TIL

TIL

Wemme: WEM ee

Willamette: w LAM

LAM  t

t

Yeon: yawn

The schwa ( ) is the vowel sound in the first syllable of the word again.

) is the vowel sound in the first syllable of the word again.

INTRODUCTION

THE GORGE OF THE COLUMBIA

The Columbia River is long, large, beautiful and wild. At least, it was wild in its earlier livesof which there were several.

On its journey of 1,243 miles, it drains a total area of 259,000 square milesroughly the size of Francefrom British Columbia in Canada and seven U.S. states. It serves as the border between Oregon and Washington for 300 miles and discharges 17.5 trillion gallons of water into the Pacific Ocean each year.

Several men in the history of the Pacific Northwestmen who were by nature curious and imaginativesuggested that the Columbia River watershed had been visited at sometime in the past by a massive catastrophe involving water. During the mid-1800s, Irish-born Thomas Condon (18221907) served as a Congregational pastor to churches in several Northwest townsamong them, The Dalles, Oregon. During his time in The Dalles, he was able to do considerable exploring in eastern Oregon and became fascinated with the landforms and fossil beds in this geologically rich area. He was especially intrigued by the presence of fossilized seashells in this arid, near-desert land.

In the next generation, Samuel Lancaster (18651941), designer of the Columbia River Highway, wondered whether the Columbia River Gorge had been formed by a wall of water. His suggestion came both from his knowledge of Condons explorations and research and also from personal experience in the Gorge.

J. Harlan Bretz (18821981) is given credit for first speculating, and then insisting, that the scablands of eastern Washington were carved by a flood of biblical proportions. He noted the bathtub ring effect on the hills and felt that these massive horizontal markings could only have been produced by water washing back and forth at that level for an extended period of time. He pointed out the dry waterfalls, hanging valleys, potholes, channeled scablands, massive gravel deposits and erratics (isolated rocks from a foreign origin) scattered throughout the Columbia and Willamette River Valleys as further proof of his theory. And where would this unthinkably immense volume of water have come from? Some place north, Bretz speculated, and he referred to this as-yet-undiscovered source as the Spokane Flood.

Bretz was ridiculed for his ideas. Invited in 1927 to present his findings on The Channeled Scablands and the Spokane Flood at the Geological Society of Washington, D.C., Bretz attended in good faith but found that the event might better have been described as an ambush. He presented his information; then, one by one, his peers tore apart his beliefs. These learned men based their objections on academic knowledge rather than actual field experience in the scablands of eastern Washington. To be sure, this is the purpose of such conferencesto consider possibilities and then try to disprove them. Those ideas that cannot be disproved must be considered as possibly viable truths. But feelings were strong in opposition to Bretzs claimsvery strong.

This was at a time when James Huttons theory of uniformitarianism was holding sway. Huttons theory that the present is the key to the past put forth the idea that outside the occasional localized earthquake, flood or volcanic eruption, the earth continued as it had in the past and would, therefore, have taken eons to evolve to its present design. Not only that, but this extended time frame was necessary to fit in with Darwins theory of evolution, which was gaining wider and wider support. And of course, there was no allowance for a flood anywhere near the size needed for Bretzs theory.

Next page

LY lo

LY lo