This book is dedicated to Dame Elisabeth Murdoch, a great admirer of Sydney and Joice Loch. Dame Elisabeths financial and psychological support during the long process of writing and editing Sydney Lochs life story and the account of his Gallipoli experiences has been invaluable.

To Hell and Back is also dedicated to the memory of the late Iain Loch, son of Sydneys brother Charles. For over a year we communicated with Iain by phone and e-mail. Although he became ill during that time, he was always helpful in providing vital information about Loch family history. Unfortunately, Iain Loch did not live long enough to see this book in print.

Table of Contents

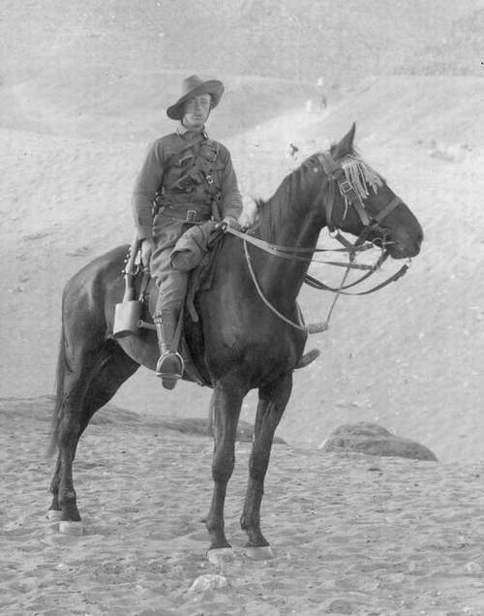

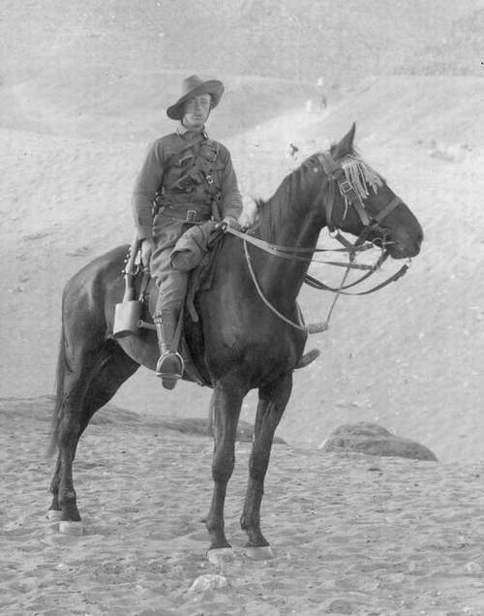

COURTESY GEORGINA LOCH JARVENPAA

Sydney Loch on his horse The Director (the only photograph of Sydney as an Anzac that was not destroyed in World War II).

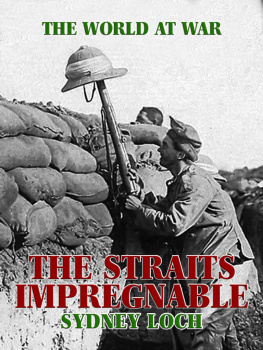

THE STRAITS IMPREGNABLE THE BEST BOOK ON GALLIPOLIBANNED BY THE CENSOR

The first casualty when war comes is truth.

US SENATOR HIRAM JOHNSON, 1917

This is the point to which censorship has reduced usthat the German official accounts are far truer than our own.

C.E.W. BEAN, DIARY, 26 SEPTEMBER 1915

S trict military censorship was responsible for the withdrawal from bookshops of the second edition of Sydney Lochs The Straits Impregnable , a candid book about his war experiences described in a review at the time of its publication as the best written on Gallipoli.

While serving at Gallipoli, Sydney Loch, a former grazier from Gippsland, Victoria, had kept a detailed war journal, which he took with him when he was evacuated from Gallipoli on a hospital ship. Crippled by polyneuritis and wracked by typhoid fever, Sydney had been on the danger list in hospital at Alexandria, Egypt, before being shipped back to Melbourne. His long convalescence provided him with an opportunity to turn his war journal into a publishable narrative.

Unlike most narratives by Gallipoli veterans, the typescript of Sydney Lochs story was never submitted to military censors, as laid down in the wartime Rules for Censors, published in 1915.

Sydneys literary agent, Harry Champion of Collins Street, Melbourne, put up half the money to publish Sydneys war journal. Champion considered it important that people sheltered from the grim reality of the Gallipoli campaign understood what the situation was really like.

To avoid censorship, the publisher proposed to call The Straits Impregnable a novel rather than a war memoir. He was aware that by publishing Sydney Lochs story as fact rather than fiction he could be prosecuted for contravening the War Precautions Act, which forbade distributing material likely to discourage men from enlisting in the Australian Imperial Force, which badly need new recruits.

In July 1916, about half a year after the Anzacs had been evacuated from Gallipoli, the first edition of The Straits Impregnable was published in Melbourne under the authors pen name of Sydney de Loghe. Although The Straits Impregnable was published as fiction, most of its readers would have perceived Sydneys vivid description of the horrendous conditions at Gallipoli as the truth, which had long been withheld from them by strict censorship. As a result, the book soon became a bestseller.

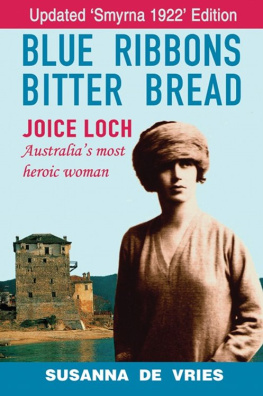

Sydney Lochs novel received excellent reviews in several papers. Miss Joice NanKivell, book reviewer for a Melbourne paper, regarded it as the best book yet written on Gallipoli and asked to meet the author.

The first edition of The Straits Impregnable sold out within a few months, so Harry Champion was keen to publish a second one. To drive home the point that the horrors observed in the first edition actually happened, and keen to do whatever he could to reduce the chances of the forthcoming conscription referendum succeeding, Champion rashly added a preliminary note to the second edition: This book, written in Australia, Egypt and Gallipoli, is true. He placed the note facing the first page, where no reader could miss it. The second edition, with the note and a blue cover rather than the first editions red one, was published towards the end of 1916.

The preliminary note in the second edition of The Straits Impregnable was brought to the attention of the military censor for Victoria, Major L.F. Armstrong. He demanded that the book be withdrawn from all bookshops and threatened Champions small publishing houseand his authorwith legal action for breaking the War Precautions Act. Major Armstrong was a former barrister, so Harry Champion asked his lawyer friend Maurice Blackburn to negotiate with the censors office in an attempt to avoid prosecution.

The lawyers proposed a compromise: under his pen name of Sydney de Loghe, Sydney would write a series of newspaper articles about the danger Britain now faced and how those of British extraction should help defend it, and Harry Champion would publish Sydney de Loghes collected articles in a pamphlet at a later date.

By now it was apparent that the war in France was going very badly indeed. There were fears that German troops might defeat the Allies, and could even invade Britain. The awful prospect of a German invasion of Britain, the country where Sydney Lochs parents lived, is likely to have prompted him to accept the compromise proposed by the censor. To settle the matter without further complications although by now Sydney had very mixed feelings about war and the after-effects. Sydney wrote the required articles. In 1918, shortly before the armistice, Champion published them in a pamphlet under the title One Crowded Hour, A Call to Arms .

The Australian novelist Miles Franklin, who had left America for London in October 1915, received a review copy of The Straits Impregnable from Harry Champion. As a friend of Harrys wife, she was entrusted with the secret that the authors real name was Sydney Loch and that he had served as a gunner and brigade runner at Gallipoli.

According to Miles Franklin and literary critic H.M. Green, The Straits Impregnable was a work of literary merit, as well as the best account of the courage and endurance shown by the Anzacs, and a vividly written history of the Gallipoli campaign. Miles found the book lively and amusing, with poetic descriptions of the landscape of Gallipoli.

Miles Franklin felt that Sydneys book should be published in Britain so the British would understand the psychology of the Anzac troops and the difficulties they had faced so bravely and without complaint during the Gallipoli campaign. Consequently, she took steps to sell the British rights to The Straits Impregnable to Sir John Murray for his London publishing house. In the British edition, which was published in 1917, the note about the book being a true story was repeated. Although the war had just started to go very badly for the Allies, there is no indication that the British censor objected to the book.

Through the publication of the British edition of the book, Sir John Murray and Sydney Loch began what was to be a long friendship. Later this friendship extended to Sydneys Queensland-born wife, journalist and author Joice NanKivell. Several of the Lochs subsequent books, set in war-torn countries where the Lochs were working in refugee camps funded by the Society of Friends, would be published by Murray over the next two decades. During that time Sydney and Joice Loch would become two of the most remarkable members of the postwar generation, for their outstanding work with refugees.

The censorship provisions laid down in the Commonwealth governments War Precautions Act of 1914 (amended in 1915) were the equivalent of todays Official Secrets Act. At Gallipoli the War Precautions Act was strictly implemented, on orders from General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander-in-Chief of the Dardanelles campaign, and his subordinate, General Braithwaite.

Next page