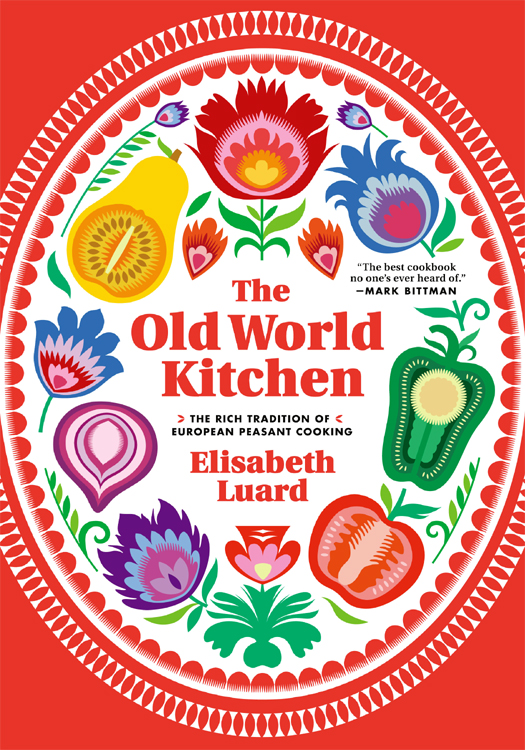

THE OLD WORLD KITCHEN:

THE RICH TRADITION OF EUROPEAN PEASANT COOKING

Originally pubished by Bantam in October 1987

Copyright 1987 by Elisabeth Luard

All rights reserved

Drawings by Elisabeth Luard

First Melville House printing: November 2013

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following: Ernest Hemingway, excerpted from Dangerous Summer. Copyright 1960 by Ernest Hemingway, copyright 1985 by Mary Hemingway, John Hemingway, Patrick Hemingway, and Gregory Hemingway. Reprinted with permission from Charles Scribners Sons.

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013950828

ISBN: 978-1-61219-269-7

eBook ISBN: 978-1-61219-269-7

v3.1

For my children,

Caspar, Francesca, Poppy, and Honey,

without whom there would not have been a book

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Over the years many people from many countries have helped me in many ways with the preparation of this book, notably those whose names appear in the text. In addition to them, I owe particular gratitude for patient assistance in cultural and culinary matters to the staff of the London Library, Betty Molesworth Allen, Maurice de Ponton dAmecourt, Bernard Aug, Elisabeth and Odbjorn Andreassen, Viviker and Richard Bernstrom, Tomas Bianchi, Mrs. Vasili Frunzete, Alfred Grisel, Christian Hesketh, Vane Ivanovic, Frau Klein, Mitte Lhoest, Cecilia McEwen, Maureen McGlashan, Kiki Munchi, Ilhan and Ruya Nebioglu, May Pocock, Dr. Astri Riddervold, Monica Rawlins, Erzbet Schmidl, Iolanda Tsalas, and Jacqueline Weir. Above all, my thanks to Priscilla Wintringham-White, who valiantly tested the recipes in my kitchen; to Fran McCullough, who has been inspiration, mentor, and midwife to the American edition of this book; and to my beloved husband and companion-at-table, Nicholas.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The market stalls in the southern Spanish port of Algeciras, among which as a young wife and new mother I found myself and my basket one bright June morning in 1965, had very little in common with the shelves of the city supermarkets where I had been accustomed to shop. I was bewildered but intrigued. A childhood spent in several distant parts of the world with my parents, foreign-posted diplomats, had given me an early appetite for street-corner food. This youthful enthusiasm had also left me with an unshakable optimism that I could eat, and usually appreciate, anything that was palatable to any other human. I had discovered a single exception. Monday dinner, at the English boarding school to which I was periodically returned, invariably consisted of mouse-gray mincemeat accompanied by wet toast. I had never managed to stomach that, not even with an appetite sharpened by outdoor swimming at 7 A.M. on an English March morning.

The Algeciras market could not have produced a school dinner in a month of Mondays. The vegetable stalls which formed its outer ring were piled with unfamiliar greenery: a heap of tagarnina, thistle stems waving tarantulalike green extremities; bundles of fresh garlic, like ice-white onions; smiling pink segments of watermelon; purple-tipped cardoons tied as rosebud bouquets. Between the stalls little encampments of Gypsy children presided over sacks of tiny snails with translucent bodies and inquiring pin-stalk eyes, flanked by baskets of wild mushrooms and bundles of slender wild asparagus bound with esparto grass. The fish vendors, raised above their customers on a line of white-tiled stalls dripping seawater, bellowed out their wares: octopus, squid, cuttlefish, monkfish, sea bream, bass, anchovies, and sardines. The poultry market was livelier still. There were bunches of chickens squawking on the ends of brawny arms, a blue-eyed goose, and a few mournful turkeys gobbling in one cornerno Andalusian housewife would have trusted a dead barnyard bird as far as she could chase it. The spice lady must have had fifty open sacks around her: almonds, six kinds of tea, bay leaves, dried garlic and paprika, cloves and cinnamon bark, thyme, rosemary, marjoram, coriander, poppy seeds, licorice twigs, pumpkin seeds, dozens more. Often she would be asked to make up a flavoring mix: a paper twist of the herbs to spice four kilos of snails, to prepare a side of pork in paprika lard, to provide the aromatics for ten kilos of olives. Later I learned to rely on her expertise myself.

Mara, my neighbor up the valley where I and my growing family settled, was my mentor in those first years. As se hace, she would patiently explain, This is how it is done, as I struggled with the ink sacs in the cuttlefish, or attempted to cook the chick-peas without soaking them first. Very often she would come by with gifts of food for my childrenhoney from her uncles hives, the first figs, wrapped in one of their own leaves, from the tree in her fathers garden, oil biscuits which she had made after bread-baking day.

My family and I saw the seasons pass in the valley. The children went to the local school, where they learned along with the three Rs how to trap and skin rabbits, how to stake pastures to hold the forests hogs, and how to mend a hand-drawn threshing sled made to a design unchanged since the Iron Age. With Maras advice and under her tutelage we acquired a donkey, a kitchen garden, and a household pigthe last, I stipulated, only if Mara helped me at its final hour. The pig thrived mightily on the scraps from my kitchen. Finally, on a late October day deemed suitable, the moon being in the right quarter and the pig having been fattened to the correct weight on acorns from the surrounding cork oaks, Maras husband and brother-in-law arrived at sunrise to prepare for the dreaded event. Soon afterwards Mara, her cousins, and her mother appeared to help with the kitchen labor. The children were packed off to school early, and all day we worked salting hams, seasoning sausages, stuffing black puddings, and spicing chorizos. That evening, as she prepared the traditional celebration meal of chcharros, pork skin fried crisp; kidneys in sherry; and garlic-fried liver which follows a country matanza (butchering), Mara finally asked the question which made me embark on this book.

Tell me, she said, her voice sympathetic as she leaned over the table and restored control of the sausage casing to my clumsy fingers for the fifth time, I have been wanting to ask you ever since you and your family arrived, but I did not wish to seem inquisitive. Please forgive me, but did your mother teach you nothing at all?

From then on, Mara became a surrogate mother in the old ways of the countryside to all of us. Seven years later, when we departed for the Languedoc to give the children a years schooling in France, she came down the hill to see us on our way. As we climbed into our crammed vehicle, she handed a bundle in through the window. Inside was a bag of dried sunflower seedsthe childrens favorite