Anyone can learn to navigate on large bodies of water. The theory is not very complicated, in principle, the use of a compass, chart and simple tools such as pencil, eraser, dividers and ruler are sufficient. In inshore areas and at sea, a tidal atlas and tide timetable are also required. However, it is advisable to master a number of skills. To reach a destination, a navigator must know the meaning of lines, symbols and abbreviations on a chart, be able to take compass errors into account and be able to understand the effects of wind and currents. Although, strictly speaking, it is not necessary to sail from A to B, the use of electronic aids is extremely useful and, for the modern navigator, indispensable.

Satellite navigation and plotters, PCs or tablets with electronic charts offer convenience, increase insight and thus to a large extent safety for ships and their crew. In addition to the theory in this Navigation for Beginners book, many tips therefore also refer to the use of GPS satellite navigation (Global Positioning System) and applications for on-board PCs and tablets so that advanced users can also refer to this.

The basic tools for navigation: pencil, compass and ruler

Nautical Charts

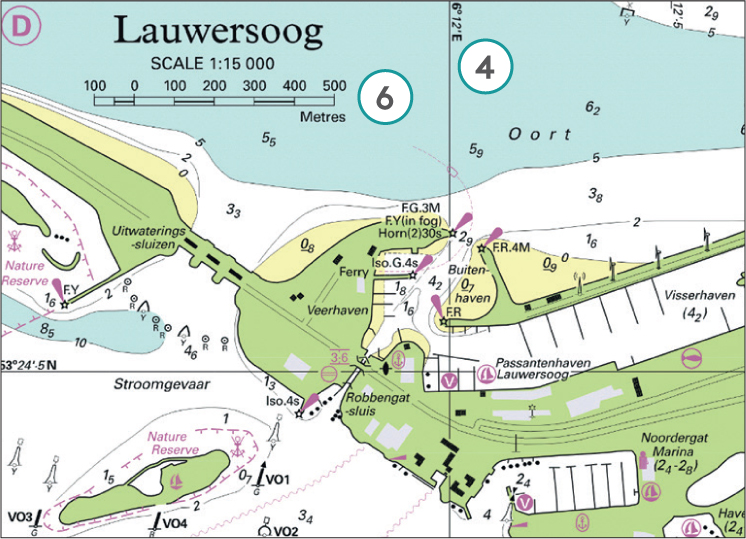

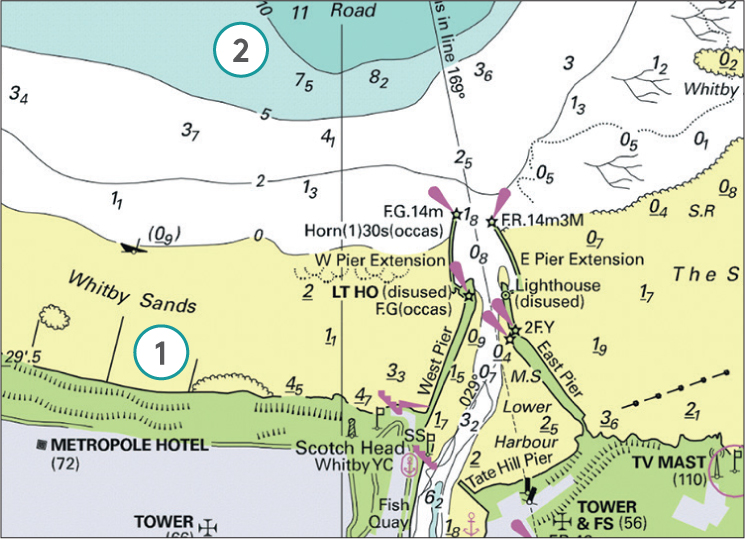

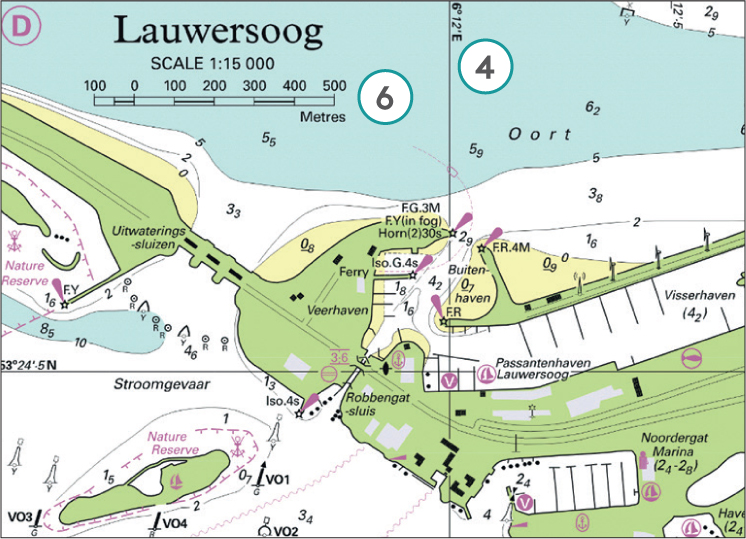

Paper charts come in many shapes and sizes. Hydrographic Offices around the world produce them primarily for use by ship owners, navies, and other professional users. The data also serve as a basis for chart material specifically intended for pleasure craft. Regardless of the type of chart, the following data will always be present:

Coastlines

Water depths and depth lines

Landmarks and dangers

A grid of latitude and longitude

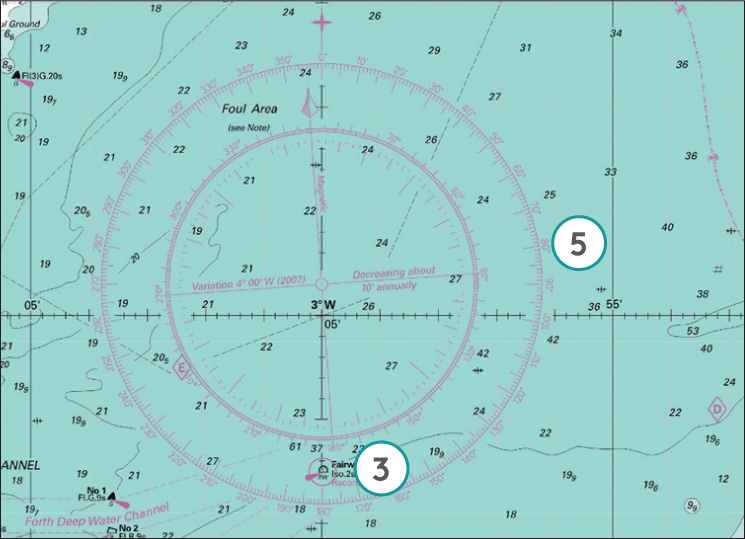

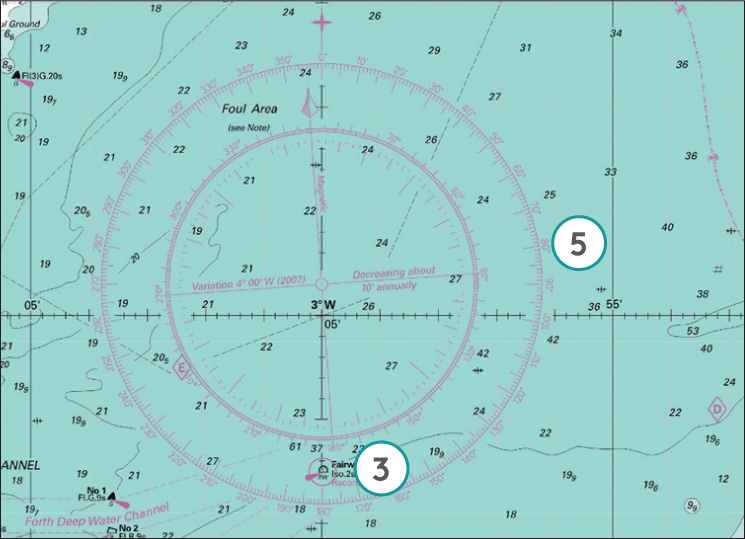

At least one compass rose, usually several

Chart scale, projection method and geodetic datum

British Crown Copyright

Position, latitude and longitude

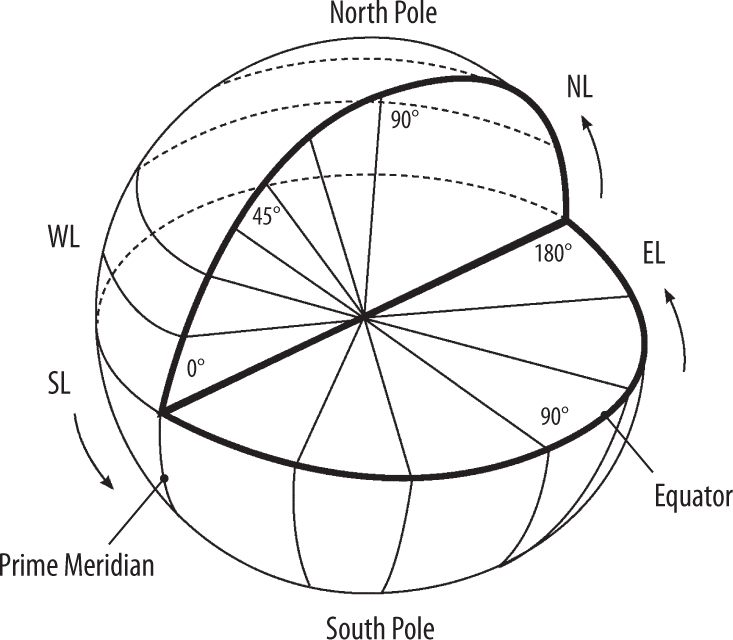

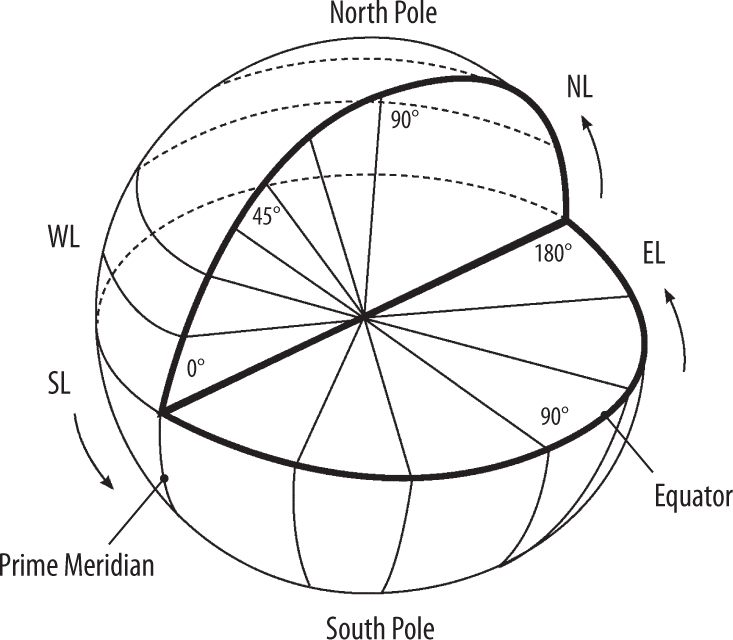

The grid of latitudes and longitudes on a nautical chart is necessary for determining location and distance. Thanks to this system of co-ordinates, any place on Earth can be represented as a geographical position. To achieve this, the Earth is covered with a network of imaginary lines: parallels and meridians. The most important and largest (zero) parallel is the equator and the most important (zero) meridian runs through Greenwich according to international agreements.

Latitude is the distance north or south of the equator. The North Pole = 90 north latitude (NL), and the South Pole = 90 south latitude (SL). Longitude is the distance east or west of the Prime Meridian (Greenwich). 180 west = 180 west longitude (WL) and 180 east = 180 east longitude (EL). All meridians (lines of longitude) are the same length but the distance between them decreases towards the North and South Poles. Parallels (lines of latitude) maintain an equal distance between them but decrease in length towards the North and South Poles. On a chart, the shape of the Earth is projected onto a cylinder and unfolded to a flat surface, on which parallels and meridians remain at right angles to each other, so the meridians do not run towards each other. To be able to draw a path as a straight line on the map, the parallels towards the North and South Pole are also stretched. This method of the expanding map or Mercator projection, in which the scale slowly expands, is applied to all British charts.

Digital marine charts

Electronic marine charts come in two types: raster charts and vector charts. A raster chart (RNC Raster Navigational Chart) is an exact copy of a paper chart, built-up from pixels and often digitised with the help of a scanner. A vector map (ENC Electronic Navigational Chart) is built-up in layers from a digital file (database) with components, co-ordinates and information.

Co-ordinate format

On all British charts, the minutes are divided into tenths along the chart edge. With GPS receivers and electronic charts, different and sometimes rather confusing, ways of noting positions may be used. In the examples below, the second method corresponds best to the paper nautical chart but still requires a little thought to be carried out!

| * D.d | = | Decimal/degrees (to six decimal places): |

| 52.369647 N |

| 005.233957 E |

| * DM.m | = | Degrees/Minutes/thousandths of a minute: |

| 52 22.179 N |

| 005 14.037 E |

| * DMS.s | = | Degrees/Minutes/Seconds/hundredths of a second: |

| 52 22 10.73 N |

| 005 14 02.24 E |

Nautical mile

The shortest distance between any two points on Earth is reached along a great circle, the distance of which is equal to a meridian. One degree on such a circle is equal to 60 minutes and one minute is equal to 60 seconds. In practice, however, tenths of minutes are used. The distance that one minute covers on a meridian is very important.

1 minute = 1 nautical mile = 1,852 metres

Nautical chart symbols, abbreviations and terms

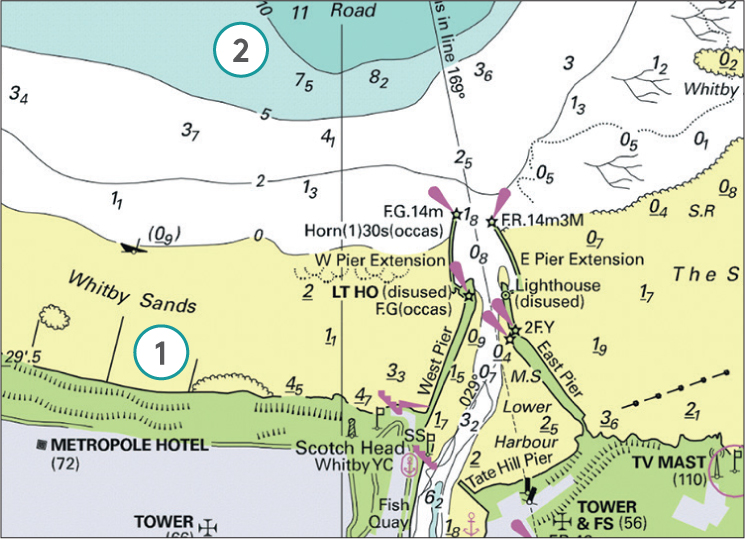

The nautical chart is used for orientation, voyage planning and the recording of positions, directions and bearings. A wealth of information is available, so much so that the use of symbols and abbreviations is essential.

The use of colour is also important. On British Admiralty charts, land masses are yellow, areas that dry are green and water is blue or white according to its depth.

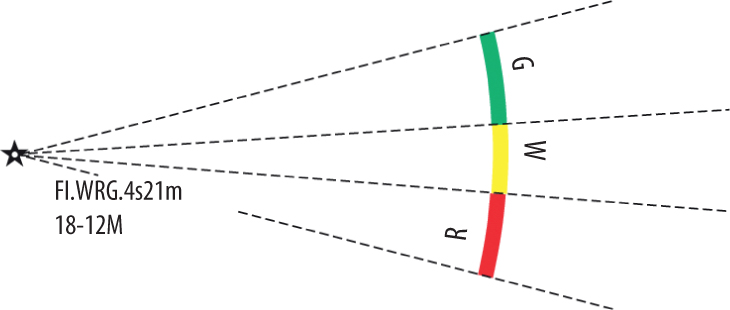

Buoys, beacons and lighthouses with associated light characteristics are particularly important, as are other visual landmarks. The exact position is indicated by an open circle. Water depths are indicated up to the reduction plane (see ) and are connected by lines in areas of equal depth.

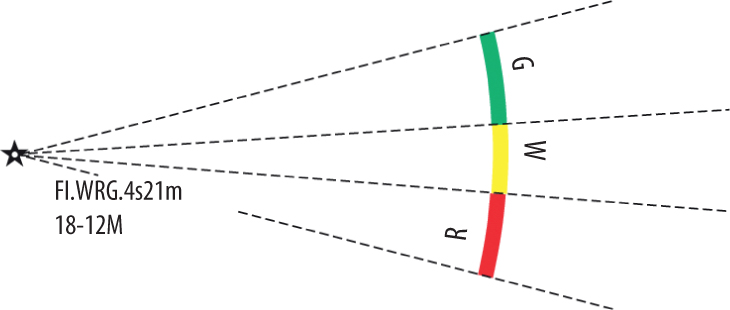

Sector light on multi-coloured chart. The elevation is 21 metres. The nominal range of the white light is 18 nautical miles. The range of the green light is 12 nautical miles and the red light is in between

Notice to Mariners

In accordance with international regulations, laid down in SOLAS (International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea), nautical products, including sea charts, must be kept up-to-date. Therefore, the UK Hydrographic Office (UKHO) publishes weekly Notices to Mariners (NMs) containing a comprehensive list of corrections to charts. The NMs are free to access and can be found at www.admiralty.co.uk/maritime-safety-information/admiralty-notices-to-mariners