ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to extend my gratitude to all those people and organizations who responded to my phone calls, visits, and e-mails. I thank them for their support of this project and their willingness to share their photographs, memories, and family stories.

I would also like to offer my sincerest thanks to Elizabeth Isles, director of the Dublin Heritage Center. Without her help, guidance, and support, I could have never finished this book. She was indispensable in granting me unfettered access to every record at her disposal. Thank you, Elizabeth, for giving me this tremendous opportunity and entrusting to me so great a treasure. All photographs in this book without a credit line are courtesy of the Dublin Heritage Center.

To Mary Chervet at Pleasantons Museum on Main Street, thank you. She opened the doors of the museum to me and allowed me direct access to their superb photographic collection. Many of the pictures in this book are here because of her.

I would also like to thank my neighbor and friend Mike Brogdon. His willingness to let me scan numerous batches of photographs and historic documents made such a monumental task far easier than it would have been otherwise.

For those who have come before me, I realize that much of what is contained within these pages would not exist without their years of research and diligencepeople like Virginia Bennett Smith, Dick Finn, Anne Homan, and John and Marie Cronin. In a time when few people cared about preserving the past, they rescued many of the treasures we enjoy today. As a philosopher once said, I can see a little farther because I stand on their shoulders.

To my wife, Kathleen, and my children, Bethany and Nathan, thank you for giving me the time needed to research and write this book. If it wasnt for your support and encouragement, I could never have been able to finish this project. Gratitude is a word that is not strong enough, but it will have to suffice.

SOURCES

Dougherty family collection

Dublin Heritage Center

Fallon family collection

Green family collection

Hansen family collection

Harvey family collection

Kolb family collection

Koopmann family collection

Martin family collection

Moller family collection

Murray family collection

Museum on Main Street, Pleasanton

Nielsen family collection

Reimers family collection

Terra family collection

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

TAMING THE WILDERNESS PREHISTORY1850

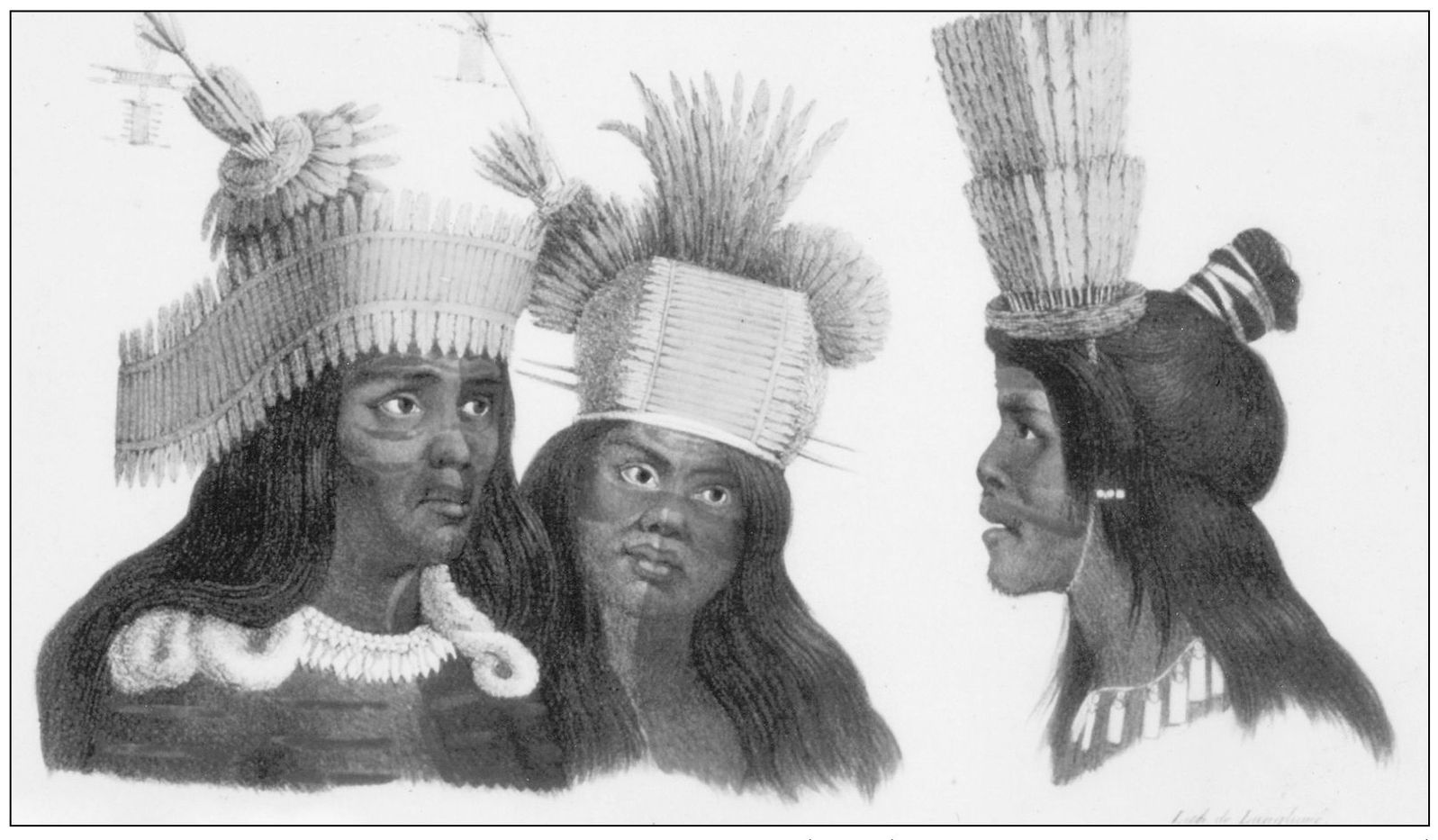

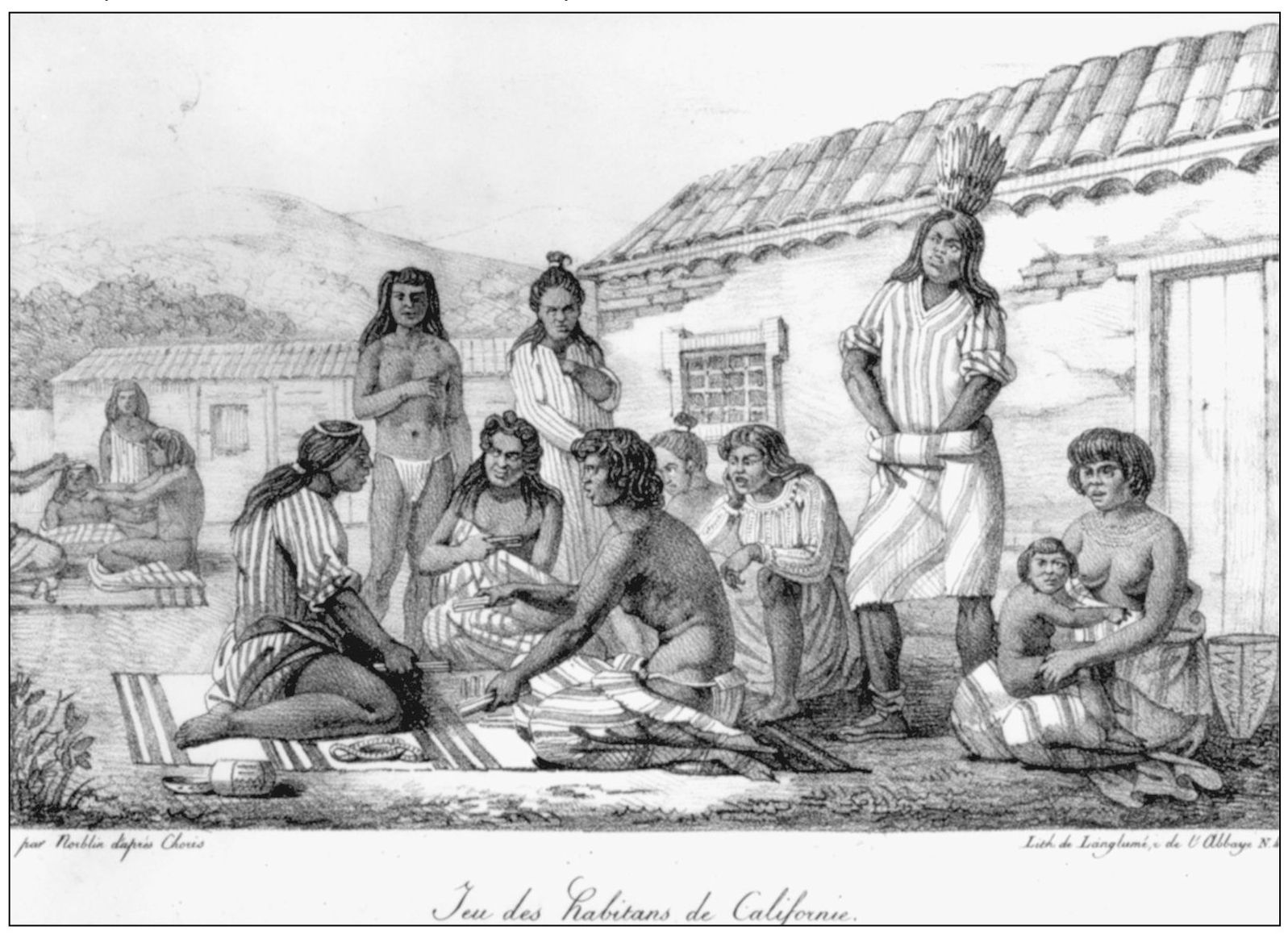

OHLONE INDIANS IN HEADDRESS. It is uncertain when the first Native Americans appeared in the greater Bay Area, but radiocarbon dating suggests as early as 5,000 years ago. Unlike other Native American tribes throughout the United States, the Ohlones lived in small family groups or in villages. There is also evidence they practiced horticulture, hunted local game, and developed complex social structures. The first Spaniards to see the Amador Valley were with the Fages Expedition in 1772. Fages and his men entered the valley as they were returning from an expedition to find a route to Drakes Bay. The party watered their horses at well-known watering holes, one of which was probably Alamilla Springs in Dublin. With the coming of the missions, specifically Mission San Jose in 1797, the Spaniards established the chief trading center and administrative outpost for the area.

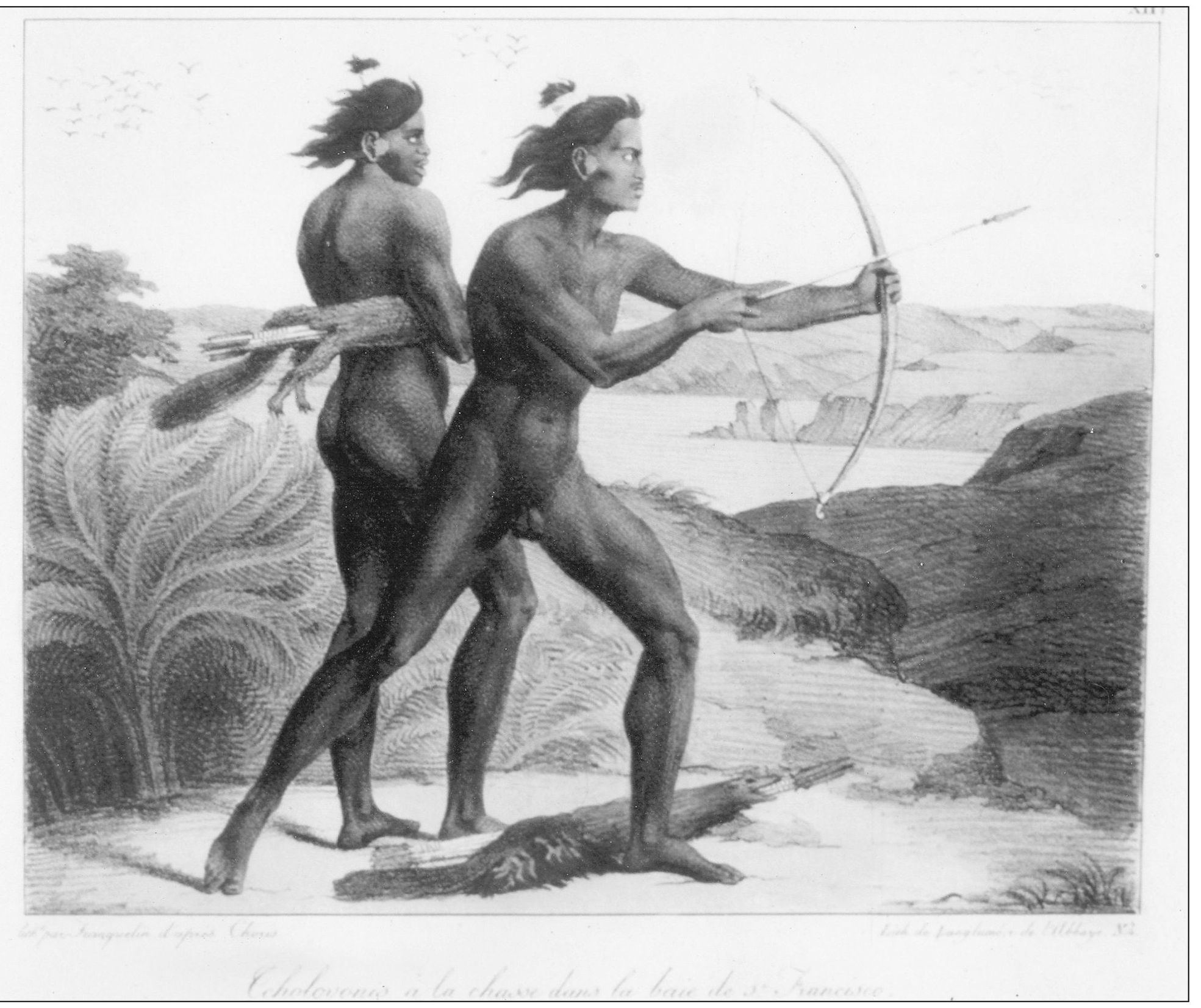

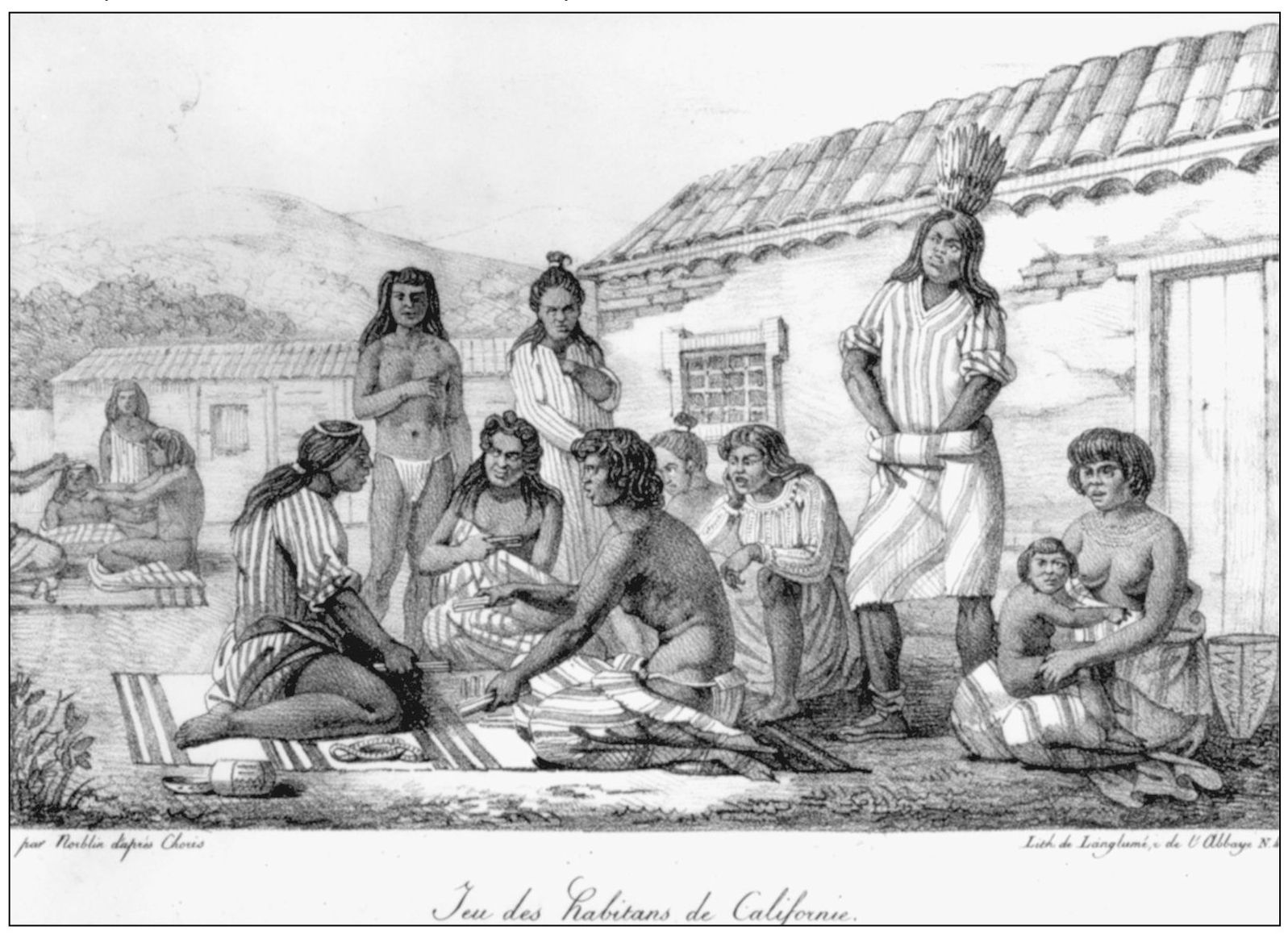

OHLONE INDIANS WHILE HUNTING. Spanish fathers viewed the California Native Americans as lost children, incapable of understanding beyond a simple level. Further, they saw them as lost souls, doomed to eternal suffering unless converted and baptized. The priests were appalled to see nearly naked Native Americans, smeared with mud to keep out the cold, living on acorn mush in huts made of reeds. Their plan was to clothe the Native Americans and teach them to weave cloth, to improve their diet, and to raise beans, corn, and fruit. They also taught them the importance of building permanent houses with adobe bricks. This plan would take about 10 years, the padres calculated, and then the Christianized Native Americans would settle their families on small farms, effectively colonizing California.

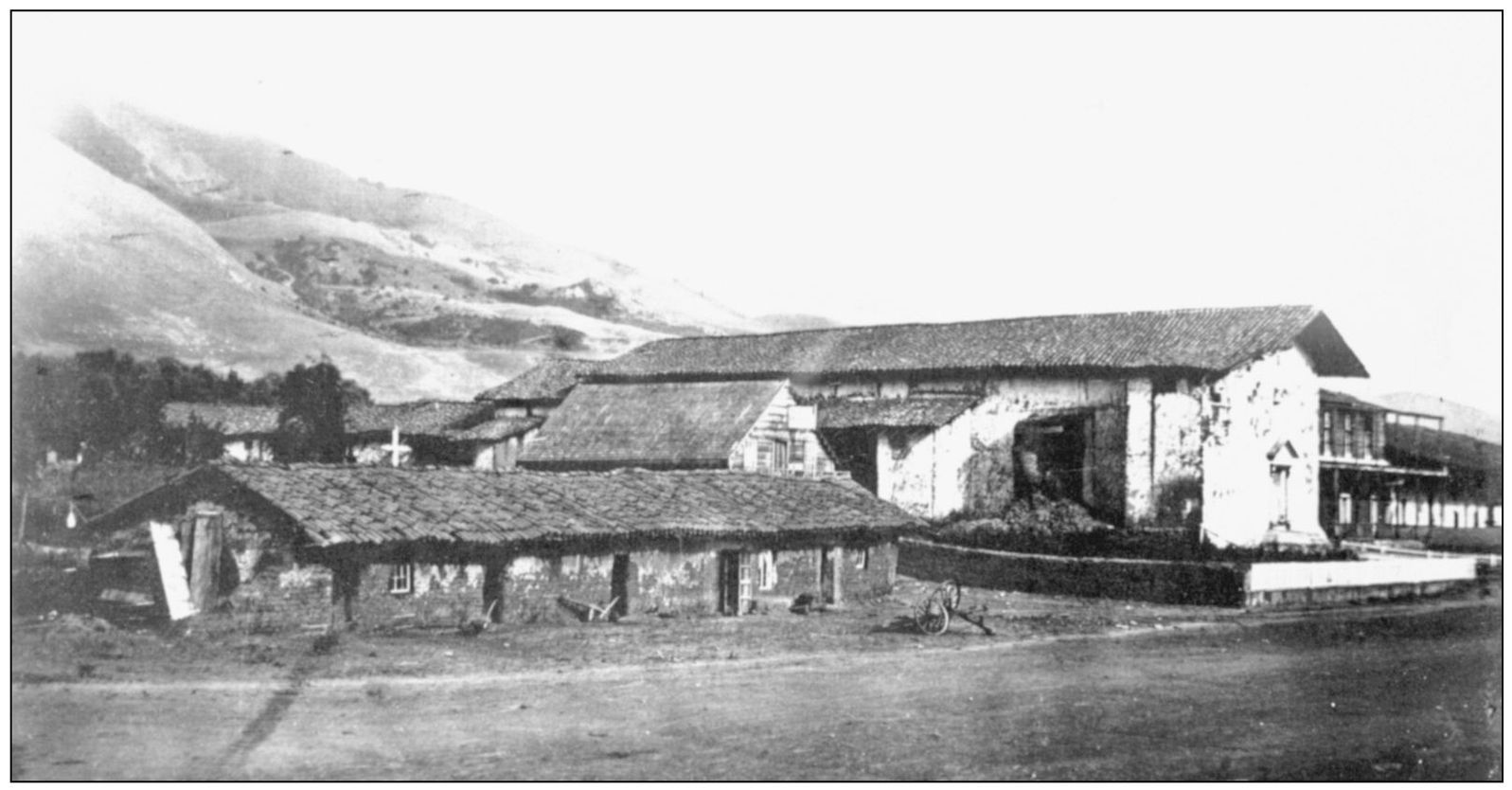

MISSION SAN JOSE DAGUERREOTYPE TAKEN IN 1852. Fr. Fermin Lasuen founded Mission San Jose on June 11, 1797. With the establishment of a permanent Spanish settlement, life for the Ohlones would never be the same. Hundreds of Native Americans came to live and work at the mission, which became the center of their religious, education, social, and economic lives. They erected adobe buildings, and they learned to make clothes, shoes, tools, and ropes. Mission San Jose baptized more Native Americans than any other mission, having their population peak around 1,900. Over the next two decades, the mission system faced a gradual period of decline. By 1834, the Spanish missions became secularized. In 1868, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake along the Hayward Fault struck the area, destroying most of the church.

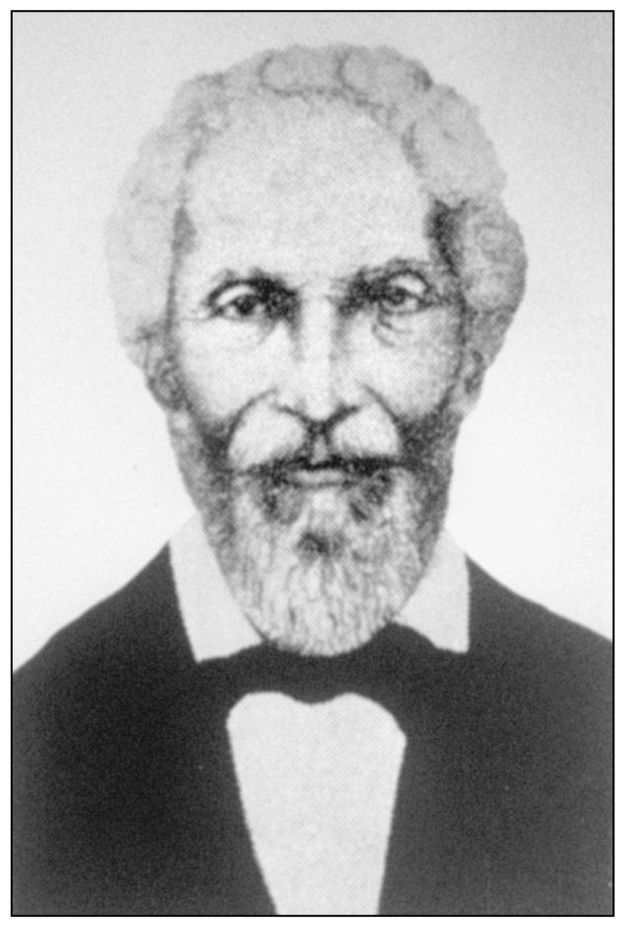

JOSE MARIA AMADOR (17811883). The secularization of California missions from 1834 to 1837 opened great amounts of land throughout California for grants. One of those to whom land was given was Jose Maria Amador. Born in San Francisco in 1781, he served as a private in the Spanish army from 1810 to 1827. After his discharge, he became the mayordomo at Mission San Jose, holding the post until 1835. His years of service as a soldier and administrator merited him a grant of four leagues (a league being 4,400 acres) of mission land in 1835. He called it Rancho San Ramon. As the years passed, Amador eventually sold off all of his vast holdings and died in 1883 in relative poverty at Watsonville. He is buried in Gilroy.

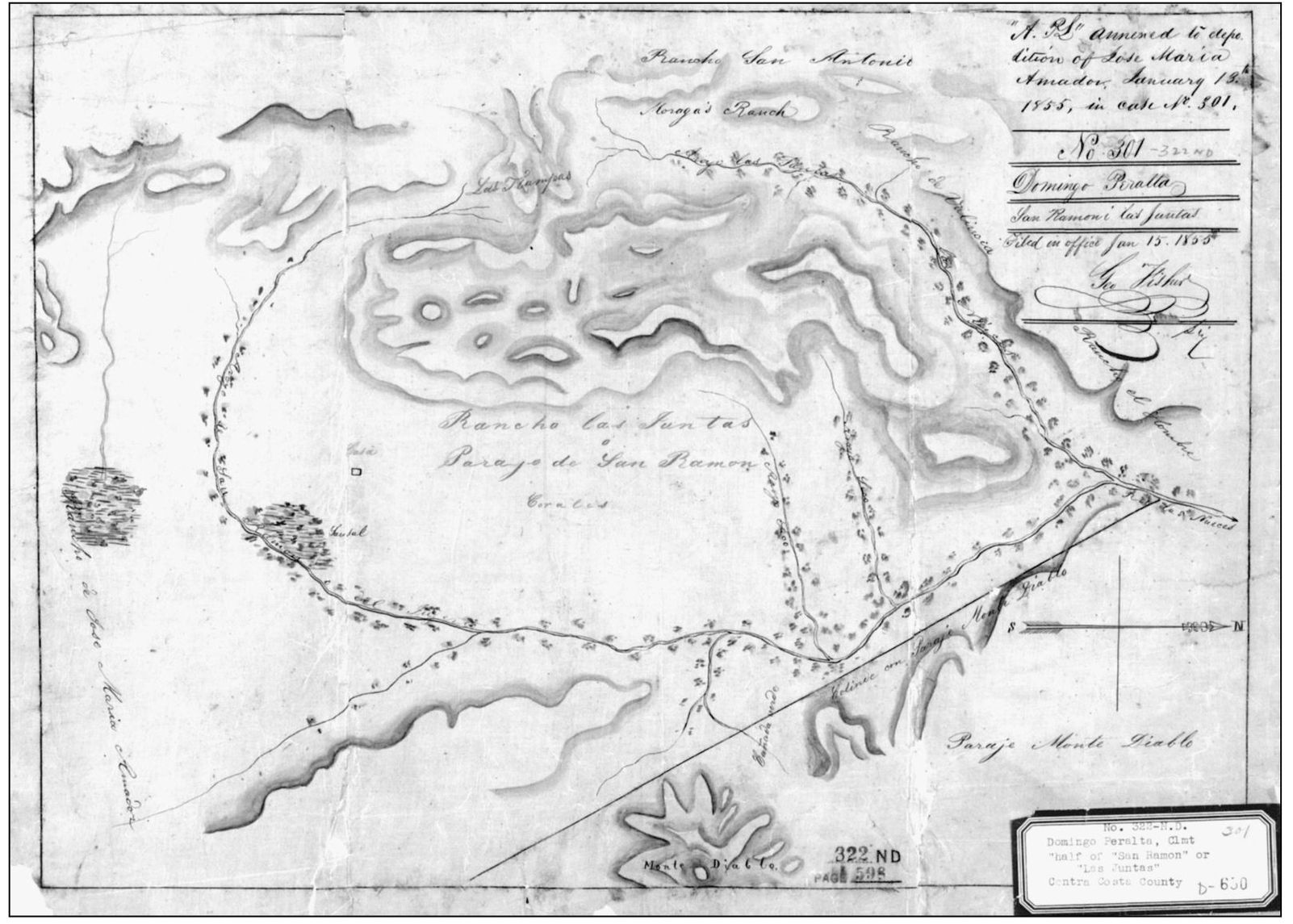

AMADOR PROPERTY MAP, 1855. This sketch of Jose Maria Amadors property in 1855 shows just how varied and diverse the land was at that time. Topographical markers, such as hills, summits, rivers, and trees, typically served as boundaries for early Spanish and Mexican land grants. With the coming of immigrants and Americans to the gold fields of the Sierra Nevada, Jose Maria Amador sold portions of his property in what is modern-day Alameda County. By 1855, as the map indicates, his property holdings had been reduced significantly, lying just north of the Contra Costa County line. (Courtesy Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.)