by Ian McDonald

Australian team manager, 1986-1998

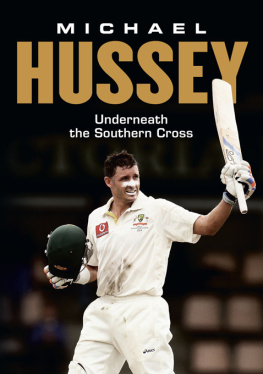

IN AUSTRALIAN DRESSING ROOM folklore, the player chosen by his teammates to jump on a table and lead the victory chant after an Aussie win, by reciting Under the Southern Cross, always typifies the tough, never-give-in image that is the traditional hallmark of Australian teamsa man who wears the famous baggy green with intense pride.

Such a man is Ian Healy. It is a tribute to his character as a player that he was chosen to follow his boyhood hero, Rod Marsh, Australias most famous little Aussie battler Allan Border, and the rock-like Tasmanian David Boon in filling this role. When Boon named him as his successor in January 1996, Ian Healy took over with tremendous pride and fulfilled the role with passion and gusto.

Thats the way he was behind the wickets and thats the way he played his cricket. He was a tough, uncompromising team man with a fierce determination to win. Of course, wicketkeepers are tough nuts anywaytheyre a special breed, an integral part of the team with play revolving around them, always cajoling their teammates, the sort of blokes you would like beside you if you were fighting in the trenches. Australia has a proud tradition of producing great keepers, stretching back to Jack Blackham in the 19th century. The toughness of the fraternity was typified by Bert Oldfield during the 193233 Bodyline series, when he had his skull cracked standing up to the English bumper barrage. In more modern times, there have been Don Tallon, who was in Don Bradmans famous 1948 team, Wally Grout, who was with Richie Benauds teams in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Rod Marsh, who was in Ian and Greg Chappells teams, and then Heals. There have been other good keepers, but when it comes to the best ever, the argument inevitably narrows down to the three QueenslandersTallon, Grout and Healyand the West Australian, Marsh. Ive been fortunate to see all four in action and each brought his own individuality, flair and touch of class to the toughest role in cricket.

Comparing players from different eras is difficult, but there are two indicators that place Healy at the top of the field. Statistically, he is Australias greatest keeper, having passed Rod Marshs record of 355 dismissals, and in 19992000 he was selected as wicketkeeper in the ACBACA Team of the Century. He was in elite company in that team, alongside Sir Donald Bradman, Arthur Morris, Bill Ponsford, Neil Harvey, Greg Chappell, Keith Miller, Shane Warne, Bill OReilly, Ray Lindwall, Dennis Lillee and Allan Border. It was apt that Warne was selected in that team with Healy, because television viewers throughout the world had become used to hearing Heals yelling out through the stump microphone, Bowled Warney! The combination of the great legspinner and the astute Healy became the most lethal in world cricket, a combination that ranks with that of Rod Marsh and Dennis Lillee, because like Healy bettering Marshs record, Warne also broke Lillees Australian Test wicket-taking record.

Healys ability to keep so well to the prodigious spin of Warne was a pleasure to witness, but so too were his performances keeping to pacemen such as his mate Craig McDermott, who rose from the ranks of Queensland junior cricket with him, the volatile Merv Hughes, and then Glenn McGrath, who is well on the way to breaking a few records himself.

There Heals crouched behind the stumps, sleeves rolled down, shirt collar turned up most of the time, and the baggy green pulled very firmly on his blonde head. Always well prepared, because thats the nature of the man, he was also always well organised and very fussy about neatness. It must have something to do with the sun in Queensland, because in my 13 years as Australian Team Manager, Heals, Craig McDermott and Allan Border stood out as the neatest and best organised players in the dressing room. Away from these players places, it often looked as if a cyclone had scattered gear everywhere.

If ever there was a role model for kids, Heals was it. The country boy from Biloela got to the top and stayed there through sheer hard work, aided by a fierce determination to succeed and the courage to overcome and play with painful injuries. Earlier in his career I used to wonder where hed disappeared to in the morning before breakfast. Some players jog, swim or go to the gym but Heals wasnt to be seen, until one morning I went to the basement carpark at our Melbourne hotel and found him with his inner gloves on throwing and catching a golf ball as it rebounded from the wall, making sure his footwork and glovework were rightall to ensure that when he took the field he would be able to move his feet into position quickly, ready to take the ball on the inside of his body. Like Grout and Marsh, he worked on the principle that you should be in position to take the ball on your feet and only dive if you have to.

Popular with his teammates, he was always one of the boysgeeing them up on the field and celebrating with them when they won. His popularity didnt always extend to officialdom, because sometimes he over-celebrated, and he was a strong advocate for players rights, was at the forefront of the push for a Players Association and was involved in the 1997-98 players dispute with the ACB. Heals is as honest as they come, but sometimes his forthright attitude ruffled a few official feathers. Despite this he had their respect, because he was doing it the only way he knowsfighting to get the best for his team.

After the Allan Border era ended in 1994, Healy, Mark Taylor, Steve and Mark Waugh and David Boon became the experienced backbone of a team that rose to No. 1 in the world. This book takes you on that trip with him. His career ended at the Gabba in 1999, his family were all therehis wife Helen and their three kids, his mother and the rest of the Healy tribeand as he was driven around the ground in an open car the crowd gave him a standing ovation.

It was a fitting farewell for a great Australian keeperand a great bloke.

by Geoff Armstrong

I FIRST SAT DOWN to talk to Ian Healy about his autobiography on January 19, 2000, the day after hed been named as the wicketkeeper in Australias Team of the Century. I asked him straight away what it was like to be thought of so highly, above all the other keepers whod dreamed of appearing in grade cricket, never mind playing for Australia. As a boy playing with his brothers in the backyard, against the men on Saturday afternoons, or even in his sleep, he wouldnt have dared imagine, surely, that his cricket life would end with such an achievement, being part of a team as renowned as this.

Mate, its kind of surreal, was his response. He was extremely honoured, and clearly at least a little overawed to have his name included in such exalted company. More than any other high-profile cricketer I have met, I was struck by what an unaffected bloke he was. Nothing in the six months that followed, as we trawled through his life and cricket experiences and built the chapters that make up this book, changed that impression.

Later, his wife Helen told me the story of a very excited and emotional husband, standing behind a curtain at that Team of the Century function and on his mobile phone as he waited to have his photo taken with his new teammates. If Id known this was going to happen, he told her, Id have got you and Mum down here. It was a simple wishone he has emphasised whenever hes talked to me about that daywhich genuinely reflects the gratitude he feels for his familys support, from the early days, the best part of 30 years ago, when his parents began to help shape his cricket life, to the long tours through the 1990s when Helen stayed behind to keep house, offer support and for long periods raise their three children on her own.