In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher is unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Thank you for buying this ebook, published by Hachette Digital.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and news about our latest ebooks and apps, sign up for our newsletters.

Sign Up

Or visit us at hachettebookgroup.com/newsletters

For more about this book and author, visit Bookish.com.

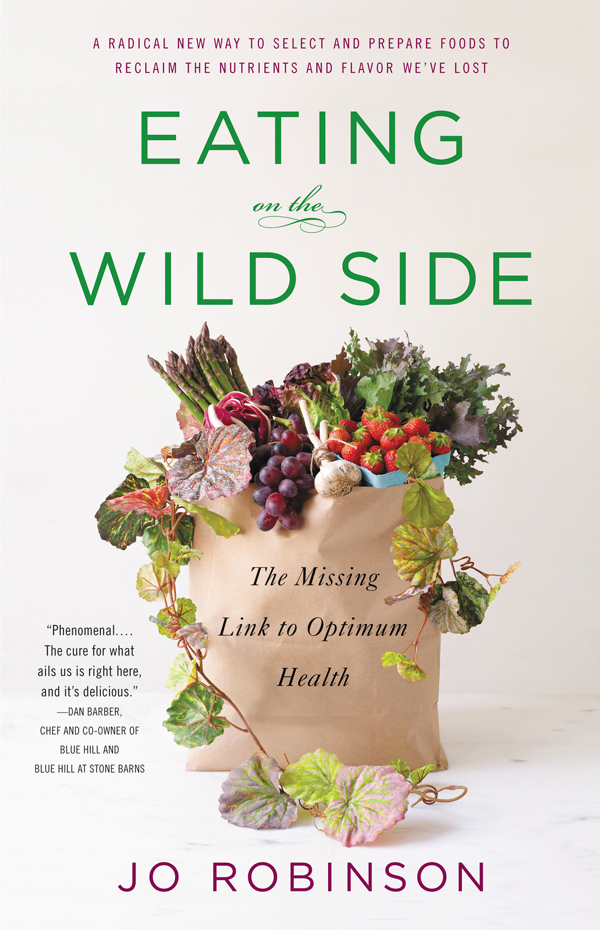

Copyright 2013 by Jo Robinson

Illustrations by Andie Styner of Roobiblue Studios

Cover design by Ploy Siripant

Cover photograph by Ellen Silverman

Cover Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at . Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First ebook edition: June 2013

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN: 978-0-316-22795-7

I dedicate this book to all the researchers, food activists,

and plant breeders who are working to preserve the

genetic diversity of our fruits and vegetables and to

enhance their nutritional content. Through their efforts, we

can begin to reclaim a wealth of nutrients that we,

unwittingly, removed from our diet over a period of

ten thousand years.

W here do our fruits and vegetables come from? Not from the supermarket, of course. Thats just where they are sold. Nor do they come from large commercial farms, local farms, or even our backyard gardens. Thats where they are planted, tended, and harvested. The fruits and vegetables themselves came from wild plants that grow in widely scattered areas around the globe. Most of our blueberries are descended from wild swamp blueberries that are native to the Pine Barrens of New Jersey. The wild ancestor of our beefsteak tomato is a berry-size fruit that grows on the flanks of the Andes Mountains. Our hefty orange carrots are related to scrawny purple roots that grow in Afghanistan. When our distant ancestors invented farming ten thousand or so years ago, they began altering these and other wild plants to make them more productive, easier to grow and harvest, and more enjoyable to eat. To date, four hundred generations of farmers and tens of thousands of plant breeders have played a role in redesigning native plants. The combined changes are so monumental that our present-day fruits and vegetables seem like modern creations.

Consider the banana, our most popular fruit. The wild ancestor of the banana grows in Malaysia and parts of Southeast Asia. The bananas come in a multitude of shapes, colors, and sizes. Most of them are chock-full of large, hard seeds. Their skins are so firmly attached that you have to cut them off with a knife. Take a bite of the dry, astringent flesh and youd wonder why you went to the trouble. Over several thousand years, we clever humans have transformed this barely edible fruit into the Cavendish banana, the yellow, long-fingered banana that is sold in all our supermarkets. We love the Cavendish for its zip-off peels, sweet and creamy flesh, and the fact that its seeds have been downsized to mere dots. The seeds are not viable, of course, but seeds are not needed when plants are grown from cuttings, which is how all our bananas are propagated. Generation after generation, we have reshaped native plants and made them our own.

THE LOSS OF VITAMINS, MINERALS, PROTEIN, FIBER, AND HEALTHFUL FATS

Unwittingly, as we went about breeding more palatable fruits and vegetables, we were stripping away some of the very nutrients we now know to be essential for optimum health. Compared with wild fruits and vegetables, most of our man-made varieties are markedly lower in vitamins, minerals, and essential fatty acids. A wild plant called purslane has six times more vitamin E than spinach and fourteen times more omega-3 fatty acids. It has seven times more beta-carotene than carrots.

Most native plants are also higher in protein and fiber and much lower in sugar than the ones weve devised. The ancestor of our modern corn is a grass plant called teosinte that is native to central Mexico. Its kernels are about 30 percent protein and 2 percent sugar. Old-fashioned sweet corn is 4 percent protein and 10 percent sugar. Some of the newest varieties of supersweet corn are as high as 40 percent sugar. Eating corn this sweet can have the same impact on your blood sugar as eating a Snickers candy bar or a cake doughnut.

Today, most health experts agree that the most healthful diet is one that is high in fiber and low in sugar and rapidly digested carbohydrates. This regimen is referred to as a low-glycemic diet because it helps keep our blood glucose at optimum levels. A low-glycemic diet has been linked to a reduced risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic inflammation, obesity, and diabetesour five modern scourges. Wild fruits and vegetables are the original low-glycemic foods.

A DRAMATIC LOSS OF PHYTONUTRIENTS

Within the past two decades, plant scientists around the world have discovered another major difference between wild plants and our modern varieties: the plants that nature made are much higher in polyphenols, or phytonutrients. (In this book, I will use the terms phytonutrients and bionutrients interchangeably. Phyton is the Greek word for plant.) Plants cant fight their enemies or hide from them, so they protect themselves by producing an arsenal of chemical compounds that protect them from insects, disease, damaging ultraviolet light, inclement weather, and browsing animals.

More than eight thousand different phytonutrients have been identified to date, and each plant produces several hundred of them. Many of the compounds function as potent antioxidants. When we consume plants that contain high amounts of bioavailable antioxidants, we get added protection against noxious particles called free radicals that can inflame our artery linings, turn normal cells cancerous, damage our eyesight, increase our risk of becoming obese and diabetic, and intensify the visible signs of aging. Other phytonutrients are involved in the communication between our cells, and yet others alter our genes. A number of small-scale studies have shown that select bionutrients in plants can also enhance athletic performance, reduce the risk of infection, fight the flu, lower blood pressure, lower LDL cholesterol, speed up weight loss, protect the aging brain, improve mood, and boost immunity.

Next page