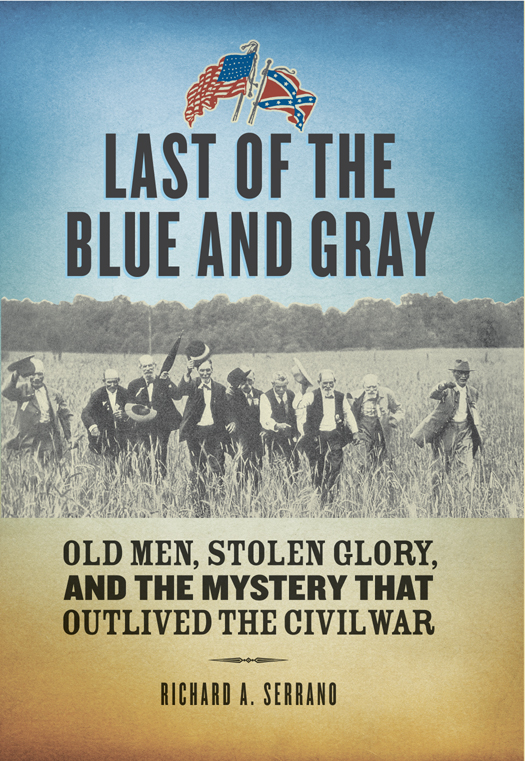

Williams Walter Washington - Last of the blue and gray : old men, stolen glory, and the mystery that outlived the Civil War

Here you can read online Williams Walter Washington - Last of the blue and gray : old men, stolen glory, and the mystery that outlived the Civil War full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: United States, United States, year: 2013, publisher: Smithsonian, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Last of the blue and gray : old men, stolen glory, and the mystery that outlived the Civil War

- Author:

- Publisher:Smithsonian

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- City:United States, United States

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Last of the blue and gray : old men, stolen glory, and the mystery that outlived the Civil War: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Last of the blue and gray : old men, stolen glory, and the mystery that outlived the Civil War" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Richard Serrano, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for the Los Angeles Times, pens a story of two veterans in the late 1950s gearing up for the Civil War centennial--one claiming to be the last Confederate soldier and one claiming to be the last Union soldier--and one of them a fraud. Last of the Blue and Gray sets the stage for the centennial anniversary of our nations most difficult period, with notions of ethics and honor and also dishonesty and disgrace. In the late 1950s, as America prepared for the Civil War centennial, two very old men lay dying. Albert Woolson, 109 years old, slipped in and out of a coma at a Duluth, Minnesota, hospital, his memories as a Yankee drummer boy slowly dimming. Walter Williams, at 117 blind and deaf and bedridden in his daughters home in Houston, Texas, no longer could tell of his time as a Confederate forage master. The last of the Blue and the Gray were drifting away; an era was ending. Unknown to the public, centennial officials, and the White House too, one of these men was indeed a veteran of that horrible conflict and one according to the best evidence nothing but a fraud. One was a soldier. The other had been living a great, big lie-- Read more...

Abstract: In the late 1950s, as America prepared for the Civil War centennial, two very old men lay dying. Albert Woolson, 109 years old, slipped in and out of a coma at a Duluth, Minnesota, hospital, his memories as a Yankee drummer boy slowly dimming. Walter Williams, at 117 blind and deaf and bedridden in his daughters home in Houston, Texas, no longer could tell of his time as a Confederate forage master. The last of the Blue and the Gray were drifting away; an era was ending. Unknown to the public, centennial officials, and the White House too, one of these men was indeed a veteran of that horrible conflict and one according to the best evidence nothing but a fraud. One was a soldier. The other had been living a great, big lie--

Richard Serrano, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for the Los Angeles Times, pens a story of two veterans in the late 1950s gearing up for the Civil War centennial--one claiming to be the last Confederate soldier and one claiming to be the last Union soldier--and one of them a fraud. Last of the Blue and Gray sets the stage for the centennial anniversary of our nations most difficult period, with notions of ethics and honor and also dishonesty and disgrace. In the late 1950s, as America prepared for the Civil War centennial, two very old men lay dying. Albert Woolson, 109 years old, slipped in and out of a coma at a Duluth, Minnesota, hospital, his memories as a Yankee drummer boy slowly dimming. Walter Williams, at 117 blind and deaf and bedridden in his daughters home in Houston, Texas, no longer could tell of his time as a Confederate forage master. The last of the Blue and the Gray were drifting away; an era was ending. Unknown to the public, centennial officials, and the White House too, one of these men was indeed a veteran of that horrible conflict and one according to the best evidence nothing but a fraud. One was a soldier. The other had been living a great, big lie

Williams Walter Washington: author's other books

Who wrote Last of the blue and gray : old men, stolen glory, and the mystery that outlived the Civil War? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.