Perspective

Without Pain

Phil Metzger

NORTH LIGHT BOOKS

Cincinnati, Ohio

www.artistsnetwork.com

Perspective Without Pain. Copyright 1992 by Phil Metzger. Manufactured in China. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published by North Light Books, an imprint of F + W Publications, Inc., 4700 East Galbraith Road, Cincinnati, Ohio 45236. (800) 289-0963. First edition.

Other fine North Light Books are available from your local bookstore, art supply store or direct from the publisher.

10 19

Distributed in Canada by Fraser Direct

100 Armstrong Avenue

Georgetown, ON, Canada L7G 5S4

Tel: (905) 877-4411

Distributed in the U.K. and Europe by David & Charles

Brunei House, Newton Abbot, Devon, TQ12 4PU, England

Tel: (+ 44) 1626 323200, Fax: (+ 44) 1626 323319

E-mail: postmaster@davidandcharles.co.uk

Distributed in Australia by Capricorn Link

P.O. Box 704, Windsor, NSW 2756 Australia

Tel: (02) 4577-3555

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Metzger, Philip W.

Perspective without pain/Phil Metzger.1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-89134-446-9

ISBN-10: 0-89134-446-2

1. Perspective. 2. DrawingTechnique. I. Title

NC750.M48 1992

742dc20

91-43309

CIP

Designer: Clare Finney

To Shirley Porter

Acknowledgments

When North Light asked me to consider writing a book on perspective, my greedy eyes lit up and I said, SURE! I figured perspective was a snap and I could knock it off in a few weeks. Months later and somewhat chastened, I realized that there was more to the subject than met the eye. There are thick books about perspective that dig deep into the mathematics and mystery of the subject. My job was to come up with a book that dispelled the mystery and concentrated on those aspects of perspective that someone in the fine arts would need to know. If you're an architect or an engineer, this book is not for you. But if you draw and paint as a hobby or for a living, I think you'll find it just about right.

I want to thank two people who participated in producing this book: Linda Sanders, my excellent editor at North Light, who kept steering me in the direction a book of this kind must take and really worked with me rather than sit back and accept whatever I threw her way; and Shirley Porter, who supplied a couple of the sketches in the book, but who mainly read my prose before I submitted it to Linda and savagely deleted most of the dumber things I had written. I honestly thank you both.

Perspective: the science of painting and drawing so that objects represented have apparent depth and distance.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary

Contents

Part One:

The Basics

Part Two:

Boxes and Beyond

Part Three:

Curves and Inclines

Part One:

The Basics

If you're like most painters, you probably work hard at trying to make a flat surface appear to have depth. You look at the three-dimensional scene in front of you and sweat to get it down convincingly on your two-dimensional paper or canvas, but sometimes you're frustrated. A distant object doesn't look so distant on your paper, or an object seems the wrong size compared to another, or a building looks as though it's sliding off the page.

You're not alone. We all struggle throughout our careers to make our drawing more convincing. Some teachers say that our drawing problems are all magically solved once we learn to see better. If you see better, so the argument goes, you'll automatically draw better.

I think that's too simplistic. In order to draw well, four things are needed:

1. Seeing

2. Understanding

3. Practice

4. Technique

Seeing

Seeing means looking at the subject you're about to draw and analyzing it as a bunch of abstract shapes, colors, values and textures.

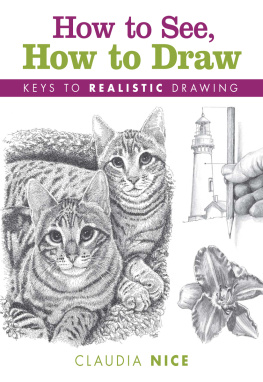

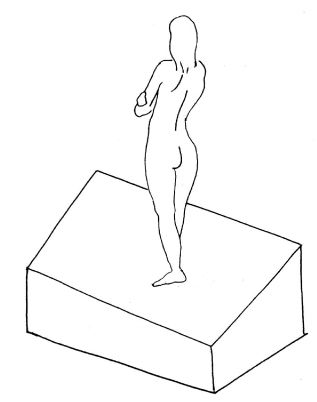

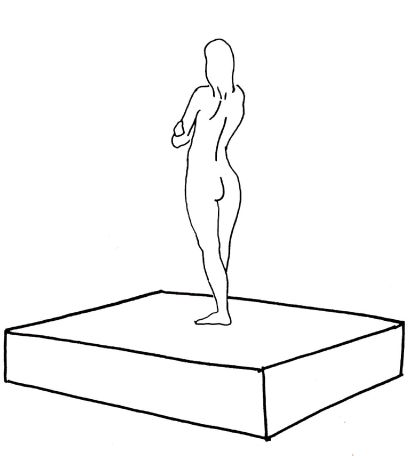

You must overcome what you know about the object. An editor at North Light Books who teaches figure drawing says that students drawing a model standing on a platform often have trouble drawing the platform correctly. They know the surface of the platform is a rectangle, and tend to draw it that way. The result is something like the drawing at upper right.

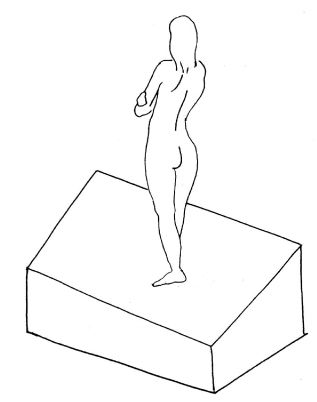

If they were to draw what they actually see, rather than what they know, they'd come up with something like the second sketch.

The Basics

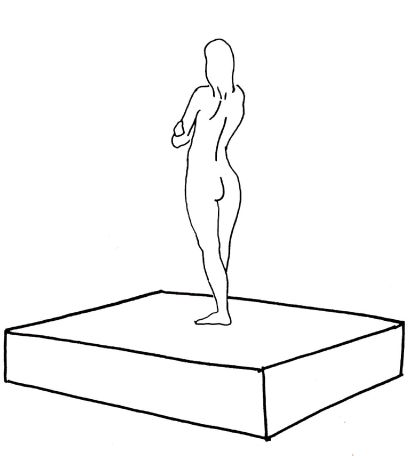

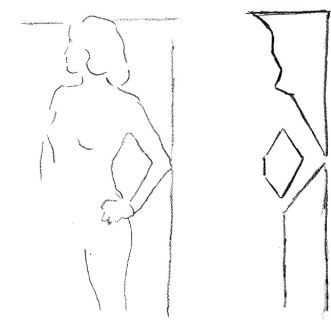

Try to forget about what the thing really is. Instead of seeing a person standing on a platform, try to see first a combination of shapes. Don't concentrate on an arm with elbow outward and hand on hip, as at bottom left.

Instead, first try seeing shapes only, as shown at bottom right.

You'll find that as you get adjacent shapes right, the figure will gradually emerge. When the shapes are right relative to one another, add color, texture, shading, and so on. As you do so, these additions will force you to reconsider the shapes you came up with that you thought were so perfect. For example, when you get the value (the lightness or darkness) of the space between the arm and the body fairly correct, you may find that the shape of that space no longer seems right. Everything in a drawing affects everything else. So you fiddle with the shape, and play this back-and-forth game until you feel comfortable with the object you've drawn.

Understanding

Understanding means knowing what's really going on in an object you're trying to draw, even though from where you're standing the object doesn't look at all correct. The model's platform is a good example. You know it is rectangular but all you can see is that crazy shape! You may wonder what good it does to know what shape a thing really has if the idea is to draw it as you see it. Rembrandt had it about right when he said, If you want to paint an apple you've got to be an apple! If you want to paint something convincingly you've got to know it intimately. (That might be a little easier with an apple than with a live model!) Seeing accurately and abstractly gives you the ability to render a subject with mechanical exactness; understanding the subject enables you to give it soul.

Practice

Practice is what enables you to put your ability to see and understand to good use. It's the training you need to translate what you see and understand in your brain into shapes and colors and shades and textures on a piece of paper or a canvas. This book will offer you plenty of exercises for practicing the ideas discussed.

Technique

To practice anything you need to learn proven techniques developed by others and add your own as you gain experience. One set of drawing and painting techniques used by artists for centuries is called perspective.

Perspective is simply a set of techniques used to draw a three-dimensional scene on a two-dimensional surface. In other words, perspective is an approach toward getting the illusion of depth in a drawing or painting. We'll play with several perspective techniques in this book. They are all simple once you get to know them, and they should all become part of the background knowledge every painter comes to use quite automatically.

Next page