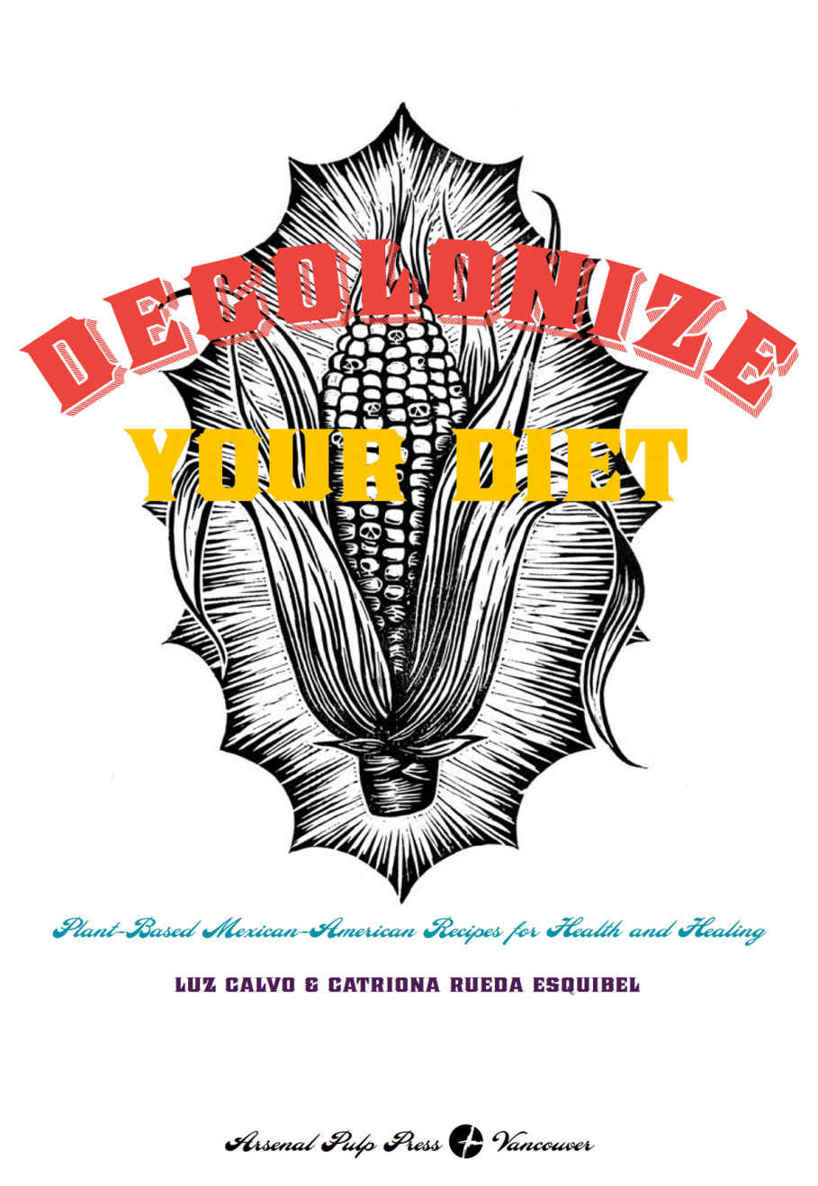

DECOLONIZE YOUR DIET

Copyright 2015 by Luz Calvo and Catriona Rueda Esquibel

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any part by any meansgraphic, electronic, or mechanicalwithout the prior written permission of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may use brief excerpts in a review, or in the case of photocopying in Canada, a license from Access Copyright.

ARSENAL PULP PRESS

Suite 202211 East Georgia St.

Vancouver, BC V6A 1Z6

Canada

arsenalpulp.com

The author and publisher assert that the information contained in this book is true and complete to the best of their knowledge. All recommendations are made without the guarantee on the part of the author and publisher. The author and publisher disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information. For more information, contact the publisher.

Note for our UK readers: measurements for non-liquids are for volume, not weight.

Design by Gerilee McBride

All photographs, prop styling, and food styling by Tracey Kusiewicz / Foodie Photography

Cover illustration: Maz Sagrado by Veronica Perez

Editing by Susan Safyan

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication: Calvo, Luz, 1960, author

Decolonize your diet: plant-based Mexican-American recipes for health and healing / Luz Calvo & Catriona Rueda Esquibel.

Includes index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55152-593-8 (epub)

1. Vegetarian cooking. 2. Mexican American cooking. 3. Plants, EdibleHealth aspects. 4. Cookbooks. I. Esquibel, Catrina Rueda, 1965, author II. Title.

TX837.C34 2015 641.5'636

C2015-903460-4

C2015-903461-2

With our heart in our hands and our hands in the soil

CONTENTS

From the first page to the last, it is clear that Luz Calvo and Catriona Rueda Esquibels book is motivated by love: their love for each other, for their communities, for the delicious food of their ancestors, and for our planet. Their plant-forward recipes explore the healthiest aspects of Mexican cuisine. I see Decolonize Your Diet as a playful mix of cultural reclamation, food politics, and vegetarian recipes. Some of the recipes are classic healthy dishes that have always been a mainstay of Mexican cuisinea slow-cooked pot of beans or a zesty cactus salad. In others, Luz and Catriona bring their farm-to-table sensibility to traditional dishes such as their , p. 193).

I am enthusiastic about Decolonize Your Diet because its mission so closely reflects my own. In Afro-Vegan, I focus on farm-fresh, Afro-diasporic fare and share the rich and often painful histories of people of African descent as expressed through food. As I travel the country giving talks, I have encountered Latinas and Latinos who appreciate my work and want to apply a similar approach to their own cooking practice. I always refer them to Luz and Catriona. Drawing from their research on traditional Mesoamerican cuisine, they demonstrate the ways that home-cooked meals carry history, memory, and stories, and connect contemporary Latinas/os to their ancestors. Along with my own work, Decolonize Your Diet is part of a larger movement utilizing ancestral knowledge to help communities of color respond to the public health crises and the decimation of our food systems foundation, brought upon us by the industrialized, Western diet. Our collective goal is to empower people to choose wholesome foods to improve the physical and spiritual health of our families, communities, and Mother Earth. I invite you to sample the flavors of pre-Conquest Mexico as you join us in the project of decolonizing our diets.

Bryant Terry, James Beard Foundation Leadership Award recipient and author of Afro-Vegan: Farm-Fresh African, Caribbean, and Southern Flavors Remixed

Photo: Miki Vargas

The recovery of the people is tied to the recovery of food, since food itself is medicine, not only for the body, but for the soul, and for the spiritual connection.

Winona LaDuke

Libradita Tafoya Esquibel with her youngest children and a granddaughter. Northern New Mexico, 1952

In Catrionas Words

My father Alfonso describes growing up in rural, northern New Mexico in the 1940s and 50s. The family enjoyed a diverse diet ensured by the labor of his mother, Libradita Tafoya Esquibel. Her kitchen garden produced squash and other vegetables. She gathered wild greens and herbs and cooked seasonal Lenten dishes to accommodate the familys ritual abstinence from meat. She put up summers fruit for winter eating. She made thick, bready white flour tortillas and raised baby chicks next to her stove every year to provide eggs and meat for her family. When my grandmother left her abusive marriage and went to live with her grown daughters in Colorado, my dads world changed dramatically. Without my grandmothers unpaid labor to provide a healthy diet, my father and the remaining family members could afford only the cheapest, most easily prepared meals, most often canned foods. Eventually, my fathers family migrated to Colorado, then Wyoming, and finally Los Angeles. Most of the members of my fathers generation developed type 2 diabetes as adults.

When Luz and I started to get to know each other in 1995, food was always part of the scene: I brought my vegetarian pozole to Luzs potluck. The first date dinner I cooked for Luz was (p. 96). Those two, along with my red chile tofu enchiladas, were the only from scratch meals I knew how to make. After we moved in together in 1996, my sister emailed me her mother-in-laws recipe so we could cook homemade flour tortillas together. Our song was the classic Sabor a M.

The next nine years took us all over the country, from Santa Cruz, California (where we met as graduate students), to Las Cruces, New Mexico (my first job, while Luz wrote a dissertation and trained to run a marathon), to Columbus, Ohio (Luzs first tenure-track gig). In Las Cruces, the summers were so hot that we had to learn new ways of cooking and eating. Luz would cook first thing in the morning and then chill the foods so we could have a cold salad for dinner. Pasta salad, rice salad, bean salad: we had a whole repertoire of recipe ideas that we could plan our shopping and meals around. In Ohio, we had the perfect little kitchen, set up so that I could play sous chef and chop on one side of the counter while Luz spun and sauted and played master chef on the other side. In 2005, we moved back to northern California when we got our current jobs at Cal State East Bay and San Francisco State University, and we thought we could finally catch our breath, now that we were home again. One of the first things we did was buy a lemon tree. Luz planted it in a big pot, and we cared for it on our deck. The lemon tree was a symbol of our happy return to California.

Next page